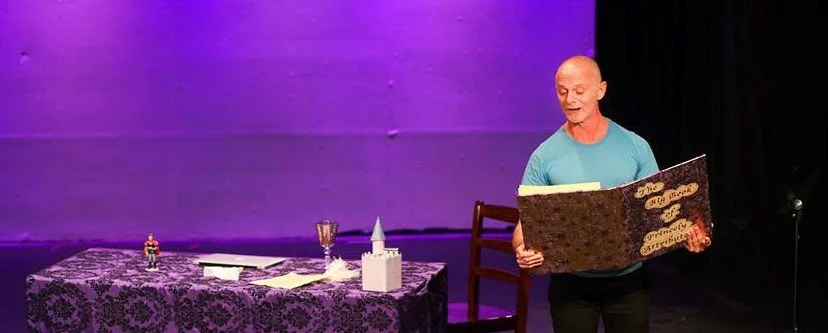

The title of Billy Hipkins’s solo show promises lighthearted fun, and the actor often has a twinkle in his eye as he performs it. However, in spite of the elfin charm of Hipkins himself—a sixtysomething gay man who has worked in theater as a dresser and occasionally an actor—Prince Charming, You’re Late strikes many of the darker notes of a fairy tale by the Grimm brothers.

Yes! Reflections of Molly Bloom

James Joyce’s Ulysses is a brilliant but dense and sometimes inaccessible work. Aedin Moloney’s solo performance in Yes! Reflections of Molly Bloom is adapted from Molly's “Yes!” soliloquy at the end of Joyce’s novel. Co-created by Moloney and acclaimed Irish author Colum McCann, the show is a remarkably ambitious collaboration, a welcome contribution to understanding the complexities of Molly Bloom (wife of Ulysses’ protagonist Leopold “Poldy” Bloom), and a consummate one-woman show.

Jews, God, and History (Not Necessarily in That Order)

Can an atheist serve as a guide to the history, customs, and longevity of the Jewish religion and its adherents? Moreover, how can an atheist recognize that a man who has just died is with God? At first glance, this seems quite absurd. Yet neither for Michael Takiff nor for his audience does it appear to be a problem. Jews, God, and History (Not Necessarily in That Order), Takiff’s one-man show, is a roller-coaster ride through Jewish belief, identity, and practice.

How the Hell Did I Get Here?

For Downtown Abbey aficionados, it is an unlikely stretch to imagine Lesley Nicol as anyone other than the series’ jovial, wise cook, Mrs. Patmore. The leap of imagination that transforms Patmore into a painfully shy, insecure, aspiring and often overlooked actress is a dilemma with which the audience for How the Hell Did I Get Here? must grapple. Ironically, Mrs. Patmore and Ms. Nicol may share a Northern British accent, but that’s where any comparison ends. The former’s “extreme makeover” as fashionable Lesley Nicol is not a makeover at all, but an internal and external transformation from her early childhood. Isn’t that what good acting is all about?

Just for Us

Despite Alex Edelman’s opening caveat that “my comedy barely works if you’re not a Jew from the Upper East Side,” he is one of the rare, masterful stand-up comics who can “cast out” and then successfully “reel back in” a diverse audience. He can take his monologue way off-topic, on a tangent that itself could be a stand-alone show. Although the thrust of Just for Us is his attendance at a white-supremacist gathering, along the way he signs and mimics the distress of a gorilla at Robin Williams’s death (the gorilla really grieved), then quips that Brexit should be called “The Great British Break-Off,” and lovingly, yet mercilessly, spears his family, their Hebrew names, his brother’s Winter Olympics prowess as part of the Israeli skeleton team, and his Orthodox Jewish parents’ finessing of Christmas (including a decorated tree in the garage) to comfort a bereaved Christian friend.

Approval Junkie

Comedian Faith Salie’s new solo show Approval Junkie, based on her book of the same title, is funny, insightful and heartfelt. Salie is an Emmy Award–winning journalist best known for her roles on NPR's Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me! and CBS Sunday Morning. In her one-woman show, Salie begins with the adolescent need to seek approval. Her play explores the concept of the human need to be accepted and even revered.

