A few lucky members in the often anonymous, crowded world of Off-Off-Broadway theater have found themselves lucky enough to be heralded for their work during the past season with a nomination in this year's annual Innovative Theater Awards.

Executive Directors Jason Bowcutt, Shay Gines, and Nick Micozzi created the New York Innovative Theater Foundation, a not-for-profit arts organization, to recognize the great work being done Off-Off-Broadway, to honor its artistic heritage, and to provide a meeting ground for this extensive community. According to the New York IT Awards Web site, "The organization advocates for Off-Off-Broadway and recognizes the unique and essential role it plays in contributing to American and global culture. We believe that publicly recognizing excellence in Off-Off-Broadway will expand audience awareness and appreciation of the full New York theater experience."

The voting process for the IT Awards, to be held Sept. 24, gives audiences input (their online votes count for 25 percent) while encouraging companies to see each other's shows. When a production submits itself for competition, three cast, crew, or production team members are required to go out and judge other productions. In this way, the creators hope to facilitate a greater sense of community and relationships among the many diverse (and busy) Off-Off-Broadway artists.

The nomination ceremony itself took place at Our Lady of Pompeii in the West Village on July 16. This year's nominees included artists from several boroughs as well as multiple nominees. There are 11 people with dual nominations. Ryan Maeker, for example, is a double nominee in the sound design category for both La MaMa's Dancing Vs. the Rat Experiment (as a co-nominee with Tim Schellenbaum) and the silent concerto at Packawallop Productions. Israel Horovitz is a double nominee in the Outstanding Original Short Script category for his works Beirut Rocks and The Hotel Play, both of which were at the Barefoot Theater Company.

"Practically speaking, it'll probably mean neither play will win because the double nomination will split the votes of my fan base," predicted Horovitz. But his outlook was mostly optimistic. "It means that somebody actually saw my plays and was moved by them, and that means a lot to me. And, of course, even I, at my cynical worst, know it's a hell of a lot more fun to be nominated than to be overlooked."

Rob Urbinati, nominated for Outstanding Original Full Length Script for Prospect Theater Company's West Moon Street, also wrote the musical Shangri La. Both shows were nominated in their respective outstanding production categories. "I was very pleased that both shows were nominated by a group of my peers," he said.

"What a surprise!" exclaimed Marnye Young, a nominee as Outstanding Actress in a Leading Role for East Coast Artists's Waxing West. She said the nomination was an additional reward on top of the show itself. "I was stunned with the response. I knew it was a gorgeous script in the hands of an extremely talented director and an incredible cast and crew. But this is New York, and you never know what you have until you put it in front of an audience."

Overall nominee reaction was one of gratitude and generous praise. Judith Hawking, nominated for Outstanding Actress in a Leading Role for West Moon Street, said, "Everyone from the producers to the stage managers, the designers to the box-office people, treated this play and its players with the utmost respect and support."

Justin Cooper, nominated for Outstanding Original Short Script for Wood, his contribution to Workingman's Clothes Productions's f---plays, was also quick to spread praise. "Amy Lynn Stewart and Steven Strobel are hugely talented, amazing actors who brought such life and humanity into the characters I wrote for them that I couldn't watch a single performance without being blown away and utterly impressed by their command of their craft."

Cooper went on to compliment his director, Steven Gillenwater, who "imbued [Wood] with a wealth of small touches that showed his genius and his ability to find pieces of the story and characters that go way beyond just what's on the page."

Suzann Perry, nominated for Outstanding Actress in a Featured Role for Strom Thurmond is Not a Racist/Cleansed at the Immediate Theater Company, echoed the other actors' feelings of camaraderie with the director and cast. "Jose Zayas is a very talented director and a pure delight to work with. The cast was amazing, a truly gifted group of actors. So giving and connected."

Jon Frazier, an Outstanding Actor in a Featured Role nominee for Urinetown The Musical at the Gallery Players, said, "I was fortunate to be able to play with some very talented people." Frazier went on to note how encouraging his IT nomination was. "I am still very new to the New York theater and on-camera scene. I was picked up by an agent during this production of Urinetown, and so now I am just chugging along as best I can. I have had to somewhat start over when I moved here. I am pounding the pavement, so to speak, till I get the next job."

Joe Curnutte, who played multiple characters in the one-man male rape drama Thinking Makes It So at Examined Man Theater, expressed similar vindication with his Outstanding Solo Performance nomination. "I have only been in NYC for a little under two years, so I am just now becoming privy to all the underground goodness that is the Off-Off world," he said. "It sort of means that I am doing what I am supposed to be doing. Not that you have to be noticed in order to know that, but I really feel like I fit in here."

Ever the trouper, Curnutte will be unable to attend the September ceremony, as he will be performing at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Other nominees are keeping busy too. Young will star in a production playing at this month's New York International Fringe Festival called End's Eve, while Horovitz is working on a multitude of projects, including a film adaptation of his Park Your Car in Harvard Yard, starring Julianne Moore.

Cooper praised the IT Awards for their generosity. "There are so many thousands of plays opening Off-Off-Broadway in this city every year, with so much talent and drive behind each, that it is incalculable to think that my script for Wood is one of the six to have this beautiful light shine upon it."

Warren Kelley, an Outstanding Actor in a Leading Role nominee for Strings, at the Open Book, said, "It's really wonderful to be nominated for an IT Award. I think it's terrific that this award was created specifically to honor the extraordinary work that is happening Off-Off-Broadway. Off-Off was first created specifically to give professional theater artists an opportunity to showcase their work. It has become so much more than that now. It is a place where work can be developed and nurtured."

Refer to the NYIT Awards website for a full list of the nominees.

Undead

In 1922, when German film director F.W. Murnau released Nosferatu, A Terror-Symphony, a silent adaptation of Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula, he could not have imagined the afterlife that his film and its creepy lead actor, Max Schreck, would wrest from oblivion. In movies, Werner Herzog remade Nosferatu. Tim Burton named the debonair corporate villain of Batman Returns after Schreck, and in Brooklyn auteur E. Elias Merhige's The Shadow of the Vampire, John Malkovich played Murnau coaching Schreck—a real vampire—to just play himself.

At this year's Midtown International Theater Festival, Rabbit Hole Ensemble is reviving the legend again, in Stanton Wood's new play, Nosferatu: The Morning of My Death, the second work in the company's trilogy of Dracula-inspired plays. Morning is both a worthy successor to Murnau's film and an original response to it. It is not a direct adaptation of Murnau's film, nor of Stoker's novel. Instead, it is the first-person account of their heroine, named, as in Stoker's novel, Mina Harker.

For Morning's Mina, the cruel yet charming Count Nosferatu has one redeeming quality. He offers her the chance to cross borders and break boundaries—literally, the boundaries between life and death, but also the various social boundaries that imprison Victorian women. After Mina's vampire-induced sleepwalking lands her in an insane asylum and a straitjacket, the asylum director's wife regrets that "it felt wrong to put her there." "Had to be done," the doctor says, shrugging.

In telling the tale from Mina's viewpoint and making it a struggle between Victorian woman and her ordinary life-drainers, Wood recalls Francis Ford Coppola's inaccurately titled 1992 film Bram Stoker's Dracula. However, Wood's deft, theater-style handling of the story and his empathetic excavation of Mina's inner monologue make Morning lively and haunting, if not quite new.

The acting in the lead roles is as strong as Wood's writing. Jenna Kalinowski's Mina is passionate without being melodramatic, sensitive yet never sentimental, and increasingly indignant. As the madhouse inmate Renfield, Danny Ashkenasi is frighteningly accurate. His wide-eyed ranting is zany yet natural, and watching him mime eating flies is nauseating. Paul Daily plays Mina's husband as a bland, irritating Dudley Do-Right, but that's exactly how Jonathan is supposed to be.

Matthew Cody, as the vampire, speaks in a gruff, gritty voice. The ensemble repeats his lines after him, creating an echo effect that couldn't be done better with technology. Cody's portrayal of the character is nuanced and three-dimensional, radiating both arrogance and alienation.

Cody's makeup (by Courtney Daily) and costume emulate iconic elements from Schreck's look—the white face, the black suit, and the extra-long fingers that taper into sharpened knife points. Thankfully, Daily eschews the outsize putty nose that Murnau may, disappointingly, have lifted from the visual lexicon of Weimar anti-Semitism.

