The world premiere of Rising Circle Theater Collective’s production This Time, written by Sevan K. Greene and adapted in part from Amal Meguid's memoir Not So Long Ago, is an extraordinary example of juggling multiple timelines with exacting deftness. The storylines weave in and through one another, much like a memory comes in and out of consciousness. The underlying theme? A life of no regrets.

Delphi Harrington is brilliant as Amal, an overbearing, ethnic mother, one who professes to want only the best for her child but has a distinct opinion about everything. She exhibits the mannerisms and inflections of an older, well-traveled woman. Salma Shaw as her divorced daughter, Janine, comes to her aid when she has broken her arm bringing her home with her to recover. Janine is attempting to pack up her own home to put it on the market, downsize, and restart her life.

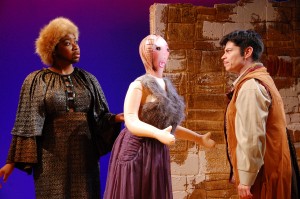

In flashbacks to 30 years earlier, the younger Amal, played by Rendah Heywood, meets a charming man-about-town, Nick (Seth Moore), at a party in Cairo. Heywood is cocktail-party elegant as she employs aloofness to counter Nick’s advances.

Nick: “Alone?”

Amal: “Married.”

Nick: “Happily?”

Amal: “Married.”

Nick: “Unfortunate.”

She eventually succumbs, wanting to be free of the oppression she feels in Egypt, yet comes to struggle with Nick’s life choices.

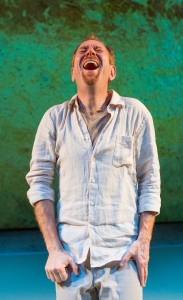

A scene near the end has each of the four main actors taking a seat at the dining table, eating and arguing across one another, and at times sharing the same line. The actors’ timing is impeccable in this charged interaction, demonstrating a fluidity of movement between decades that brings the play alive.

Amal: “You’re leaving.

Younger Amal: “I’m leaving.”

Nick: “You could use a break.”

Younger Amal: “I said I’m leaving.” Amal: “I said you’re leaving.”

Nick: “Good.” Janine: “Good.”

Younger Amal: “No, Nick, I want a divorce.”

Amal: “And what about me?”

The direction by Kareem Fahmy keeps the action moving smoothly between decades. At times Amal remains onstage, as an observer, while her younger self and Nick interact. In one touching scene she “feels” Nick holding and whispering to her, as if she were the younger Amal, with the younger Amal standing just to the side, also experiencing Nick.

Ahmad Maksoud dexterously plays multiple characters, including an Egyptian shopkeeper; Amal’s son, Hatem; and Janine’s younger love interest, Tom. Together, the cast brings the story of This Time to life using English, Arabic, and French. Their accents are delicious.

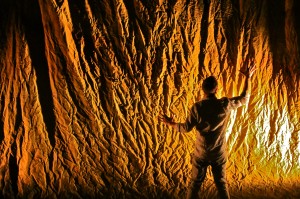

Designer David Esler’s set of a house in Toronto circa 1990s transitions easily to an apartment in Cairo roughly 30 years earlier. The Toronto house is split-level with a dining room, kitchen doorway, and entry hall, stairs to a second floor, and a sunken living room. Employing five panels, scenic backgrounds transition from the skyline of Egypt to the coast of Rhode Island and winter in Toronto, gently helping to delineate location and time.

The settings are enhanced by the sound design of Mark van Hare, from the opening sound of Edith Piaf modulating from house music to the distinct sounds of a phonograph playing in the living room. The costumes designed by Sarafina Bush are bold and smart.

Two quibbles. First, although the lighting by Scott Bolman is generally quite effective, it sometimes results in actors’ obscuring one another in shadow. It may be the result of a lack of technical rehearsal, but it can be distracting. Second, the end of the play is abrupt. The ever-giving Janine, whose children have grown and whose husband has gone, is at odds with her purpose in the world. “This is supposed to be my time,” she cries. “What the hell do I need?” The end is meant to feel generational, almost as if passing a baton from a strong woman to another strong woman; Nick’s presence is a distraction.

Too often, it seems, modern playwrights are challenged with creating a strong enough arc to engage an audience for two acts, instead relying on one long act. That is not the case with This Time. Greene’s storytelling is compelling and fresh, with engaging narratives. Piaf may have said it best, though: “As you leave, I can say, no, we will have no regrets.”

This Time is playing through May 21 at The Sheen Center’s Black Box Theater (18 Bleecker St. between Mott and Elizabeth streets). B/D/F/M trains to Broadway/Lafayette stop. For more information and tickets, contact The Sheen Center or visit sheencenter.org.