In the opening moments of Theater for a New Audience’s The Tragedy of Julius Caesar, Metellus Cimber (Ted Deasy), one of the conspirators against Caesar, confronts a “mechanical,” or ordinary citizen, who is out on the street loudly celebrating the festival of Lupercal. Metellus ends up putting a chokehold on the man and then tossing him to the ground. The violent energy doesn’t let up for the next two hours and 40 minutes of a production that, at moments, is clear and invigorating, but at others sacrifices subtlety for movement and spectacle.

Perp

In telling the story of an innocent young man wrongly convicted of a brutal murder, Lee Brock’s highly watchable production of Lyle Kessler’s Perp becomes a battle between good and evil. Its colorful characters challenge black-and-white assumptions, which in turn gives rise to universal questions about which side of this dichotomy they are on. But perhaps the most noteworthy aspect of the play is the professional debut of Ali Arkane in the lead role. Arkane’s quirky portrayal of the protagonist Douglass is endearing through and through. With Douglass as the criminal center stage, Perp is one of the most serene crime dramas ever.

Smart Blonde

Willy Holtzman calls his pocket-size play about Judy Holliday Smart Blonde. Not a bad title, considering Holliday’s reportedly high IQ and her early success, on stage and screen, as Billie Dawn, the seemingly dumb, actually discerning protagonist of Garson Kanin’s 1946 smash-hit comedy Born Yesterday.

The Mother

Florian Zeller’s play, The Mother, is subtitled “a black farce.” If that conjures images of slamming doors and maids running around frantically in their underwear, forget it. The frenzied activity in Trip Cullman’s production is almost entirely provided by the great French actress Isabelle Huppert, and although she strips down to a slip and garters at one point to put on a sexy red dress, it’s not at all lubricious or funny.

Superhero

Superheroes haven’t had an easy time of it in musicals. It’s a Bird … It’s a Plane … It’s Superman opened in 1966 to critical praise but public indifference, and then there was that little show about Spider-Man some seasons back. Add to this unlucky list Superhero at Second Stage, which at least invents its own superheroes rather than sullying the reputations of beloved ones. Further, it’s beautifully produced, assembled by experienced hands (book, John Logan; music and lyrics, Tom Kitt), and possessing several good songs. The trouble is, Superhero isn’t so much written as programmed.

Surely Goodness and Mercy

Grace, blessings, and charity can come from the most unlikely sources and individuals. This is the central premise of Chisa Hutchinson’s Surely Goodness and Mercy, in which a precocious 12-year-old boy and a cantankerous school lunch lady are a pair of unlikely saviors. Set in Newark, N.J., the play shows that amid the grit and grime of urban life, simple acts of benevolence can have reverberating and profound effects.

A Jewish Joke

A Jewish Joke is a one-man show about partnerships, but that is just one of its several paradoxes. The play explores Jewish comedy, though from the serious viewpoint of its effect during the era of the Hollywood blacklist, when humor could either get a guy out of a jam, or reinforce anti-Semitic stereotypes. Many old jokes are told during the 90-minute production; however, they are delivered with such odd undertones that it is impossible to tell whether director David Ellenstein was hoping for legit laughter or uncomfortable sighs from the vintage zingers that are rife with sexism and prejudice. And Joke is a play about writing which, when it falters, does so because the script is, at times, contrived or repetitious. When it succeeds, it does so because Phil Johnson, of San Diego’s Roustabouts Theatre Company, so fully inhabits his role that his character’s stressed-out persona transcends the page.