Director Edward Elefterion's blocking often makes Nosferatu appear to Mina from upstage, his pale face and hands seeming to float in the darkness surrounding her. This reinforces Wood's suggestion that he is not only Mina's confidante but also her alter ego, the rebellious double that her husband and his society try to kill.

Elefterion's lighting design is as evocative as his directing. The lights, including some manually manipulated by the actors, cast their shadows on black curtains upstage, referencing but never copying Murnau's famous exploitation of shadow theater. Elefterion is clearly a director to keep watching.

This coming Halloween, Rabbit Hole Ensemble will present its entire Nosferatu trilogy. Until then, the Midtown International Theater Festival offers a great opportunity to preview the work. Like its antihero, you might decide that one taste isn't enough.

Who's Cheating on Who

Gary is having one heck of a bad week. In addition to being subordinated by his secretary, Bethany (Monica Yudovich), a woman unfamiliar with the term "too much information," the poor guy has just received some startling news. His wife, it turns out, has been having an affair with his best friend, Paul (Shane Jacobsen). She's been unfaithful with someone else too—Paul's own wife, Gail (Katie Kreisler). Both Paul and Gail go on to describe their rabid sexual encounters with Gary's wife in Alex Goldberg's cutish play I'm in Love With Your Wife, but this is no live-action Kama Sutra. It's a wake-up call for Gary (played to good comic and frustrated effect by Ean Sheehy) to reclaim his own life.

With each scene in Wife, Goldberg raises not only the silliness factor but also the character count. After surviving the confessions of his two friends (and apparently an additional affair between the equally freewheeling Bethany and Paul), Gary recounts these latest developments to his psychiatrist, Dr. Feldberg (Ron Palillo of Welcome Back, Kotter). Like most therapists in comedic pieces, Feldberg has just as many quirks as his patients do. He continually breaches patient-confidentiality trust and hints at an unhealthy obsession with actor Jon Voight.

Still, he's Gary's only hope for a personal breakthrough. The two use a "color therapy"—in which Gary personifies his emotions of the day as a color, with the hope of getting to their cause—that actually makes a good deal of sense. In these therapy scenes, Sheehy does a sly job of fusing comedic haplessness with dramatic intensity.

Rather than urge Gary to confront his wife, or Paul and Gail, Feldberg tells him to go ahead with his plans to throw a dinner party in his apartment with his wife and their adulterous friends. Before one can say "inkblot," Feldberg has invited himself to the shindig.

Moreover, he has corralled himself a date in the form of Ruth (Marion Wood), an aspiring actress who happens to be the patient Feldberg sees after Gary. As if these complications weren't enough of a clue that Goldberg does not know how to quit when he is ahead, he piles on another twist. As an acting challenge, Ruth will pretend to be a Ukrainian expatriate. This type of plotting is gratuitous; it doesn't add humor, just running time. That said, Wood is a standout in the role, with deft timing and a great sense of physical comedy.

Roughly the second half of Wife consists of the dinner party, to which Bethany has also invited herself. Throughout this extended scene, various cast members excuse themselves to go offstage to cavort with Gary's wife. As one might have guessed by now, this vixen is never seen—it would diminish her reputation to humanize her. So Wife starts to sink into a puddle of silliness.

Director Tom Wojtunik has a good track record. His 2005 Fringe Festival entry, The Miss Education of Jenna Bush, was a smart send-up of wanton shallowness that still had a beating heart to it, and his stewardship of the Gallery Players's Urinetown just landed a New York Innovative Theater Award nomination for Best Musical. He constantly finds ways to block his six actors so as to break up the action, but Goldberg doesn't know when to call it quits, and Wojtunik seems at a loss to rein this show in. Paul and Gail become increasingly cartoonish, and Gary's desperation reaches a fever pitch long before he finally does anything about it. As a result, this play just moves in circles for almost a half-hour.

Yet Wife is certainly worth seeing. As Gail, Kreisler has a lot of presence, and her early scenes, including a raunchy moment with the effervescent Yudovich, are quite amusing. I would like to see her command the stage in a larger role. Jacobsen is charming too, though the Lothario he plays lacks the sharp edges that come with playing such a character.

Palillo, for his part, artfully underscores his character's zaniness with a hint of insecurity that also explains why he can get to the heart of Gary's own problems. All six actors provide nice touches, but the play spreads their big moments too thin. While it shows potential, I am not sure there is a full-length play here.

Through the Years

Everybody has turnoffs when it comes to theater. For some, nonintegrated song-and-dance sequences (as when a song is shoehorned into a musical rather than fitting in organically) are a mood killer. Others are left cold by a heavy-handed use of deus ex machina. My theatrical turnoff is when a show begins with actors acting "natural" onstage, preparing for a show—especially when they're wearing "crazy" apparel like suspenders and bowler hats. Fearing that I'd walked into a production of Godspell by mistake, I was greeted by such an entrance at the Rising Sun Performance Company's new work, DeCADEnce. Though I tried to shake off the contrived prologue, the rest of the show, unfortunately, lived up to my grim expectations and then some, as a high-concept, poorly scripted, under-rehearsed, and overly long bit of self-indulgence.

The show's aim is to shed light upon the excesses and dirty secrets of the 20th century through a vignette from each decade, introduced by a title card projected on the wall. From the murder of an elephant at Coney Island in 1903 to President Clinton's infidelity in 1998, the show mostly goes for a presentational and artificial style, with misguided forays into realism that the costumes and performers cannot sustain.

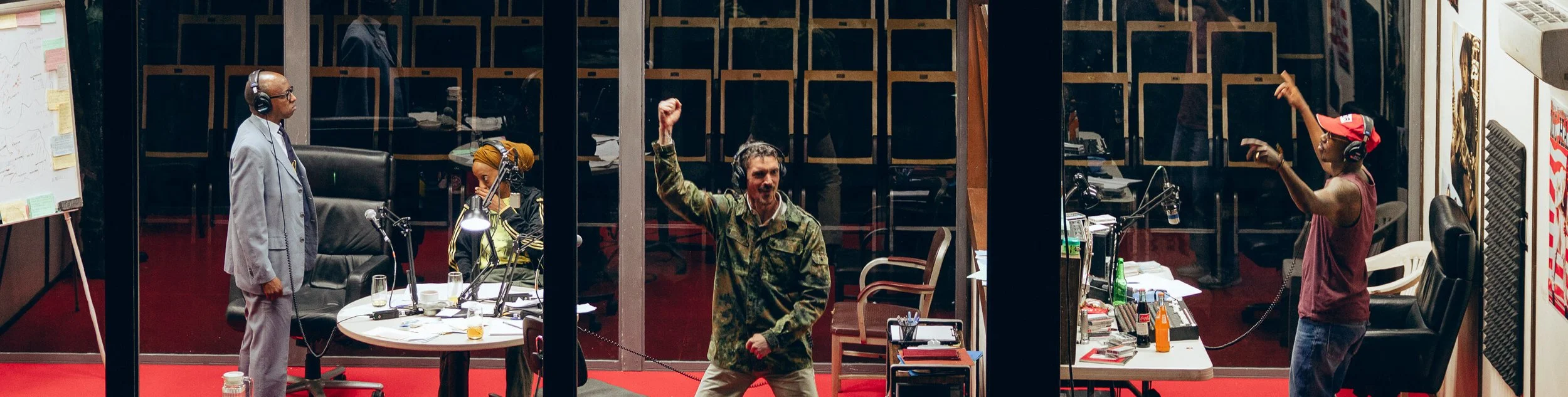

The two segments that are most effective are the melodrama "Arpeggio" in RadioPlay (1934) and the filmed sitcom "The Jaunts of Jare-Bear" in TVPlay (1955). Both take a satirical look at the popular leisure activities of the time and their insistence on putting forth an unrealistic view of the country's economic situation and the typical nuclear family, respectively. These pieces seem to have benefited from extra rehearsal and direction, and it shows in the performances as well as the overall finished product.

In MinstrelPlay (1913), the segment started off promisingly with a look at a middle-class black couple. The husband, a Shakespearean actor, is not being taken seriously by critics or the public, and his wife beseeches him to move into the song-and-dance medium, which is the only genre that accepts black actors. He is appalled by the suggestion that he swallow his pride and play one of these denigrating roles.