Charmed Life: From Soul Singing to Opera Star

Many an autobiographical solo show has been born from hardship— growing up closeted, say, or having an intolerable job, or living through a war. Lori Brown Mirabal’s jumping-off point is the complete opposite. It’s right there in her show’s title, Charmed Life: From Soul Singing to Opera Star.

Incantata

Incantata, by Pulitzer Prize–winning Irish poet Paul Muldoon, is an elegy crafted into a theatrical narrative that loosely weaves together erudite poetic imagery and concrete memories with literary and artistic references. The experience is a journey through bumpy waters, a sensory and linguistic adventure with Stanley Townsend, a tremendously talented and physical actor, at the helm of the solo show.

A Sign of the Times

The solo play A Sign of the Times stars Javier Muñoz as a former physics professor who now works as a traffic controller near a construction site. Sounds of vehicles zooming past, slowing down or screeching to a halt are heard frequently, and Muñoz occasionally speaks with their unseen drivers.

Miss America’s Ugly Daughter

The life of Bess Myerson, the only Jewish woman to have won the Miss America title, in 1945, was two sides of a coin: the face was that of a very beautiful, proud, and successful woman, but her private life involved difficult relationships, most notably with her daughter, Barbara (Barra) Grant. Their mother-daughter interaction, and Bess’s attempts to create her daughter in her own image, are the center of Grant’s solo play/memoir Miss America’s Ugly Daughter. The audience never sees the subject, but she is sometimes heard offstage, her voice (by Anna Holbrook) always booming and intruding in her child’s life.

Happy Birthday Doug

Drew Droege made a big splash with his 2017 hit Bright Colors and Bold Patterns, in which his main character, Gerry, attended a gay wedding whose intendeds had asked on their invitation that nobody wear bright colors or bold patterns. Droege’s solo performance as Gerry let one know the other characters through his reactions to them. Now he is back with another solo show keyed to an important event: Happy Birthday Doug. And once again, he is making mincemeat of stereotypes in the gay world.

A Jewish Joke

A Jewish Joke is a one-man show about partnerships, but that is just one of its several paradoxes. The play explores Jewish comedy, though from the serious viewpoint of its effect during the era of the Hollywood blacklist, when humor could either get a guy out of a jam, or reinforce anti-Semitic stereotypes. Many old jokes are told during the 90-minute production; however, they are delivered with such odd undertones that it is impossible to tell whether director David Ellenstein was hoping for legit laughter or uncomfortable sighs from the vintage zingers that are rife with sexism and prejudice. And Joke is a play about writing which, when it falters, does so because the script is, at times, contrived or repetitious. When it succeeds, it does so because Phil Johnson, of San Diego’s Roustabouts Theatre Company, so fully inhabits his role that his character’s stressed-out persona transcends the page.