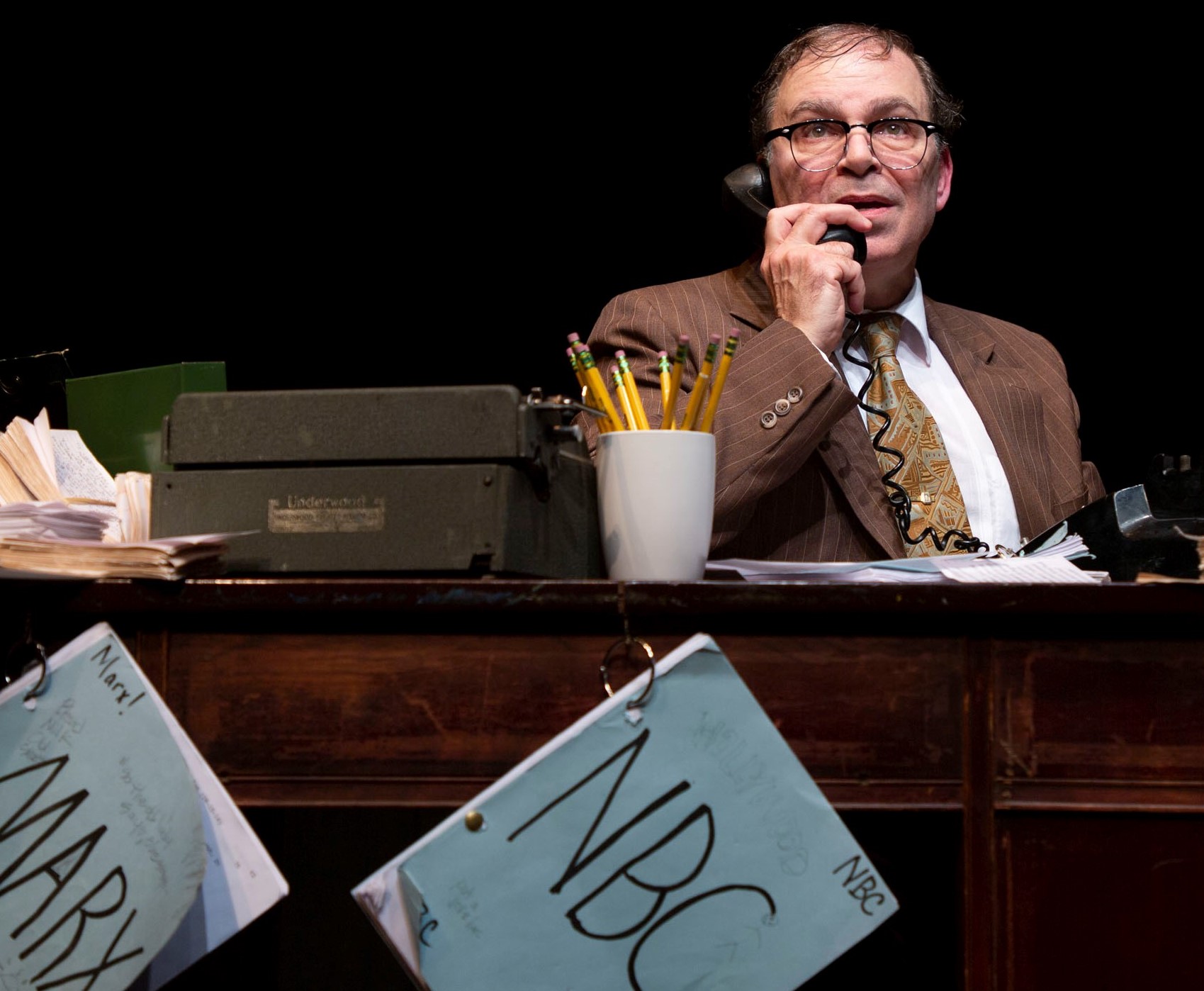

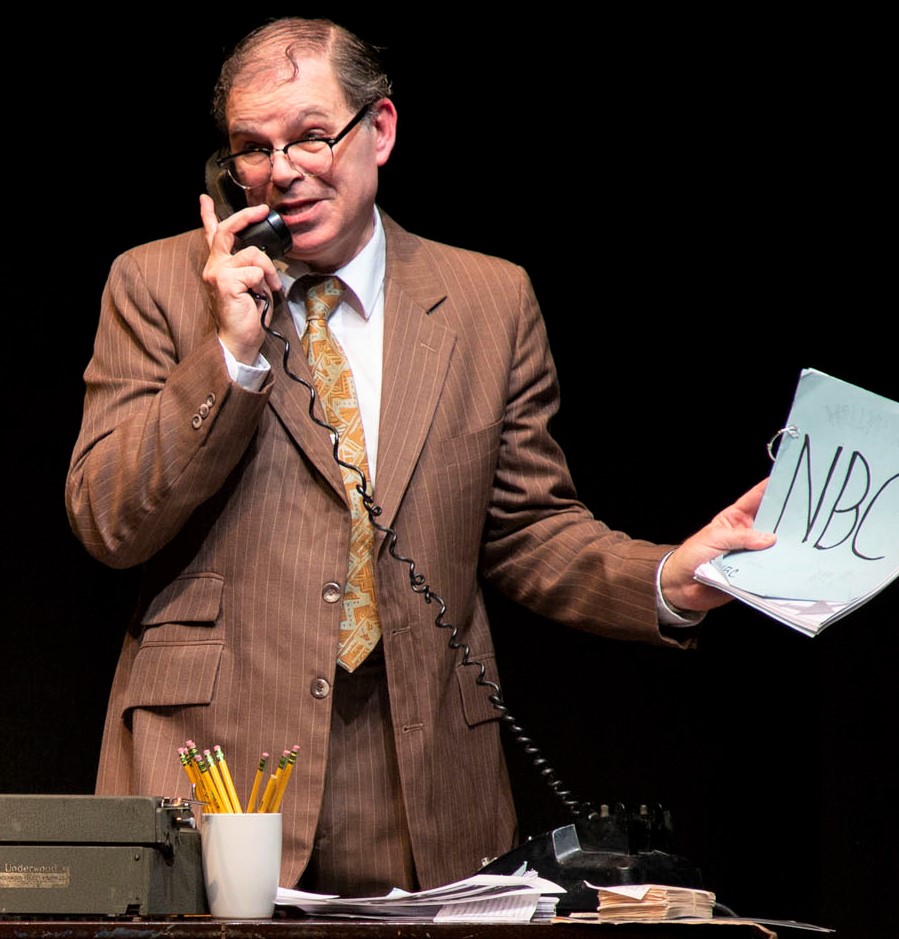

Phil Johnson as Bernie Lutz in A Jewish Joke, written by Johnson and Marni Freedman.

Johnson portrays Bernie Lutz, a film writer for MGM Studios in its mid-20th-century heyday. Though successful at his craft, he looks the worse for wear. His sad brown suit is wrinkled, his tie atrocious, his eyeglasses cheap, and his limp comb-over barely covers his scalp. He would be considered Kafkaesque, except that on this particular morning he finds he has been transformed into, not a cockroach, but a commie. His name, along with that of his lifelong friend and writing partner, Morris Frumsky, have turned up in Red Channels, the right-wing publication that, in 1950, accused scores of entertainers and journalists of having ties to the Communist Party (Real-life names cited by Red Channels ran the artistic gamut from Orson Welles to Dorothy Parker to Leonard Bernstein.).

It seems Morris had recently taken Bernie to a soirée that was more than just the cocktail-weenie extravaganza Bernie thought it to be. The fact that Morris is nowhere to be found as the play begins, despite the fact that their latest flick, The Big Casbah, is set to premiere that very evening, telegraphs all we need to know about Bernie’s impending doom. But Johnson, who co-wrote the piece with Marni Freedman, walks us through Bernie’s very bad day nonetheless. First, it turns out that the government had sent him a warning letter regarding the “important work of investigators under Senator Joseph McCarthy,” but he conveniently had torn it into three pieces without bothering to read it, allowing him to now build tension by slowly finding each section amid the piles of crumpled papers strewn about his bungalow. Then his colleagues begin disassociating. Danny Kaye shows him the door. Louis B. Mayer has no time for him. And when Harpo Marx gives him the silent treatment, he reaches a crisis point: testify against Morris to clear his own name, or protect his pal and risk sacrificing his career.