Then two white actors present a piece in blackface, meant as a counterpoint and an illustration of the mean-spiritedness of this so-called "entertainment." What should be an offensive and uncomfortable look at our own sordid past is instead a feeble stab by actors who are either too embarrassed or ignorant of the performance style to emulate it properly. The characters are not broad enough, the accents are wrong, and the musical number seemed slapdash and rushed. If you're going to do blackface, go all the way. And if you're not comfortable with it, show a real example from a film, such as Holiday Inn, Dimples, or Babes in Arms.

As a whole, the production seemed more caught up in its message than in presenting it in a coherent way. The segments were not polished enough, so that the point of view was either lost in the shuffle or pushed awkwardly to the front.

There were also performance problems, with actors rushing their lines, other actors going up on their lines (two weeks into the run, no less), choreography that wasn't yet automatic, and, worst of all, no sense of knowledge about the time periods from the cast. During the 60s segment (LovePlay), there seemed to be no understanding by the actors of the spirit of the times. Putting on a tie-dyed shirt and spouting Jefferson Airplane lyrics does not a hippie make.

It's admirable when a theater company decides to work on new pieces developed with its ensemble, as the Rising Sun Performance Company was formed to do. However, there needs to be someone, whether writer or director, with a clear vision that is seen through the collaborative process. Too many cooks are apt to spoil the broth, and sometimes they run onstage in their "street clothes" and spoil the show for some of us.

Thanks to You

Watching Amy Staats in her solo show, Cat-her-in-e, is like watching an entire collection of home movies squeezed into one body. Playing all of her relatives, she shrinks into shy, scared children, pulls her neck back to become an awkward, tall teen, and opens her eyes and arms to become a booming stepmom. More important than the skilled shape-shifting, however, is the overwhelming layer of nostalgia that hovers over Staats's performance. As it follows Amy's (her character's name) early reverence and later gratitude for her older cousin, Catherine, Staats's play is literally a thank you card: it begins and ends as she perches in front of a computer, writing to thank Catherine for her wedding gift.

Narrating one's youth is a familiar dramatic formula with a successful history, ranging from A Christmas Story to The Wonder Years. With that in mind, Staats isn't embarking on a particularly innovative or challenging mission. Hindsight almost guarantees hilarity and insight. Perhaps this is why the show is far more successful in its childhood portions. When everyone grows up, the play loses its pace and its place a bit.

We meet Catherine, a reclusive and aggressive type with a penchant for imaginative games and stories, when a 4-year-old Amy visits her relatives for Christmas. Catherine is 12 and not exactly an inspiring personality: she cheats at the Barbie Olympics and chases after her young cousins' dolls with a toy's severed head.

Nonetheless, the young Amy and her 5-year-old sister, Susannah, are obsessed with their older cousin and the schemes she weaves. They beg her to play and bait her to add more unusual details to her tales. The show is fueled by what is either Staats's fabulous memory or meticulous attention to fabricating details. The rules and intricacies of every game are explained to comical and touching effect, while her reminiscing zeroes in on the slightest sights and sounds of her youth.

Staats has a knack for nailing personal quirks and expressions, and it comes through in her multiple roles. To distinguish between family members, she assigns each one a particular (and usually unflatteringly funny) body language. It would be mere ventriloquism, however, if Staats just stuck to these usual postures. Instead, she takes the impressions a step further and ages each character as time goes on. Slightly, a sister's boyish slouching straightens, her own squeaky voice clears up, and her aunt's tight-faced squint seems to gradually pull her skin further and further inward.

With its canary-yellow color, boxy outline, and cinched empire waist, Staats's dress is both childish and womanly at the same time, allowing her to jump from Aunt Anne to a baby version of herself in a beat. Usually, the older women place their hands on their hips in some way, accentuating a shapelier figure, while the kids awkwardly slump in their bodies.

Of course, as the characters grow up, talk of marriages and careers replaces playtime. While Amy has started acting in New York and has seen some success, a thirty-something Catherine is living alone with her cats and still trying to put a medical school application together.

When an adult Amy invites herself over to her aunt's house after not visiting for five years, she feels awkward and unwelcome. "I realize I am trespassing," she says. The statement raises an interesting question: is the play itself a violation of privacy? While thanking her older cousin, Staats makes the contrast between Amy's exciting city life and Catherine's plateau so obvious that the resulting portrait of her cousin is far from flattering.

Ironically, the play seems most condescending when Amy tries to express her gratitude. The script sometimes treats her success as Catherine's biggest accomplishment. She explains that "61% of the things I've done in my life have been influenced by you."

This self-indulgence is the play's biggest flaw. It's reminiscent of the adage: "Enough about me. What do you think about me?" The audience is supposed to care about Catherine, but she fades in and out of the picture too much for us to truly understand her. Instead, we are left with a coming-of-age story that is mostly about Amy. It's an entertaining and often smart piece of theater, but perhaps Cat-her-in-e is the wrong title.

Triple Noir

In the cult 1950s noir film The Shadow-Pier, socialist-leaning World War II veteran Johnny, his African-American best buddy Justin, and sweetheart Corinne battle the forces of evil, as personified by Ocean City, Md., property developer Mr. Barnardine. All their fates will be decided on the salted boards of Ocean City's creepy Shadow Pier, which is also the name of Barnardine's sleazy resort. This film became a cult obsession because it was shown only once—and only partially—before one Agent Spencer, of J. Edgar Hoover's FBI, arrived to shut it down for promoting Communism—or "racial harmony." Like another 1950s classic, Rebel Without a Cause, The Shadow-Pier achieved notoriety as a "cursed" film, because all of its actors died early, unnatural deaths.

The major difference between Rebel and The Shadow-Pier is that the latter was never made, except in Jonathan Wallace's brilliant new play, also titled The Shadow-Pier. A winner of Abingdon Theater Company's prestigious Christopher Brian Wolk Award, the play is being premiered by the Howling Moon Cab Company as part of the Midtown International Theater Festival.

Wallace's play consists of three interwoven narratives—that of the fictional film; its creators' battles with McCarthyism, as personified by Agent Spencer; and a modern standoff involving the film's ghostwriter (the last living member of the creative team), a modern film scholar desperate for tenure, and an insane former FBI agent who builds bombs in his basement and claims to have a unique, extant copy of the film.

What will Johnny do to get Corinne back from the vicious Barnardine? What will actor Ed Hudgins (who played Justin), film financier Eliane Tenbroek, and cinema owner Sam Stein do to keep themselves off the blacklist? What will film scholar Moira Spelling risk for job security? And can haunted ghostwriter Ferry Tenbroek prevent the curse of The Shadow-Pier from claiming any more lives?

Wallace's script explores each of these questions with an equally riveting dose of suspense. He adroitly exploits the fragmentation of the three narratives to increase the tension. James Duff's stylized, minimalist direction highlights the noir atmosphere with tableaux that look as if they came from 50-year-old reels.

The Shadow-Pier is complicated, but it isn't a mess, structurally speaking. Wallace has supplied a clear protagonist in Ferry (Peter Reznikoff), who, when contacted by the film scholar and the psychopath (Jared Morgenstern), fights his instinct to leave the cursed film safely submerged in his memory. Forced to recall the dark days of the 1950s and the lessons in the film itself, he constantly calculates his risks, just as any film noir hero does.

Reznikoff's Ferry is a haunted but ordinary old man. His pain and grief are detectible but never exploited for melodrama. All four actors play one role in each of the three narratives, and they switch between their roles with creative versatility and great clarity. In particular, Reznikoff's handling of the switches between the reserved patrician Ferry, the energetic first-generation-American Stein, and a cardboard-nasty Barnardine is impressive.

As the scholar Moira, Ferry's alcoholic, film-financing cousin Eliane Tenbroek, and film heroine Corinne, Gayle Robbins shows an intensity reminiscent of Katharine Hepburn. At the same time, the contrast between her self-assured, put-together Moira and her scatty, sloppy Eliane is huge.

The costumes, like the actors, do triple duty. Melanie Swersey's black, white, and gray outfits lend the film-within-a-play scenes a good deal of noir verité. Minor changes, such as the addition of plastic glasses or removal of the men's hats, change the era and the character instantaneously. The set, by Elisha Schaefer, remains the same: the wooden pier dominates the film scenes and, like its namesake movie, haunts the worlds of its creators in the 1950s and their 21st-century survivors.