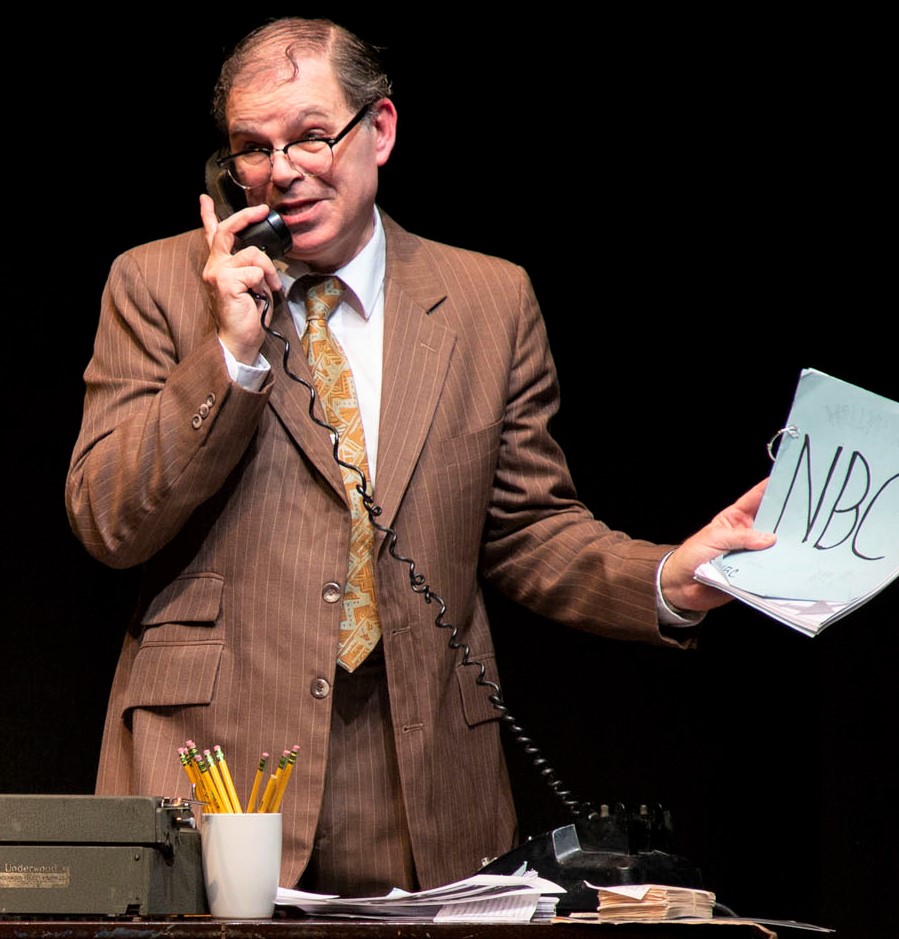

Phil Johnson as Bernie Lutz in A Jewish Joke, written by Johnson and Marni Freedman.

Johnson portrays Bernie Lutz, a film writer for MGM Studios in its mid-20th-century heyday. Though successful at his craft, he looks the worse for wear. His sad brown suit is wrinkled, his tie atrocious, his eyeglasses cheap, and his limp comb-over barely covers his scalp. He would be considered Kafkaesque, except that on this particular morning he finds he has been transformed into, not a cockroach, but a commie. His name, along with that of his lifelong friend and writing partner, Morris Frumsky, have turned up in Red Channels, the right-wing publication that, in 1950, accused scores of entertainers and journalists of having ties to the Communist Party (Real-life names cited by Red Channels ran the artistic gamut from Orson Welles to Dorothy Parker to Leonard Bernstein.).

It seems Morris had recently taken Bernie to a soirée that was more than just the cocktail-weenie extravaganza Bernie thought it to be. The fact that Morris is nowhere to be found as the play begins, despite the fact that their latest flick, The Big Casbah, is set to premiere that very evening, telegraphs all we need to know about Bernie’s impending doom. But Johnson, who co-wrote the piece with Marni Freedman, walks us through Bernie’s very bad day nonetheless. First, it turns out that the government had sent him a warning letter regarding the “important work of investigators under Senator Joseph McCarthy,” but he conveniently had torn it into three pieces without bothering to read it, allowing him to now build tension by slowly finding each section amid the piles of crumpled papers strewn about his bungalow. Then his colleagues begin disassociating. Danny Kaye shows him the door. Louis B. Mayer has no time for him. And when Harpo Marx gives him the silent treatment, he reaches a crisis point: testify against Morris to clear his own name, or protect his pal and risk sacrificing his career.

Bernie treads the fine line between comedy and tragedy. Photographs by Clay Anderson.

Without other characters in the room to play against, Bernie frequently turns to the audience and tells one of the many off-color gags he has collected on index cards. Most are groaners and, whether meant to be awful or not, they do keep the audience from becoming too emotionally caught up in Bernie’s dilemma. It’s the old “alienation effect,” a technique pioneered by another member of the Hollywood blacklist, Bertolt Brecht.

Bernie also has framed pictures of his wife and his parents with which to interact. But mostly, he is on the phone. Indeed, the plot revelations are entirely dependent on the seemingly endless number of calls that Bernie makes and receives. The playwrights employ a couple of devices to minimize the drudgery. Rather than repeatedly having to dial the rotary phone, Bernie has an unseen secretary place his calls. Somehow, she is able to do so with lightning speed, adding a surreal aspect to the evening. And Bernie answers the phone each time with a different one-liner (“Bernie’s Yacht Club”). None are particularly funny, but it beats enduring a hellacious string of hellos.