Bernie treads the fine line between comedy and tragedy. Photographs by Clay Anderson.

Without other characters in the room to play against, Bernie frequently turns to the audience and tells one of the many off-color gags he has collected on index cards. Most are groaners and, whether meant to be awful or not, they do keep the audience from becoming too emotionally caught up in Bernie’s dilemma. It’s the old “alienation effect,” a technique pioneered by another member of the Hollywood blacklist, Bertolt Brecht.

Bernie also has framed pictures of his wife and his parents with which to interact. But mostly, he is on the phone. Indeed, the plot revelations are entirely dependent on the seemingly endless number of calls that Bernie makes and receives. The playwrights employ a couple of devices to minimize the drudgery. Rather than repeatedly having to dial the rotary phone, Bernie has an unseen secretary place his calls. Somehow, she is able to do so with lightning speed, adding a surreal aspect to the evening. And Bernie answers the phone each time with a different one-liner (“Bernie’s Yacht Club”). None are particularly funny, but it beats enduring a hellacious string of hellos.

Production supervisor/designer Aaron Rumley provides a desk for Bernie to work behind, and I will just assume that its drawers are full. Why else install hooks across the front of it and glaringly hang from them the scripts that Bernie risks forfeiting? Regardless, Johnson, who has been touring and perfecting this role since 2016, when the show won Best Drama at the United Solo Fest NYC, makes it work, taking his character’s motto to heart: “When there is no mensch, be the mensch.”