It is not often that one sees a play that takes genuine aesthetic and structural risks while having something real and vital to say. The Shadow-Pier, like the film within it, is a masterpiece waiting to be dredged up and shown to the world. Brave the curse and go see it.

House of Cards

Two brothers engaged in sibling friction is familiar territory for American drama. From Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey Into Night to Arthur Miller's The Price and Sam Shepard's True West to the recent Neil LaBute play In a Dark Dark House, fraternal jealousies have provided potent theatrical fodder. In Padraic Lillis's Two Thirds Home, Paul, a poet and teacher, and his brother, Michael, a businessman, enter their childhood home to gather important papers. The house is now inhabited by Sue, the woman whom their mother, Anne, shared her life with for more than a decade. It's the day of Anne's funeral, which has gone bumpily for both men.

Ryan Woodle's Michael, the older brother, is efficient and bossy, and it's no surprise that various resentments fester within him. Aaron Roman Weiner's long absent Paul is swept away by nostalgia about the house and a rosy childhood. But there is some tension between them about their career paths and monetary success; Michael snipes at Paul for pursuing a creative but not lucrative profession. And because Anne never publicly acknowledged her relationship with Sue (played with sympathy and composure and the patience of age by Peggy J Scott), Michael grew up believing it was shameful, and he treats Sue with brusque indifference. They have clearly been at odds and only sidelined their strife during Anne's dying days.

Lillis examines the relationships among these three characters from every possible angle, in a claustrophobic way that draws, perhaps unconsciously, on French neoclassicism. Certainly Two Thirds Home observes Aristotle's unities. There is a single set, on which designer Laura Jellinek prominently showcases Anne's love of books and of family (in photographs). (Jellinek's shrewd design suggests a large, comfortable home in an unbelievably small space, with doors leading to other rooms, and a stairway to a second level.)

As in neoclassical tragedy, the time is continuous. Literary references, from Rilke and John Donne to James Joyce's Ulysses, would have pleased the French academy of the 17th century. If Jean Racine were writing nowadays, he'd recognize a lot of what Lillis is doing, though the lesbianism would have sent him through the roof. Each facet of each relationship is revealed gradually through dialogue.

But Racine is an acquired taste, and unless one acquires it, such drama can feel talky and sluggish. Lillis doesn't entirely escape that pitfall, although the cast assembled and directed superbly by Giovanna Sardelli is outstanding enough to maintain interest in the characters even when the talk sounds repetitive and the plotting seems farfetched. For example, Anne has left the house to be divided equally among her sons and Sue. But if Anne and Sue were together for more than a decade, why didn't Anne make a clear provision for Sue to remain in the house until her death before having the property revert to her sons?

Lillis needs this improbable situation for dramatic conflict—Michael wants to buy out Sue and sell the house, while Paul indulges in a pipe dream of returning and living there. Sue, like many gay spouses, seems marginalized and at their mercy; unfortunately, their clandestine intrusion into the house also betrays a monumental lack of basic manners. The situation ends up diminishing Paul, Michael, and even Anne.

Still, the play tackles important questions about the guilt that arises from avoiding discussion of subjects deemed taboo and the way it can poison relationships. Lillis has a gift for dialogue and an ability to put interesting characters in fresh situations, and his examination of personal privacy versus one's willingness to be open about sexual orientation touches on an issue that resonates deeply among gays and their straight relatives. He's a writer to follow.

The Verdict Is In

After you've seen a few of them, most New York-centric plays begin to seem slightly familiar. They all involve couples, usually financially well-off ones. Their members intermingle in various combinations to talk about their lives, only to break off in different combinations to discuss how the side of their lives the audience has seen is a front for something less satisfied. Nancy Manocherian, the author of Guilty, the current Cell Theater Company production now playing at the Acorn Theater, is—you guessed it—responsible for creating yet another one of those cookie-cutter Manhattanite works. Though it's staged handsomely by talented set designer Tim McMath, one should not judge Guilty solely on its looks. The play that begins once the curtain rises is based on plenty of sex, lies, and photographs, and by the zig-zaggy production's overdue end, the only lingering question is "Why are all of these people friends?"

Manocherian introduces all of her characters at once, at the funeral of the dog belonging to privileged teenager Lindsey (Tracee Chimo). She is the daughter of Marcie (Mary Ann Cook, in too slight a role for her obvious skills as both a comedian and dramatic actress) and Rich, who has just been caught committing some unspecified white-collar crime.

The couple is acquainted with Adam (two-time Emmy-winner Darnell Williams), an attorney, and Jake (Ned Massey), an erstwhile musician who enjoyed some success as a solo act and is trying to make his money last as long as he can. Jake resents Adam's wife Dori (Glory Gallo), a trust fund baby who happens to be close with his wife, Laura (Heather Kenzie), a former groupie with secrets of her own.

Jake also nurses an unhealthy relationship with the bipolar Lindsey. Dori, meanwhile, seeks to reignite a missing spark in her life, not with Adam but by reviving her photography career with her first love, an old college boyfriend with a trendy art gallery.

Manocherian weaves a tangled web, but ultimately to little avail. Guilty never really builds to a climax, or even to any stunning confrontations. And with the major plot points pivoting on her female characters, she gives Massey and Williams very skeletal characters to work with. Both actors are charismatic, but Adam is a character without edge. Meanwhile, Jake should have been a point of entry for a lot of dramatic development. He's a former artist trying to shun all adult responsibilities that have come his way, including fatherhood and fidelity. (Massey also writes and performs Jake's big song.)

Manocherian raises more questions about Jake's past than are answered, yet her interest in the character's predicament seems to wane as she moves on to new territory and choppy subplots. In fact, the most interesting male character is Marcie's larcenous husband Rich, whom the audience never even sees. And throwaway references to him are confusing—is he on trial, in rehab, or in prison? Also, the fact that Adam and Dori's three children are never seen and rarely mentioned undermines the history of their life together.

It is hard to tell if director Kira Simring is in love with Manocherian's plot or at a loss in terms of guiding the work into something more involving. In any case, the result feels stale. It is nearly impossible to understand what motivates any of the characters to do the things they do, which means when the audience does hear about those things after the fact (the play is more talk than action), it is very difficult to care. And to perform the piece in an uninterrupted hour and 50 minutes is a mistake as well.

As Lindsey and Laura, Chimo and Kenzie do nice, nimble work, justifying their characters' choices from scene to scene. But because these ladies are in a different state of mind every time we see them, a real person never emerges. Ultimately, it is Dori who emerges as the play's core character, and Gallo is remarkable—earthy, sultry, paranoid, nosy—a truly flawed, scared woman. She carries the show, only to have the play force her to deliver an extended monologue near the prolonged end, in which Dori laments her body's betrayal of her in middle age. This type of scene could be lifted right out of the rest of the play; it is stylistically inconsistent, comes too late, and mars a performance that up to then had been perfectly expressive about Dori's worries over aging and her fraying marriage.

All six characters in Guilty make bad choices, some of which are worse than others. Sometimes they hurt each other; almost always they do some damage to themselves. And yet, after all the suffering is said and done, no one really learns anything, the audience included.

Devil's Due

If an episode of The Twilight Zone were spiced with a heaping helping of sexual innuendo and dashed with an exhaustively moral message, the result would look a lot like Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? Written in the 50s by George Axelrod, the story feels every bit like the campy satire of its time. Although Axelrod pokes fun at the Hollywood formula, his story also blatantly subscribes to it. While the characters joke about the shortcomings of filmmaking, they themselves are Tinseltown caricatures: the dumb blonde actress, the easily outraged producer, the perverse veteran, the jaded artist, and the wowed yokel. Complementing the two-dimensional personalities are the thin plot and over-the-top acting. Still, like the beautiful star at the heart of the action, the show is delightful to watch in spite of its vapid quality.

If there were a list of all the stereotypical requisites for being a loser, reporter George MaCauley (Morgan Sills) might check off each item: living with family through adulthood, inexperience with women, a squeaky voice, and, to top it all off, a tacky bowtie. When he's sent to interview sex symbol Rita Marlowe (Jennifer Danielle), the contrast between elite and geek accentuates his shortcomings. What's a man to do to improve himself? Make a deal with the devil, of course!

