Classic Stage Company’s production of Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, directed by Andrei Belgrader, doesn’t do away with Marlowe’s mighty line, but his pioneering iambic pentameter has a hard time keeping up with a good deal of lowbrow tomfoolery inserted by Belgrader and his co-adaptor, David Bridel. To be fair, Marlowe larded his play with comic relief, but the CSC production often strains for humorous effect. Early on, when two necromancers visit Faustus, they speak in silly voices for no apparent reason, one of them sounding like a hoarse Munchkin.

The comedy helps leaven the well-known story of death and damnation for the medieval scholar with encyclopedic knowledge who seeks omnipotence as well. Besides Marlowe’s play, its most notable appearances are in operas by Gounod and Busoni and in a novel by Thomas Mann (the last is not easy reading).

By selling his soul to Beelzebub, Faustus gains the service of Mephistopheles for 24 years, but he fritters away all the advantages he has with childish nonsense. He tweaks the Pope and European rulers; he summons long-dead historical figures (including Helen of Troy, “the face that launched a thousand ships,” in Marlowe’s phrase); and has himself a lot of sexual fun. Initially, Faust demands that Mephistopheles find him a beautiful wife, but Mephistopheles tells him that marriage is a sacrament of God, and because Faustus has renounced God, he must be content with concubines. That’s apparently not a problem.

Bridel and Belgrader have understandably changed a great deal. They have cut whole passages skillfully, dropping many references to classical myths and characters and adding plenty of business that's not in the original, including audience interactivity that’s surely more close-up than Elizabethan actors ever got to their spectators. The changes get down to the nitty-gritty, too, as the adapters substitute individual words for ones they deem too obscure for a modern audience, and update archaic locutions. Thus Marlowe’s

Faustus, begin thine incantations

And try if devils will obey thy hest

Seeing thou hast pray’d and sacrific’d to them.

is streamlined to:

Faustus, begin your incantations

And see if devils will obey your will

Once you have prayed and sacrificed to them.

The reworking is extensive, and only occasionally puzzling. Surely Marlowe’s “The framing of this circle on the ground/Brings thunder, whirlwinds, storm and lightning” not only has better iambic scansion than “The framing of this circle on the ground/Brings whirlwinds, tempests, thunder, and lightning,” but “storm” is also a word more commonly used than “tempest.”

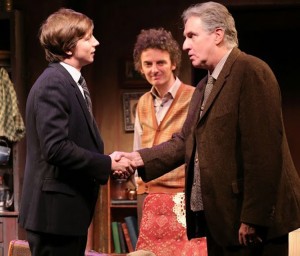

As Faustus, Chris Noth handles the verse with clarity and intelligence, and he shows a troubled, ambitious, scornful spirit. But Faustus’s philosophical musings cannot sustain one’s interest entirely, so besides comedy, Marlowe includes pageantry (the Pope, an emperor, a selection of demons and phantoms) for the eyes. The pageantry here is pretty thin, but Bridel and Belgrader embrace the secondary plots more than that of Faustus, and the imbalance is noticeable. It’s present in the underlings enlisted by Faustus’s own servant, Wagner, who doubles as the Chorus: Lucas Caleb Rooney’s strapping Robin, who swipes Faustus’s books of magic with a barking, raffish energy to teach himself the dark arts; and then Robin’s own protégé, Ken Cheeseman’s idiot peasant Dick, who gives rise to plenty of punning. “I shall be the Devil’s Dick,” he cries exultantly, in just one of a series of Dick jokes that bump vulgarly against the higher-brow issues involving God and the fall of man.

Zach Grenier brings a weary glumness to Mephistopheles, the devil who remembers longingly the joys of Paradise but who has adapted to the reality that he’ll never know them again. His glances at Faustus show what a fool he thinks the doctor is, and he seems the real tragic figure. Belgrader also includes a good deal of audience participation, as Mephistopheles sniffs out sinners at close quarters, and there is one clever twist as the Seven Deadly Sins are presented, although their forming a kick line as they whinny out a song is just directorial froufrou.

Still, if bumblers and hijinks diminish the tragic effect and Marlowe’s transporting poetry, the production retains integrity. And if Faustus’s final descent to the fiery pit isn’t likely to bring forth any catharsis, that’s partly because Faustus concerns himself with trifling pranks. It's too bad, though, that Belgrader couldn't imbue this production with a bit more gravitas.

Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus plays at Classic Stage Company (136 E. 13th St. between 3rd and 4th Aves.) through July 12. Evening performances are at 7 p.m. on Tuesday-Thursday and 8 p.m. on Friday and Saturday. Matinees are at 3 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. Tickets may be obtained by calling 212- 352-3101 or visiting www.classicstage.org.