A Jewish Joke, by Marni Freedman and Phil Johnson, runs through March 31 at The Lion Theater (410 W. 42nd St.). Evening performances are at 8 p.m. Wednesdays through Saturdays; matinees are at 3 p.m. Sundays. For tickets, call Telecharge at (212) 239-6200 or visit ajewishjoke.com.

Marys Seacole

Jackie Sibblies Drury is not content to let audiences just watch her plays; she wants to make them conscious of how and why they are watching. In Fairview, her 2018 breakout, this meant disrupting a black family sitcom with tone-deaf white voices. For Drury, the mundane is anything but; it’s in banal, everyday interactions that society’s fault lines become most clearly visible, if we know how to see them.

Actually, We’re F**ked

Playwright Matt Williams created the TV series Roseanne, co-created the TV series Home Improvement, and was a writer on The Cosby Show, which is to say that the man knows a little something about domestic comedies in which hard-working parents love and nurture their large families. In his new play, Actually, We’re F**ked, he attempts to go in a different direction, exploring whether two young couples who are barely holding their marriages together can stop fretting, navel-gazing, and betraying each other long enough to have, or even want, a ch**d.

Daddy

Psychosexual hang-ups were at the center of Jeremy O. Harris’s Slave Play earlier this season, and they form an important part of Daddy, his newest work. Daddy, too, has an interracial gay relationship at its core, but this time Harris’s interests encompass homophobia, ageism, materialism, parental strife, fundamentalist Christianity, and the philosophy of art.

Hurricane Diane

Hurricane Diane packs a lot into its 90-minute running time. It’s the type of idea-driven play that in lesser hands might become more academic journal article than piece of theater, but writer Madeleine George and director Leigh Silverman have crafted the evening with a deceptively light touch. Not since Dr. Strangelove has humanity’s inevitable annihilation been such a good time.

We Are the Tigers

We Are the Tigers, which punningly describes itself as “a killer new musical,” is a whodunit that explores the trajectory of a group of teenage girls who couldn’t be more different. The girls are part of a cheerleading team called the Tigers, but are dogged by an epic stumble in the last game which went viral and left them the laughingstock of their high school community. This year, they’re determined to make a comeback. In the course of an evening, two cheerleaders are bumped off and another set up, but can the motive really be just to restore their reputation?

Twelfth Night

The twisted identities and raucous antics of William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night have delighted audiences for centuries—and a new production is showing why. Directed by Lynnea Benson, Frog and Peach Theatre Company’s Twelfth Night offers an enjoyably accessible take on the Bard’s famed tale.

Good Friday

The New York premiere of Kristiana Rae Colón’s new play Good Friday could not have come at a more imperative time in our culture. In an age when baby boomers’ once-earnest activism (the women’s movement of the 1970s) has been replaced by millennials’ equally well-meaning, but less effective “slacktivism” (#MeToo, #YesAllWomen), what does it mean in this day and age to call oneself a feminist? And what happens when women are forced to confront their belief systems, however different, just as a crisis occurs?

The Price of Thomas Scott

Over the next few months, the estimable Mint Theater, committed to rediscovering lost theatrical treasures, is producing three works by English playwright Elizabeth Baker. The first is The Price of Thomas Scott, a 1913 comedy-drama that features a top-notch ensemble of New York actors in a handsomely designed staging directed by Jonathan Bank.

State of the Union

In the middle of the last century, Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse—producers, publicists, and prolific playwrights—were leading lights in the American entertainment industry. They are now remembered for writing Life with Father, the longest-running nonmusical play in Broadway history, and the libretto of The Sound of Music. Their 1945 hit State of the Union won the Pulitzer Prize and became a Frank Capra movie starring Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn. That play is typical of the witty comedies with serious-minded underpinnings that Broadway audiences relished during World War II and after.

The Shadow of a Gunman

On Aug. 14, 1924, after a third night of sold-out houses at the Abbey Theater in Dublin, inveterate Irish playgoer Joseph Holloway noted in his diary: “The Shadow of a Gunman [has] been staged for three nights with the usual result—that crowds had to be turned away each performance. . . . Certainly [Sean O’Casey] has written the two most popular plays ever seen at the Abbey, and they both are backgrounded by the terrible times we have just passed through, but his characters are so true to life and humorous that all swallow the bitter pill of fact that underlies both pieces.”