Lucky (or unlucky, as it turns out) for George, Rita's agent, Irving LaSalle (Tuck Milligan), just happens to hail from Hell. Not the devil himself, he explains that he "merely works in the literary department" down there. Irving offers George a tempting deal: exchanging wishes for pieces of his soul.

Milligan takes a little while to settle into his role, but when he does, he revels in the deliciously evil dialogue. Finishing every line by rising in pitch and suggestively trailing off, his Irving is equal parts master manipulator and English gentleman. The sneering-yet-suave tempter act has been done many times before, but Milligan seems to be having such fun camping it up that you can't resist enjoying every time he pops onstage to torment George.

Compared with Irving's smooth certainty, George is a bumbling bundle of nerves with an expression that suggests he's forever on the cusp of exclaiming "gee-golly!" Even though George receives his initial wishes for love, success, and charm, he still lapses into his old self. While his schoolboy shtick gets a little irritating, Sills shifts from doofus to debonair in a way that's natural and funny. His portrayal manages to be both a tribute to and a parody of the lovable loser of classic films.

The plot itself is rooted in movie-making. Rita is planning to star in a film adaptation of a successful play by a rising-star writer, Michael Freeman (Eric Rubbe). Michael, a love interest of Rita's, also intends to pen the screenplay. But with no writing talent (his only article was a profile of one Rock Hunter), George uses two of his wishes to usurp poor Michael both romantically and professionally.

Oddly, George's wishes grow more selfless as his soul-shedding continues. He even forges a friendship with Michael that ends with unexplainable sacrifices by each of them at the play's conclusion. After more than an hour of amusingly evil buildup, the solution to everyone's problems comes quickly and gets such a breezed-over explanation that it's reminiscent of a Scooby-Doo denouement.

Such a simple remedy would be easier to swallow if it were presented more as an ironic mockery of the cheesy Hollywood ending than a simple mimicry of it. The bland wrap-up seems out of place because the rest of the play laughs at itself more obviously.

Thanks to director Holly-Anne Ruggiero's dance-like blocking and snappy pace, the first two acts are good, fluffy fun. The production's brisk speed does the script's dirty jokes and one-liners justice, as the ensemble delivers each zinger with bite. One standout quip: when George complains to Irving that he doesn't have the talent to achieve his dreams, his agent sneers, "I'm not talking about talent, I'm talking about success."

In this production, the color of success is gold. In contrast to the dominance of white in Act One, set designer Anne Allen Goelz tellingly blankets the stage in gold for the scenes following George and Irving's arrangement (a Fall-like loss of innocence). As everything from garbage bins to clipboards to Rita herself takes on a gaudy metallic shimmer, this overwhelming abundance of "success" starts to seem as tacky as George's bowtie.

Of course, George learns that there's more to life than a gold-plated pencil collection and tries to right the wrongs he's committed on his path to the top. Unfortunately, the play's simply not as fun when it preaches. While the characters might realize you don't need a demon to write a good story, he sure helps this one.

Pool Party

For many New Yorkers, the summertime experience is not complete without a trip outside the city. Getting away from the crowds and the noise and seeing water can be a powerful restorative, even for those who thrive on the aforementioned hustle and bustle. But if your bank account (or boss) says "no" to your vacation plans, consider joining Impetuous Theater Group for a pleasant evening poolside at Swim Shorts 3: Are You In? High atop the Holiday Inn Midtown, with skyscrapers and setting sun as a backdrop, five short plays are presented by a youthful, attractive cast. The shows in July are different from the ones in August, as are the writers, directors, and actors. In the July series, the writers tackled suicide, double-crossing friends, starvation, infidelity, and the Cold War, but all in a lighthearted, semi-serious way.

"Joe the Lifeguard" starred the titular whistle-bedecked hotel employee as he first ignored, then tried to save, a distraught woman from trying to drown herself under his watch. It's a troublesome premise for a sketch, as self-annihilation is a conceit that, when used, must be acted upon, much like the rule about guns onstage having to be fired by the end of a play. The audience members don't want a character's actions to be thwarted, and yet they don't want someone to kill herself either. However, as this is a 10-minute comedic short and not 'Night, Mother, things resolve themselves, comedically though awkwardly, toward the end.

The pool is a stand-in for quicksand in "Forgiveness," as one man (Herb) jumps willingly into the muck and then pulls another man (Steve) in with him in order to talk. Herb and Steve's literal quagmire is also a literary one, as the script doesn't give these two-dimensional characters enough motivation for their ridiculous actions, or legitimate conversation, or even a reason for being anywhere near quicksand in the first place. If Mallory, the guardian angel, didn't appear in full costume later on, the piece could pass for a meandering bit of improv. (Someone should add "pit of quicksand" to "the moon" and "Hell" as another classic example of a bad location to set an improv scene.)

"Jettison" pits man against the elements as three men (Steve, Bob, and Gary) struggle to stay alive in a lifeboat after their ship sinks. The casually coarse dialogue and the personalities of the guys give a semblance of realism to the situation, even as their lifeboat is tethered to the pool's ladders. It's a sad and amusing piece.

In "A Proverbial Affair," the audience is back at a hotel pool as vacationers Kent and Diane meet the sensual body-piercer Nino. While Kent is offended by the free-spirited Cuban, his fiancée Diane begins to shed her Virginia-bred conservative veneer and gets back in touch with her buried Caribbean roots. There is a campy sense of fun in the piece, and it was enjoyable for the audience to be acknowledged as other poolside guests during the scene.

The best of the shorts ("Der Eisbar") had the most fantastical use of the pool: it doubled as the cold waters of the Arctic during the 1980s. American sub meets Russian sub meets German sub—all of them a few feet long and pushed by two actors sporting the costumes and accents of their countrymen. The story was clever, the jokes were funny, and the performances were strong—especially that of the blond actress playing Viktoronov, whose accent was as dense as a frat boy in a Smirnoff-induced stupor.

Of course, if the shows and the atmosphere aren't enough to relax you, an extra $7 for a post-show swim (or a visit to the bar) might just do the trick. It's not the Hamptons, but an elevator trip up 10 floors beats being stuck in traffic on Long Island. Maybe all of those tourists currently flooding Times Square had it right all along.

Southern-Fried Justice

Advocates of musicals as a serious art form may well gnash their teeth over The People vs. Mona, which bills itself as "a musical mystery screwball comedy." Though that label suggests a daring, genre-busting piece, the show is no more than well-crafted, enticingly performed fluff with a score by the creator of Pump Boys and Dinettes, Jim Wann, and a book by him and Patricia Miller. As the stage directions indicate, "High energy, fast-paced. Laughter and applause are certainly high among the goals." If you want vengeful barbers, French barricades, and weighty issues, look elsewhere. "Why did Mona Mae Katt kill her husband C.C. only 10 hours after they were married?" is the question pressing on the residents of Tippo, Ga., and particularly on the court convened in the Frog Pad, the local juke joint, superbly designed by Travis McHale. Vinyl records and album covers dot the walls of the stage and auditorium; there's a jukebox in one corner; and various indicators of the sultry climate—a fly swatter, a "Honk If You Love Jesus" sticker—are interspersed among them.

Mona's lawyer is Jim Summerford, a blandly pleasant attorney (though energetically played by Richard Binder) who resembles a cross between Jon Lovett and Ken Berry, the blandly pleasant actor who starred in Mayberry R.F.D. The prosecutor is Summerford's starchy, suited fiancée, Mavis Frye (Karen Culp), who has either beaten him or plea-bargained all their legal encounters.

As the trial progresses, the plot encompasses the future of the Frog Pad, the oldest juke joint in Georgia. Developers in town want to tear it down and clear the waterway for riverboat gambling, and Mavis may be in league with them. But would she go so far as to put Mona behind bars to help developers get hold of the property? And is something blossoming between the defendant and her attorney?

The witnesses include musical-theater aficionado Officer Bell, who's given the square-jawed dimness of Dudley Do-Right by strapping actor David Jon Wilson; Blind Willy (Marcie Henderson), a street person whose nose for the scents wafting by the crime scene rivals the finest sommelier's; and Euple R. Pugh, a 96-year-old lecher and the town's leading citizen. (The bizarre name is a drawback, however: a hymn to him sounds as if the singers are garbling the lyrics.) Pugh is played by Omri Schein, a bantam actor who appears to have Bilbo Baggins's DNA and takes on multiple roles—he's also a touchy dentist and a smooth-tempered Indian immigrant—with comic relish.

