In a program note to one of the current productions of his plays at 59E59 Theaters, British playwright Alan Ayckbourn acknowledges a debt to J.B. Priestley. Priestley’s inventive splintering of time in plays like Dangerous Corner, Ayckbourn writes, has inspired him. Thus the simple time frame of Ayckbourn's early masterpiece Absurd Person Singular (1975), which charted the changing fortunes of its six characters over three Christmases, led eventually to Communicating Doors (1994), where stepping through a door in a hotel suite takes a character back 20 years. In 1999 came the tour de force House and Garden, which have to be played in adjacent theaters simultaneously, so that characters from House exit into Garden, and vice versa, and actors work in two plays in one evening.

Ayckbourn also plays with time in his newest work, Arrivals & Departures, a comedy that may rival Woman in Mind (1985) and Wildest Dreams (1991) as one of his darkest.

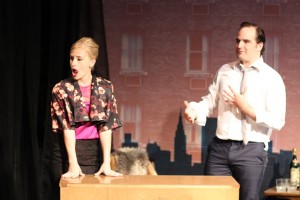

At a railway station, Quentin (Bill Champion), the director of a police task force, is planning to intercept a seemingly slippery and dangerous criminal, “codename Cerastes.” Quentin is directing a squad of agents in their disguises, and things are going egregiously wrong. One “father” holds his “baby” by the feet; a female “tourist” mangles a would-be Norwegian accent. As Quentin notes, “The closest she’s ever been to Norway is Botswana.” In short order, though, Quentin has other worries. A young female police officer, Ez (Elizabeth Boag), who is about to be discharged from the force, is assigned to his unit to protect the only known eyewitness who can identify Cerastes, a bluff old Yorkshireman named Barry (Kim Wall), who arrives by helicopter.

The story then journeys in flashbacks to Ez's childhood and adolescence, as scenes alternate between her recollections and the inane attempts of Barry to talk to her. Her father dies in military combat, and she develops a deep-seated hostility toward men, feeling abandonment. Eventually she joins the police force. Even though she shrinks at anyone's touch, she has a romance with a man named Rob, but at her insistence there is no sex. At 23, she is constantly morose and, unfortunately, one finds it difficult to sympathize with her. Boag is suitably dour, and suggests that Ez has unresolved daddy issues.

Act II is when Ayckbourn pulls off one of his expected theatrical tricks: the action of the play starts over (with subtle adjustments), and this time we follow Barry's early life — marriage, children, overbearing in-laws — through flashbacks. A man who seemed eccentric, charming, and harmless turns out to be as deeply unhappy as Ez. In what is surely one of the bleakest endings of any Ayckbourn play — and it feels like a forced plot twist — Ez and Barry finally find a connection.

Well-known Ayckbourn themes are reworked here. Among them are the unseen misery of people who seem content and confident, and the incompetence and pettiness of people who hold authority (echoing 2011’s Neighbourhood Watch). The dramatist's observation of the British middle class is as astute as ever.

Although Ayckbourn intends Arrivals & Departures to be in a more serious vein, fans who are used to his generally comic spirit will find this atmosphere predominantly tragic. That’s the playwright’s prerogative, of course, but the comedy and tragedy here jostle each other uneasily. The harshness of Ez’s character, though it abates in the second act, when Barry is the focus, is off-putting. A confrontation between Ez and Rob’s parents touches abruptly on British class friction, and the final portrait of Rob that emerges doesn’t square with the patient, decent character that Richard Stacey has created.

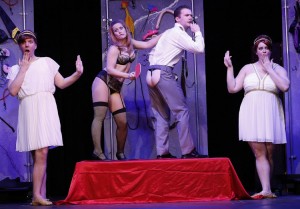

Nonetheless, under the author’s direction, the actors do a fine job bringing this thorny anomaly to life. As part of the Brits Off-Broadway festival, 59E59 is offering a generous helping of Ayckbourn (he has written 78 plays), with visiting productions from the playwright’s own Stephen Joseph Theatre in Scarborough: a revival of his 1992 play, Time of My Life, is also being presented, and though it, too, has a serious side, a third bill contains two one-acts under the umbrella title Farcicals.

Arrivals & Departures, Farcicals and Time of My Life play in repertory through June 29 with marathons on Sundays. For tickets and times, visit www.59e59.org.