Switzerland

The challenging economics of New York theater makes two-actor plays a holy grail for Off-Broadway producers. Among the numerous two-handers of the past three or four theater seasons, none has had a more arresting first act than Joanna Murray-Smith’s Switzerland. Set in an Alpine aerie, with Cold War elegance courtesy of scenic designer James J. Fenton, Switzerland depicts a showdown between Patricia Highsmith (Patricia J. Scott), author of Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley, and a man she has just met named Edward Ridgeway (Daniel Petzold).

The Trial of the Catonsville Nine

The Trial of the Catonsville Nine, in revival at the Abrons Arts Center, is about the Catholic activists who burned 378 draft records with napalm in Catonsville, Md., in 1968, because “pouring napalm on pieces of paper is preferable to pouring napalm on human beings.” Its author, the Rev. Daniel Berrigan, was a member of the Nine and a lifetime antiwar activist. In his play, Berrigan edits and interweaves excerpts of the trial to build arguments against the Vietnam War and U.S. militarism.

David Huynh and Mia Katigbak in The Trial of the Catonsville Nine. Top: Huynh and Eunic Wong.

Over the course of the trial, the group’s members attempted to draw connections between issues, only to be told, “We are not trying that case.” Berrigan cannily demonstrates how all social and political issues are linked, no matter how much the powers that be might wish it otherwise. There is little self-awareness in this hyperbolic play (which, for example, draws parallels between the U.S., with its involvement in Vietnam, and Nazi Germany) but plenty of fervent belief in its own virtue.

Yet the play engages in its own bit of division by almost entirely removing the point of view of the war’s victims in order to celebrate antiwar activists. With a cast of only Asian-American actors, this production, directed by Transport Group artistic director (and Catonsville native) Jack Cummings III and co-produced by the National Asian American Theatre Company, provides a small corrective to the play’s narrow viewpoint.

Actors David Huynh, Mia Katigbak, and Eunice Wong are generous performers. Their well-rehearsed connectivity overcomes Cummings’s hyperactive staging, which seats the audience on spartan wooden pews around the perimeter of the Abrons stage (the theater’s actual seats are unused) and often pulls the actors to opposite corners of the set to bring them nearer to the viewers.

The performers shift characters and locales quickly to accommodate the verbatim format, as witnesses take turns testifying. Unfortunately, these shifts happen so often that each role is given only the most superficial characterization; there’s no time for the internal tensions and oppositions that make a character interesting. Katigbak is best able to find colors in the characters she plays, while Huynh has been directed to deliver every line at a relentlessly humorous, overbearing pitch.

In this he reflects the production as a whole. From R. Lee Kennedy’s blood-red lights, which bathe the space as the actors enter the theater to the accompaniment of Barry McGuire’s 1960s protest classic “Eve of Destruction,” to sound designer Fan Zhang’s Brian Eno–lite score and omnipresent low rumbles, shaking the pews, the evening is monochromatically morose. The subject matter is undoubtedly solemn, but by denying the pleasure of activism, the full-body thrill when the match strikes the napalm, The Trial of the Catonsville Nine has made the Vietnam War the one thing it was not and theater the one thing it should never be: boring.

Huynh and Wong. Photographs by Carol Rosegg.

The evening’s best theatrical moment comes near the end of the play, when the stage curtain on one side and the loading door on the other side drop quickly, cutting the audience off from the outside and blinding them with white-hot lights. Setting aside the hypocrisy of a production with so little self-awareness daring to interrogate and implicate its paying audience, the moment at least packs a visceral thrill. Yet the thrill dissolves when the curtain rises at the end to reveal the empty auditorium filled with haze and more blinding white lights, into which the actors disappear as though passing through the pearly gates. The angry protest music of the actors’ entrance becomes the New Age-y strains of DJ Drez’s sitar-heavy “India Dub” of “For What It’s Worth” (you know: “Stop, hey, what’s that sound, everybody look what’s going down”), and a benign evening honoring activists blossoms into full-blown, tone-deaf hero worship.

Berrigan’s fawning platitude is little better than the propaganda that implores Americans to honor “the troops.” The truth is, we don’t need any play, ever, and it’s past time that productions like The Trial of the Catonsville Nine, which mistake gravitas for gravity and crocodile tears for emotional heft, stop taking that fact for granted.