Mariand Torres as Mona (née Ramona) is a sensational singer and brings a lot of likability to the part of the Latina defendant. (Nonetheless, occasional dialogue in Spanish is still distracting, even though it's a crucial point of Wann's story that he's talking about the New South—multicultural and forward-looking.) But she and Binder don't have much romantic chemistry.

Wann's music encompasses folk, twanging country, blues, and even a school song. The score is almost a musical résumé. The songs are tuneful and the lyrics pretty smart, and they're played with outstanding musicianship by the McGnats, the joint's resident band (Ritt Henn, Jason Chimonides, and Dan Bailey). Each of the performers gets a chance—some more than one—to shine in the numbers, which include "Lockdown Blues" (with a yodel) and "You Done Forgot Your Bible," a gospel number that shakes the rafters, thanks to Natalie Douglas.

Director Kate Middleton moves everything along briskly, and choreographer Jill Gorrie makes the most of the limited space, particularly in "A Real Defense," a late number in which the suspects echo their earlier words in flashback to sort out the guilty parties. Fluff this may be, but it's of such a high caliber that it easily meets the goal of sending the audience out with a sunny disposition.

Borges, Brontë, and Butoh

The source material for SoGoNo's new Art of Memory is a heady mix. In a single publicity-related paragraph, the company mentions Frances Yates's 1966 "The Art of Memory," Giulio Camillo's 16th-century "Memory Theater," Jorge Luis Borges's 1941 story "The Library of Babel," the Brothers Grimm, and Emily Brontë. Adding all this to the fact that the company draws heavily on the techniques and strategies of the Japanese dance form butoh undoubtedly risks alienating some potential audience members who might already be skeptical of a show about "four librarians trapped in a fantastical library" who "search for an exit and create elaborate physical games that explore memory and illusion."

I am happy to report that the result is as engaging as it is mystifying, and that the pleasures of watching SoGoNo perform are almost as multifaceted as the material that went into the performance. Art of Memory is dense without seeming ponderous, introspective without seeming self-indulgent, and funny without seeming snide.

Of course, because I am one of those people who found the publicity material enticing rather than off-putting, my recommendation might be considered suspect. My guest at the performance, however, was familiar with almost none of the source material, had read none of the publicity, and acknowledged having never seen any performance remotely like this one. All I told him about the show in advance was that it fell under the vague category of "experimental." Because he was so taken with Art of Memory, I feel comfortable recommending it not only to those who think a butoh-derived meditation on Camillo and Jorge Borges sounds like a great idea but also to those who don't know who either of those people is.

While the audience filtered into the theater, a librarian whose dark clothes contrasted starkly with her chalky white makeup scurried along a balcony above the stage, apparently performing a ritual of some kind, preparing the space for what was to come. As the show began, three more women appeared, these dressed in frilly white frocks out of a Victorian storybook. They danced, chanted, and read aloud, surrounded by columns of books. Occasionally the balcony librarian, a ringmaster of sorts, would introduce new elements to spur the games and dances of the three women onstage. She might initiate a story that required call and response, or she might toss books like grenades down onto the stage.

This is a sometimes inscrutable piece, but the fragments and layers have clear connections that make the whole feel cohesive and accessible. The stories presented, some live and some recorded, all center around forbidden knowledge and transgressed boundaries. Again and again, young women are punished for seeking knowledge, objects, and spaces that their parents, lovers, and husbands have forbidden them.

As events progress, third-person stories shift into first-person memories, blurring the line between memory and fiction and suggesting that they are often indistinguishable from one another. Were the fictions reflections of traumatic experiences? Were real-world resentments and eccentricities the result of emotional responses to archetypal stories?

What elevates all of this above the level of self-indulgent introspection and renders it disarmingly entertaining is the precision, passion, and artistry of the performers, designers, composers, and technicians. SoGoNo Artistic Director Tanya Calamoneri and her collaborators have gathered a great deal of material that clearly resonates for them personally. The decision to construct a piece about the creative act of memory does not come across as having been pretentious or presumptuous, but as the result of a quest for a very personal kind of insight.

What is it about these stories, these ideas, that captured their imaginations? Why did an image of the Brontë sisters trapped in Borges's library/universe seem so right? Rather than attempt a reductive response to these questions, SoGoNo has crafted an athletic, compact, and often hypnotic exploration of them, inviting audiences to engage with the material on their own terms and participate in the creation of new memories, even as they ponder the nature of those already recorded.

Street Scenes

Forget the fact that it is summer and not February. The Greenwich Village Follies might just be one of the purest, most beautiful valentines audiences will see anywhere all year. More showcase than show, Follies—now playing at Manhattan Theater Source as part of its Straight from the Source series this summer—is a lively salute to Village history and locales, including local haunts like Chumley's, the famed speakeasy. It is filled with musical numbers by co-creators Andrew Frank (who also directed) and Doug Silver. (The two based their idea on an original premise by Fran Kirmser.)

This revue covers important moments selected by Frank and Silver, in chronological order. First, a cast member will provide a brief historical recap, then the ensemble performs a song based on the event, starting with the colonization of Manhattan Island. Some of these numbers are quite serious; a highlight is "On Our Corner," a moving ballad that captures the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911 with a perspective that is more ethereal than melodramatic.

Others are surprisingly humorous, such as the rebellious chant repeated by those assaulted during the Stonewall riots of 1969, a series of violent confrontations between police and gay rights activists. Silver himself provides musical accompaniment on keyboards, while Eric Laufer provides percussion.

The four outstanding cast members—two men and two women—prove to be an irresistible combination. John-Andrew Morrison, the most dominant presence, has an ebullient personality that is perfect for audience interaction (which includes a trivia contest) and in many of the show's more comic moments. He also has a terrific, soulful voice. In one of the production's more surprising moments, he dramatizes a poem written by Village denizen Edna St. Vincent Millay ("The Dream") and delivers a stirring showstopper.

Charlie Parker, one of the two actresses, is also a strong presence. One of her funniest sketches is "Resist the Grid," a humorous account of how, in all parts of the city, only the West Village differs from New York's rectangular street-grid layout. Patti Goettlicher has a beautiful voice and a good comic edge, put on display in "NYU" and "Dildo," two of the show's more adult numbers.

Particularly impressive is the quartet's more low-key member, Guy Olivieri. He too has a great voice and subtle reactions. One standout sketch for him is "Splatter Me All Over," in which he plays Jackson Pollock, with Parker serving as his canvas. (Follies also spotlights Village local Sharon Fogarty as a guest performer.)

Frank and Silver could still tinker with their creation. A few of the numbers could be lifted out, including the similar "Smoke Smoke (Hey Man)" and "Peace Peace (Love Love)." They offer very little commentary, merely acknowledging the drug use and free love of the 60s, and make the show seem a little too reliant on chant numbers. I am sure Frank and Silver could choose another event or two from the Village's history to act out instead. Another sketch, "Potter's Field/The Tell-Tale Heart," doesn't really provide any new information about Edgar Allen Poe. Perhaps Frank and Silver could choose a different work of Poe's to celebrate the famed poet.

And yet these quibbles seem very petty in a show that does so much right. With two creators so passionate and four gifted performers leading the production, the only folly here would be to not catch this show.

Players' Wives

The view from the sidelines fascinates playwright Joel Shatzky. His promising, lucid Amahlia concerned a figuratively tortured U.S. ambassador to an unnamed South American dictatorship who lives vicariously through his ex-lover, a doomed dissident journalist from that country. In Girls of Summer, written in the 1980s and now running at Brooklyn's Impact Theater, Shatzky looks at major league baseball from the viewpoint of a trio of players' wives. In the play's most successful moments, the team wives recognize how their lives have been sidelined—by the ruthless sports industry in general and their individual husbands in particular. However, the play suffers from a sitcom-style flight from genuine conflict, repetitive jokes, and a lack of psychological realism.

Girls of Summer predates, I think, the ensemble-of-housewives TV genre (as exemplified by Desperate Housewives, The Housewives of Orange Country, and, in the U.K., Footballers' Wives), but it does not transcend it. I saw the show, upon the company's request, at a final dress rehearsal where a few elements were still being ironed out—one actor in the smallest role is partially on-book, but I was assured he will not be when the run begins. Still, the glitches that ruined the play for me will be retained, because they are in the script.