Production supervisor/designer Aaron Rumley provides a desk for Bernie to work behind, and I will just assume that its drawers are full. Why else install hooks across the front of it and glaringly hang from them the scripts that Bernie risks forfeiting? Regardless, Johnson, who has been touring and perfecting this role since 2016, when the show won Best Drama at the United Solo Fest NYC, makes it work, taking his character’s motto to heart: “When there is no mensch, be the mensch.”

A Jewish Joke, by Marni Freedman and Phil Johnson, runs through March 31 at The Lion Theater (410 W. 42nd St.). Evening performances are at 8 p.m. Wednesdays through Saturdays; matinees are at 3 p.m. Sundays. For tickets, call Telecharge at (212) 239-6200 or visit ajewishjoke.com.

Bleach

Tyler Everett, the protagonist of Dan Ireland-Reeves’s compelling play Bleach, takes a utilitarian view of whoring. A recent recruit to the world’s oldest profession, Tyler (Eamon Yates) has figured out how, on any given night, to reap maximal rewards at the intersection of human sexuality’s demand and supply curves.

I’m Not A Comedian, I’m Lenny Bruce

“Obscene, provocative, criminal, controversial”—those are words used to describe Lenny Bruce, the stand-up comedian and scathing social critic who gained popularity in the 1950s and ’60s. I’m Not A Comedian, I’m Lenny Bruce, written by and starring Ronnie Marmo, captures both the acerbic and the soft sides of Bruce, who was a man seeking a voice in an oppressive time for free speech.

The Tricky Part

Almost 15 years have passed since Martin Moran’s The Tricky Part premiered Off-Broadway. In 2004, stories of authority figures preying on children, though in the news, were not the media commonplace they’ve become. This solo drama about the author’s sexual relationship with an adult counselor from a Roman Catholic boys’ camp was an eye-opening tale of childhood trauma and its myriad aftereffects. Back then Moran’s accomplished performance of his own material, mixing pain and humor, registered as valiant self-exposure, affording audiences unprecedented insights about a stigmatized subject.

Martin Moran displays a photograph of himself at age 12 that was taken by camp counselor Bob. Top: Moran addresses the audience in the Barrow Group revival of The Tricky Part.

Over the past decade and a half, society has become increasingly conscious of predatory sexual behavior. It’s now accepted that this gruesome social phenomenon has always been more prevalent than acknowledged. The topic permeates media discourse, so it’s no wonder that the Barrow Group, the theater company with which Moran developed this play, is reviving it. But is it possible, after all that has been learned, for The Tricky Part to retain the supercharged impact it had in those less wised-up days when it premiered?

Honored with a special citation from the Obie committee and two Drama Desk nominations in the 2003–04 season, The Tricky Part chronicles Moran’s growing up middle-middle class and Catholic in suburban Denver. The academically gifted Marty (as he was called then) was the kind of charismatic kid who regularly lands leading roles in school plays. Seeing the onstage photograph of the 12-year-old, the audience can’t miss how filled with promise this lad must have been in 1972 when counselor Bob—30-ish, likable, and a consummate manipulator—asserted himself as mentor and seducer. (The photograph of Marty, visible onstage throughout the performance, was taken by Bob at the start of their relationship.)

On an overnight camping trip, Bob—rumored to have been a seminarian—fondles the vulnerable Marty. Drawing the boy into his sleeping bag, Bob initiates three years of sexual dominance that are followed by years of residual influence. The barely pubescent Marty knows nothing of sex beyond an elliptical account in the Boy Scout handbook. He’s conscious of being attracted to men (a fact Bob must have sensed), and he’s simultaneously aroused and repelled by Bob’s adult body and his caresses.

The bond that develops between man and boy becomes an obsession for Marty, upsetting his emotional balance with a blend of guilt, shame, and fear. Tormented by suicidal thoughts throughout high school, Marty has close calls with pills and his father’s .22. In due course, his anxious, depressed adolescence is replaced by a depressed adulthood that’s haunted with recollections of Bob’s misconduct and marked by compulsive sexual behavior.

Moran at an exuberant moment in his autobiographical monodrama. Photographs by Edward T. Morris.