The Transport Group and the National Asian American Theatre Company’s production of The Trial of the Catonsville Nine plays through Feb. 23 at Abrons Arts Center (466 Grand St.). Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays; matinees are at 3 p.m. Sundays. For tickets and information, call OvationTix at (866) 811-4111 or visit transportgroup.org.

The Waiting Game

Last year’s Off-Broadway production of Daniel’s Husband by Michael McKeever focused on a loving gay couple whose lack of a legal document deprived the title character (named Mitch) of the right to determine the care of his spouse, who was stricken with a serious disease. It was easy to sympathize with the principals, whose desire for normal domesticity elicited sympathy. Charles Gershman takes a more daring tack in his new play The Waiting Game: his “hero,” Paolo, is a meth-smoking lodestar of promiscuity.

Paolo’s husband, Sam, has overdosed on heroin and is on life support, brain-dead, although Paolo has since found solace with Tyler, a new boyfriend, who is desperately trying to find a job but is also extricating himself from Paolo’s influence. Gershman deserves credit for taking a darker approach, but the result is puzzling and unsatisfying.

Julian Joseph (left) plays Tyler, and Marc Sinoway plays Paolo in Charles Gershman’s The Waiting Game. Top: Sinoway with Joshua Bouchard as Geoff.

Paolo is more interested in drugs, whether it be a joint or crystal meth. His sex life with Tyler (Julian Joseph) has deteriorated, and Tyler is hanging on in the hope that Paolo may do an about-face and forget Sam. As Tyler points out, “Paolo, you visit like three times in the time that we’re dating. You barely see him in three months…” But Paolo is not thinking straight: he is consumed by the fact that Sam had been having an affair with another man long before his overdose. “All you’ve been saying is that I need to get over Sam,” he tells Tyler. “After ten diff— Ten beautiful years. And the sad thing is I can’t fucking tell much of the time if that’s you being possessive.”

When Paolo meets a man named Geoff at the hospital, he knows that it’s Sam’s new lover. Geoff (Joshua Bouchard), who works in finance, seizes on the chance to meet and talk with Paolo. He wants to persuade Paolo to assign him the conservatorship over Sam’s life because he is, in effect, now the real husband. Paolo, in exchange, demands sex with Geoff. Tyler gets wind of this new twist and, for him, it’s the last straw.

The melodrama is thick, downbeat and contrived. Still, there is something intriguing—although unresolved—in the messages Paolo is receiving on his laptop that he thinks are from the stricken Sam. It’s not his imagination, because Tyler sees them, but it’s also a bit loopy. If it’s not Sam’s spirit, it might be Geoff playing mind games.

There’s little the actors can do to salvage this goulash. There are indications that Paolo hasn’t had it easy in this relationship: he is clearly an emotional mess, riddled with guilt, but Marc Sinoway relies mostly on a sullen pout, broken only occasionally by a smile of faux bonhomie toward Tyler.

Paolo and Tyler share a light moment. Photographs by Carol Rosegg.

The moral center of the play, even more than Joseph’s likable Tyler, is Geoff, the new lover who wants and needs to take care of Sam. Bouchard persuasively embodies decency; his teary-eyed strength stands in contrast to Paolo’s self-destructiveness, and even when he succumbs to sexual blackmail, it’s for Sam’s benefit. (Perhaps it helps, too, that the paleness of Bouchard’s skin gives him an otherworldly, angelic aura, but his magnetism doesn’t depend on that.) Still, even the gay milieu doesn’t enliven the action much.

Director Nathan Wright and his designer, Riw Rakkulchon, have introduced a dose of surrealism into the small black-box space that is as baffling as it is useful. There’s a box marking the perimeter of the playing area, and key props in the plot line: Paolo’s laptop, a pile of New Yorker magazines, Sam’s books of poetry, pipes for crystal meth, and lighters. Each is placed with equal weight, although the cards only come into play in the final moments. Meanwhile, Ibsen Santos, who is Sam, has all the while been hovering upstage, crossing in slow motion, or standing like a ghost figure behind a scrim. On it projection designer Kat Sullivan shows words plucked from the dialogue; then the letters move around to turn them into nonsensical anagrams, but it doesn’t bring one any closer to deducing what Gershman is trying to say.

The Snowy Owl production of The Waiting Game plays through Feb. 23 at 59E59 Theaters (59 E. 59th St.). Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday; matinees are at 2:30 p.m. Sunday. For tickets and information, call (646) 892-7999 or visit 59e59.org.