The WorkShop Theater Company’s production of The Winter’s Tale is a very traditional staging of William Shakespeare’s play, which emphasizes the beauty of the words and the great characters that define the Elizabethan bard. In the play, Polixenes, the ruler of Bohemia, has been a guest for nine months at the court of Leontes, the king of Sicilia. He is about to leave, yet Leontes’s wife, Hermione, lovingly persuades Polixenes to postpone his departure. That is the moment when jealousy blinds the Sicilian king. He subsequently accuses his pregnant wife of being unfaithful and imprisons her. Notwithstanding Paulina’s (a noblewoman loyal to the queen) defense of his wife’s innocence, Hermione gives birth to a girl in prison. Only after their young son and Hermione die of grief and the newborn has been abandoned in the dangerous Bohemian woods under his own orders, does Leontes realize the error of his ways. This is only the first half of a play whose surprising turns include a confirmation of innocence by the Oracle at Delphi, a fatal bear attack, and a statue that suddenly comes to life.

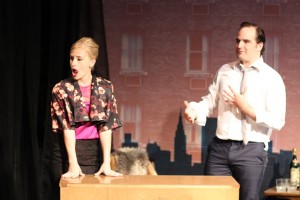

In the staging, the action is divided between two countries, Sicilia and Bohemia. Sicilia is portrayed as a barren and cold space. The walls are covered by curtains of black plastic bags and the nobility is dressed in dark suits. Leontes himself wears a black military uniform, which brings to mind the fascist dictators of the mid-20th century. Ethan Cadoff does a great job of portraying the frigidity of the character, whose only humanity is exposed with his jealous outbursts. Laurie Schroeder’s performance as Hermione exudes a flirtatious candor that somewhat explains her husband’s reaction. The production does a great job in staging the tragic first half of the play, the winter part of the tale referenced in the title.

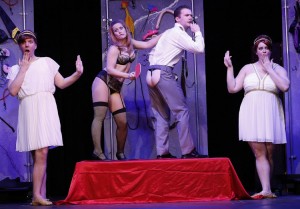

In the second half of the play, the action moves to Bohemia 16 years after the incidents in Sicilia. At this point, the play is taken over by the light, humor and festivities of spring, whose overt sexuality follows the spirit of the pagan fertility rituals. The plastic bags slide open to uncover the mountains and blue skies of Bohemia. Michael Minahan’s set design marks in a simple and effective way the change in space and tone from the first half. Autolycus, the comic rogue, further establishes the merriment that distinguishes Bohemia. Robert Meksin plays the character with delicious abandon, singing and picking the pockets of the bumpkin clown.

Ryan Lee’s direction successfully portrays the Sicilian barrenness that opposes Bohemia’s chaotic innocence.

Angela Harner’s costumes also distinguish each space. The Sicilian dark suits are discarded for the colorful Bohemian garbs that allude to 1960s trends. On one hand, Polixenes’s attire brings to mind the Eastern influence on Western fashion, while on the other hand Autolycus’s clothes represent the errant hippie. Although some of the Bohemian costumes are too ridiculous and lack a general cohesiveness, they create an interesting effect since the same actors who wore the repressive and uniform suits during the first half, now appear as Bohemian revelers wearing neon colored see-throughs, heavy makeup and shiny pants.

The whole cast does a marvelous job of juggling the two opposites of Sicilia and Bohemia. While Annalisa Loeffler’s Paulina fervently defends Hermione’s virtue while constrained in a gray skirt suit in Sicilia, her Bohemian Dorcas dons a feathered boa and red sunglasses. Along the same lines, Jacob Callie Moore plays the Clown with comedic energy and hence is almost unrecognizable as the much more serious Sicilian Dion. This production of The Winter’s Tale turns the bleakness of a tragic winter into the vibrant sensuality of spring.

The Winter’s Tale runs through March 15 at the WorkShop Theater Company's Main Stage (312 West 36th St., 4th Fl.). General tickets are $18; $15 for students and seniors. For tickets, call 866-811-4111 or visit www.workshoptheater.org.