Seth Barrish, who directed the original, does the same for this production, showing the delicacy of a conductor interpreting a complex symphony transcribed for a single instrument. In the course of 90 minutes, Moran’s performance varies widely in tempi and dynamics, yet the momentum never lags.

Elizabeth Mak’s lighting, effective throughout, is crucial to the dramatic power of the sequence depicting Bob’s first sexual overture and Marty’s capitulation. This long, central scene would be raw and discomfiting under any circumstances, but Mak, by decreasing illumination gradually until nothing is visible except the actor’s face, lends it an unnerving sense of intimacy.

At 58, Moran still has sufficient boyish charm to be credible as he travels backward in time. His beautifully written script steers clear of self-pity, pop psychology, and agitprop, and dramatizes with exquisite simplicity a complex individual’s response to adversity. Since the original Off-Broadway engagement, Moran has performed this drama for runs of various lengths in London, San Francisco, Seattle, San Jose, Denver, Canada, India, and Poland. Yet his emotional interpretation of the script and all its characters is vivid, believable, and unremittingly forceful, as though he’s living these experiences for the first time.

What’s “trickiest” about Moran’s saga is that his relationship with Bob, both historically and even after the confrontation that provides the play’s climax, has positive as well as sinister aspects. “I want to disown it,” says the grown-up Martin, “but it flashes through me that with this guy I rafted a river, watched a calf being born, cleared a field, conquered a glacier, learned a heifer from a Holstein, a spruce from a cedar.” Bob did damage, yet Moran wouldn’t be the strong figure he is today, nor would his play have its distinctive moral voice, without the totality of his experiences.

The Tricky Part runs through Dec. 16 at The Barrow Group (312 W. 36th St.). Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. Thursday to Monday; matinees are at 3 p.m. Dec. 8 and 16. For information and tickets, call (866) 811-4111 or visit barrowgroup.org.

On Beckett

Aficionados of the bleak works of Irish playwright Samuel Beckett may want to pay a visit to the Irish Rep’s production of On Beckett. But be advised that a passion for the author is a helpful prerequisite. Actor-comedian Bill Irwin takes a deep dive into the works of the Nobel Prize–winning playwright—he calls it a “personal memoir.” Irwin proves a trustworthy guide through several of Beckett’s works, from the world-famous Waiting for Godot to the obscure work Stories and Texts for Nothing.

At the start, Irwin says wryly, “My knowledge of Samuel Beckett’s work is deep. In places.” One of those places is Waiting for Godot, a peak of modern dramatic literature. Irwin played Lucky in the 1988 Broadway production with Steve Martin and Robin Williams, and he shares a story or two about it; the character of Lucky is mostly silent except for a burst of energy in a rambling five-minute speech. In a 2009 Broadway revival he played one of the two tramps, Vladimir, to Nathan Lane’s Estragon. Even though Irwin may be best-known as a silent clown like Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton, his dramatic bona fides are also rock-solid. He won a Tony Award in 2005 as George, opposite Kathleen Turner in Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? All those talents come into play in On Beckett.

Bill Irwin indulges in baggy-pants clowning for his performance of On Beckett; it contrasts with the grimness of other passages (top).

At the Irish Rep, Irwin performs on a nearly bare stage, and most of the show is a solo turn. (For the last moments of Godot he brings on a young actor, Finn O’Sullivan, who plays the boy who appears at the end of both acts to announce that Godot isn’t coming, but he will be there the following day.)

Irwin addresses the minutiae of Beckett scholarship, starting with pronunciation. Is the title character pronounced God-OH or GOD-oh? (The British prefer the latter pronunciation; the former is generally American.) He says that he used to pronounce it the American way until the Broadway production, directed by the British Anthony Page.

“Why does this writing call me?” he asks. “All I can say is we were taught to emulate Socrates—my generation—good liberal arts citizens. Taught to emulate Socrates—except for the suicide—and the gay sex—but we were urged to examine our lives—lest they be found not worth living.”