Shatzky's three graces of the sidelines are thinly drawn types. Gina Marino (Heidi Azaro) is married to the team's most valuable player. She is a frantically religious Italian-American who knows her husband Dom's every game better than any sportscaster, but is in obvious denial about his playing beyond the ball field. Mary Lou Davis (Jennifer Oleniczak) is a Southern belle, desperate for her daddy's withheld approval and married to the rookie player. She knows nothing about baseball and is initially the butt of jokes by Gina and milquetoast sidekick Toni Browning (Loren Karanfilian).

When Gina is visited at home by her husband's sleazy manager, "Shifty" Jack East (Tim Lewis), who inexplicably wants her approval of Dom's new contract, the women must learn to overcome their differences and first impressions. Unfortunately, the intermission begins with that conflict apparently solved, and the problems the characters will face next are only hinted at: they show little sense of imminent danger. This deflates the suspense that ought to captivate an audience until the house lights fade again.

In Act 2, things get even messier. There are new challenges to the players' fragile careers and to Gina's marriage, while Mary Lou still struggles to fit in among the cliques of team wives, and Toni starts considering that she should make a career for herself in case her husband loses his. These professional and personal conflicts are promising and could have been developed into compelling theater. But they are soon deflated by the sitcom-style insistence that everybody should hug, make up, and feel all better before the entertainment ends.

The most glaring example of that formula made me absolutely lose my ability to suspend disbelief. It is at the end of the play and is a revelation, so if you intend to see Girls of Summer, you might not want to read on. When it is revealed that one of the wives has been raped by another's husband, the rapist's wife not only is relieved that her friend did not betray her but later makes jokes about her husband's (the rapist's) small endowment. Her friend, the woman whom he raped, actually laughs at and elaborates upon this.

By bringing this conflict up very late in the game and smoothing it over so easily, the play misses another opportunity for genuine, psychologically realistic conflict. Azaro and Oleniczak are competent actresses, capable of naturalistic acting when the play demands it, but their laughter at this moment seems as robotic as those of the wives of a different community: Stepford. I understand that it is a grave thing for a critic to reveal any part of a play's denouement, but this one is so far out in left field, it sends the play mercilessly to the dugout.

In the program notes, Shatzky writes that, in writing Girls of Summer, he wanted to explore "how the wives of these sudden millionaires coped with ... husbands who had been told, since they were big enough to hit a ball or throw one, that they were gods." A fascinating, funny yet tragic play could be drawn from that premise. After all, when the Greek gods were egocentric rapists, the best of the ancient writers knocked them clean out of the sky. If Shatzky's Girls of Summer played that kind of hardball, he would be batting 1,000.

Future Shock

As imagined 100 years into the future, New York City is both eerily familiar and radically changed. Developers threaten luxury hotels on Ellis Island, it's not atypical to reach age 137, and people subsist on hummus and bottled water. Everything feels a bit more dangerous: school violence has crept into kindergartens, where students attack their teachers with knives, and the blasts of detonating explosives regularly rumble through the air. Against this churning, splintering backdrop, Ethan Lipton examines the lives of five roommates in his hypnotic new play, Goodbye April, Hello May. There are the requisite couplings and wacky comic misfires, but Friends this certainly isn't. In Lipton's reckoning, New Yorkers will forever be self-absorbed and neurotic individuals. Human vanity is timeless and ubiquitous, and this cautionary tale warns of the emotional wasteland that just might be its legacy.

In a tiny Coney Island apartment, these young adults struggle for survival and labor to make ends meet, like typical New Yorkers. By placing their story a century into the future, however, Lipton prompts us to examine these lives with an objectivity that produces startling revelations.

Fleeing a bad breakup, Irene arrives in the city from Cincinnati in search of a new life. She moves into the apartment that her sister Paula shares with three men: Tom, a moody painter/bartender who lives in a gloomy closet; Harry, a drug dealer desperate for a new job; and Frank, Paula's boyfriend, who teaches school and comes home with various student-inflicted injuries. (His ever-present wounds become a running sight gag throughout the show.)

Irene finds a job in public relations, where, she nonchalantly reveals, she must occasionally sleep with someone to make a deal. It soon becomes clear that every character operates on some level of emotional sterility. Although Frank pleads for affection from Paula, who works late hours as a physician, he later shrugs her off, loudly complaining to Harry about her stony personality. Even Irene's poignant story about the end of her former relationship, related with dazzling sensitivity by Kelly Mares, is a falsehood, an empty event dressed up to appear like something that matters.

Erratic explosions inexplicably interrupt the occasional conversation, but they are never referenced by the characters—apparently they have become so normalized that they don't warrant comment. After Paula is badly burned in a nearby blast, Irene still prattles on about the minutiae of her love life to her bandaged and immobilized sister.

It's hard to tell if these bleak personalities are the result of the environment or an all-consuming narcissism, but Lipton gives us the chance to puzzle it out in the second act, when Paula and Frank move to the country.

Listening to friends discuss the minuscule details of their lives eventually becomes tiresome, and Lipton's dialogue also hits the occasional sag and snag. Most of the time, however, he deftly moves between pockets of wit and brilliance—the pervasive despair is enlivened by his devilish sense of humor and highly developed ear for authentic-sounding patter, as in the following exchange between Frank and Paula:

Frank: I got us tickets to a baseball game.

Paula: Do you think we should not be together anymore?

Frank: [Pause.] I think we should stay together long enough to go to the baseball game.

The script is given an enormous boost by Patrick McNulty, whose slick direction locates the show's grace and momentum. It's further enhanced by the extraordinary talents of its cast, all of whom turn in extremely focused and compelling work.

Gibson Frazier is especially winning as the wry and wary Frank, and he delivers his deadpan lines with masterful comic timing. His riff on New York City disaffection is particularly excellent.

As the tentative newcomer, Mares expertly captures Irene's early fragility and continues to show us glimpses of that timidity even as her character becomes tougher and more inured to city living. "I used to dream about helping people," she says. "What do you dream about now?" Tom wonders. "Outsmarting them," she replies.

The starched, anesthetic design underscores the chilly emotional disconnect that drives these characters. Jo Winiarski (set) and G. Benjamin Swope (lighting) contribute a sleek kitchen anchored by an icy tile floor topped with a large, multisectional fluorescent light. Beneath the fuzzy lighting, we squint along with the characters to try to see things clearly.

Eben Levy's original music provides still more texture. Warm guitar chords wrestle with frosty, bouncy electronic sounds, creating layers of dissonance and complexity that percolate along with the plot.

In many ways, New York City seems to survive on such waves of dissonance. Although it's impossible to know what the city will look like in 100 years, here's hoping that Lipton's invention will inspire a few souls to dodge the emotional scouring he predicts.

The Office

Co-artistic directors Britney Burgess and Matthew Nichols founded Zootopia Theater Company with the belief that "art should remove the boundaries and reflect the human animal," and what better way to show a person's animalistic nature than to put him in competition with another. Television has thrived on the dramatic premise that when a group of people working toward a shared goal are forced to co-exist in a small space, an individual's worst instincts will always prevail. In James Rasheed's dynamic dark comedy Professional Skepticism, we meet four frighteningly ambitious accountants with their sights set on becoming a partner in a prestigious South Carolina firm.

Set designer Andrew Lu has given new meaning to the phrase "paper trail," creating a string of enlarged Xeroxed balance sheets spilling from a giant manila folder hanging from the ceiling and connecting to a paper collage covering the entire back wall of the theater. A calendar suspended from the ceiling by a string of paper clips counts down the days until a big audit is due for a major client and personal friend of the company.

An explosive, bitter senior accountant named Leo (Steve French) is overseeing this audit with his two-man team of newly hired staff accountants, Paul (Matthew Nichols) and Greg (Wesley Thorton). Leo has good reason to be bitter; both his underlings have passed the dreaded certified public accountant exam on their first try, whereas Leo has been struggling with the last section for some time. (So difficult is this test that accountants are given up to three years to pass it.) To cover up for his own insecurities, Leo is constantly trying to instill new ones in co-workers, ruining office morale and hindering work conditions.