While Irwin eventually tackles Waiting for Godot, he delves into the much less-known Texts for Nothing, a series of numbered prose monologues, bringing out the poetry and the bleakness in the works:

The graveyard, yes, it’s there I’d return, this evening it’s there, borne by my words, if I could get out of here, that is to say if I could say, There’s a way out there, there’s a way out somewhere, to know exactly where would be a mere matter of time, and patience, and sequency of thought, and felicity of expression. But the body, to get there with, where’s the body? It’s a minor point, a minor point. And I have no doubts, I’d get there somehow, to the way out, sooner or later, if I could say, There’s a way out there, there’s a way out somewhere, the rest would come, the other words, sooner or later, and the power to get there, and the way to get there, and pass out, and see the beauties of the skies, and see the stars again.

And Irwin’s analysis of this long passage is as erudite as you’d find in a college seminar:

Those last lines echo the final lines of Canto 34 of Dante’s Inferno—as the characters climb back up from Hell: “And so we came up and once again beheld the stars.” And that line is the epigraph in William Styron’s book Darkness Visible—A Memoir of Madness. About severe depression. “Darkness visible” is a line of Milton’s, from Paradise Lost. There seem to be some shared touchstones for all who have descended to a hell, and returned.

Irwin discusses the importance of various hats used by Beckett characters. Photographs by Carol Rosegg.

To leaven Beckett’s grim worldview, Irwin brings spoonfuls of sugar with his own expert clowning into play. He dons baggy pants, an oversize coat and various hats—a boater, a bowler (standard issue for the tramps in Godot) and a porkpie, among others. Physically, he slouches, wambles, and stands straight, and at one point does a classic bit of business involving pressing a button at a podium that purportedly makes the podium rise or descend. There is no mechanical apparatus, of course: he is creating the illusion through his own extraordinary physical grace.

On Beckett is a perfect marriage of actor to material. Irwin loves it, and one can’t imagine a better guide, with more insight, into the touchstones of modernism that Beckett created.

Bill Irwin’s On Beckett runs through Nov. 4 at the Irish Repertory Theatre (132 West 22nd St., Manhattan). Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Tuesday and Thursday and at 8 p.m. Wednesday, Friday and Saturday; matinees are at 3 p.m. Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday. For tickets, call (212) 727-2737 or visit irishrep.org.

Sakina’s Restaurant

Director Kimberly Senior engages the audience from the first beat of Sakina’s Restaurant, performed by its author, Aasif Mandvi, for the 20th-anniversary production of his Obie Award–winning play. Dispensing with the fourth wall, she introduces the central character, Azgi, carrying a suitcase in the aisle of the auditorium, and he lights up the space with his greeting, “Hello, my name is Azgi,” a bright, toothy smile and a twinkle in his eye. Azgi has received a letter from America and is about to set off on the journey of a lifetime—leaving his native India to live and work in a restaurant in the U.S.

Beep Boop

Richard Saudek, the creator and performer of the one-man show, Beep Boop, is a self-confessed “idiot who likes to make faces at himself in the mirror.” If his program bio is to be believed, “when he was ten, he ran off to perform in the circus as a young clown, then left the circus at the age of sixteen to pursue other theatrical stuff, such as commedia dell’arte in Florence; improv in Chicago; stilt-walking in Shanghai; burlesque opposite Steve Buscemi; and has portrayed madmen and fools for over a decade all over NYC.” Whether Saudek’s resume is 100 percent accurate or not, one thing is certain: his kind of rigorous talent does not happen overnight.

Intrusion

Discussing rape is not easy in any context. It has scarred our collective humanity; in many societies it is still a taboo subject; it is almost too offensive to broach. Intrusion, a one-woman show written and performed by writer/actor/activist Qurrat Ann Kadwani and directed by Constance Hester, finds a way.

My Life on a Diet

My Life on a Diet, Renée Taylor’s hilarious one-woman show (cowritten and codirected with Joseph Bologna, her late husband), is a testimony to the power of a story and the story teller. In a beautifully beaded champagne evening dress and matching sneakers, she’s the size of a pixie and just as energetic. When she told her doctor she’s going to do a one-woman show, he wonders how, at 86 years old, she’s going to move around the stage for an hour and a half with arthritis, bursitis, sciatica, the beginning of osteoporosis and a broken foot? She tells him “I can jump! I can kick! I can do the mambo!” Then she admits: “In the pool. On dry land, I can walk and I can sit. I just have trouble sitting after I walk and getting up and walking after I sit.” So, she arrives at a happy medium and stays seated for her performance.