Because Leo is high-strung, he drives his colleagues crazy, and the result is a group of paranoid, scheming, plotting characters, all of whom have been stripped of their likability. Senior accountant Margaret (Britney Burgess) comes off as the most sympathetic, being the only woman working in this male-dominated world, but even she has a manipulative side, using her sex to manipulate her drooling co-workers. Greg is sympathetic in the beginning for his attempts to bond with the office outcast, Paul, until his true reasons for doing so are revealed.

In his role as the company whipping boy, and his clueless, buffoonish nature (he's prone to bursting into silly little boogies when he thinks no one is watching), Paul has all the makings of a sympathetic character. But the story's moral center hinges on the fact that he is not. Professional Skepticism shows the ways in which intense competition can corrupt even the most unlikely of characters. Early in the audit, Paul shows no signs of being an aggressive, manipulative man, and yet those qualities exist inside of him, erupting like lava when he is pushed to his breaking point.

But although they are not likable, the characters are all extremely entertaining to watch and so over the top that you find yourself drawn to them and their outrageous, unapologetic attempts to destroy one another. Bridges are being burned left and right, each character becomes an island unto himself or herself, and all are trying desperately to deceive themselves into believing they are better off this way.

Still, the heaviest moment in Professional Skepticism is a character-driven scene near the story's climactic ending. All four accountants rush into their shared office after a major revelation threatens their livelihoods. After pointing fingers and hurling accusations in an earth-shattering screaming match, they wear themselves out and stand there, staring at one another, perhaps realizing for the first time how utterly alone they really are.

Freedom Sketcher

According to Oscar Wilde, "The best government for artists is no government at all." British playwright Howard Barker's No End of Blame investigates whether all institutions make artistic freedom impossible. Produced by the Potomac Theater Project at the Atlantic Theater 2, this series of "scenes of overcoming" follows a freedom-seeking political cartoonist across Europe and the 20th century. Bela "Vera" Veracek, transparently based on a real, Eastern European-born British cartoonist, Victor "Vicky" Weisz, searches doggedly for a place to work and publish in freedom. Written in 1981, the play seems hardly to have aged, given recent censorship controversies—over the murder of Russian journalist Anna Politskaya, the Danish cartoons depicting Muhammad, and, in Barker's Britain, Guardian cartoonist Steve Bell's drawing of an Israeli politician eating a baby. For example, Veracek is told he can't caricature Winston Churchill because Churchill is "a god."

Elsewhere, Barker uses Veracek to criticize the covert censorship that many artists believe is disguised as development and education programs. Veracek visibly cringes as a smiling Soviet censor's board promises "to help rescue artists from their bourgeois habits" because "all artists grow enormously when they share ideas."

No End of Blame is one of two mainstage plays presented by the Washington, D.C.-based Potomac Theater Project in this summer's New York season. It is directed by Richard Romagnoli, who also directed the company's 2006 D.C. production of No End of Blame starring acclaimed actor Paul Morelli. As Veracek, Alex Draper fills Morelli's shoes impressively. He presents a complex, self-contradictory character, most brash when he is also clearly most afraid.

As Veracek's friend and opposite, the art-schooled, line-toeing painter Grigor Gabor, Christopher Duva is mouselike in both his tone of voice and his body language. The 11 actors in the ensemble work cohesively, playing a staggering range of characters, and accents, with schizophrenic ease.

The set is dominated by a huge projection screen, on which we see Veracek's and Gabor's drawings. "Veracek's," which are really by cartoonist Gerald Scarfe, are bold, often physically distorted figures with deep shadows and striking chiaroscuro, often with tiny eyes and screaming mouths. "Gabor's" (by Clare Shenstone) are appropriately technically precise but soulless.

The costumes, designed by Catherine Vigne, are simple but serviceable. They suggest the play's many eras, from 1918 through the 1970s, without making it look like a period piece.

Veracek's personality, as opposed to his art, is a dated cliché of the artistic rebel. His first iconoclastic act is to attempt to rape a traumatized civilian woman whom Gabor is trying to draw. This foreshadows Veracek's confrontational cartoons and his search for a libertarian society with a truly free press. However, it is still the old Romantic genius, for whom individual expression and feeling are everything and non-artists don't much matter.

At some moments, the production seems to raise controversial points, then retreats into the safety of silence. In one World War II "Veracek" cartoon, a British soldier is being strangled by a fat, bald man with a thin black mustache and pound notes sprouting from his pockets. Not merely a critique of capitalism and war, this image is strongly suggestive of the "war profiteers" (often explicitly foreign and Jewish) that were the butt of British editorial cartoons dating back to World War I. Must a "free" press publish this in order to be truly free? The play does not broach those issues.

Still, No End of Blame makes the audience think. Reduced in his old age and exile to "painting by numbers," Gabor concedes that this is "difficult." In staging this ambitious and provocative play, Romagnoli and the Potomac Theater Project adamantly refuse to paint by numbers.

Police Story

At the beginning of Accidental Death of an Anarchist, Italian playwright Dario Fo's protest-farce, the right-wing policeman Bertozzo (Daniel Doohan) warns the audience that, this being a radical play, Fo will take every opportunity to make him and his colleagues look ridiculous. Fo delivers, and so does the company, My Fair Heathen, which is performing Gillian Hanna's updated and Americanized translation at the Kraine Theater. In a Milan precinct office, Bertozzo is cleaning up after the death of an anarchist who either committed suicide or accidentally fell from a fourth-floor window while being interrogated as a suspect in a bomb plot. Then the case is opened by the Maniac (Megan O'Leary), a 16-times-committed mental patient and brilliant improv actor who has been arrested and hauled in for impersonating a university professor.

The Maniac goes on to impersonate the judge and win control of the police force, and asks questions about the Anarchist's death that the police will not ask themselves. Ultimately, the Maniac's vigilante justice reaches its most extreme point, and he confronts the audience with a dreadful choice that will probably divide even the most idealistic of New York liberal audiences.

Fo mixes the horror with buffoonish comedy, and My Fair Heathen plays it with aplomb. The police consider the anarchists "usual suspects" while ignoring right wing and neo-Fascist crimes, and when they find that the anarchists are not in fact organized criminals, they claim that "their disorganization is a cunning facade."

As an oafish Constable, Matthew Wanders performs a dance of hysterical contortions when he gets his hand caught in a mousetrap, doesn't think to remove it, and waits for the senior Bertozzo to do so. When the Maniac coaxes a trio of cops into an impromptu yet perfect cover of the Bee Gees, it seems both effortlessly natural and completely bizarre.

As the Maniac, O'Leary is sufficiently maniacal, and delightfully hyper in contrast with the sluggish cops. Wanders's wacky facial expressions and Del Lewis's deliberately unfunny bullying as the Superintendent make those actors stand out in an already strong cast. As the straight man and sometime M.C. of the evening, Doohan's Bertozzo incites pity if not exactly empathy. As an investigative journalist, Gretchen Knapp contributes a sobering realism. The group slapstick moments are swift, slick, and zany, thanks to director Janet Bobcean's blocking.

In several meta-theatrical asides, the actors drop their roles and play themselves, arguing about the play's shape, delivery, and meaning despite the audience's presence. Someone blows not the Maniac's cover but that of the performer playing him, by declaring, "That woman is getting out of hand!" Even Fo himself does not escape the play's barbs, as O'Leary defends herself by calling the author "a sexist dinosaur," but "a brilliant sexist dinosaur."

A major difference between the Maniac and the bumbling policemen is that the Maniac can think for himself (or, perhaps, herself), asks good questions, and comes to his (or her) own conclusions about events and their meaning. The policemen lack reason, imagination, and courage. It is therefore odd that in one of the play's proscenium-breaking digressive asides, the Maniac explains to the audience, as a rote lesson, that the corruption in the Milan police office is also practiced by the Bush administration. To state this rather than allowing us to imagine and reason it out for ourselves is to treat us like idiots, or lemmings.

Overall, though, My Fair Heathen smoothly conjures "the laughter in the labyrinth" from Fo's scathing defenestration of his society's respectable bullies. The company's Anarchist is laugh-out-loud funny as well as chilling, and unfortunately speaks to our place and time as loudly and clearly as a cop car's siren.

Shakespeare, Dressed Down

Have you seen Shakespeare's Richard II? Not the one with the snarling, limping serial killer—that's Richard III. Richard II is about the king who thinks he can't be deposed because he was elected by God to start colonial wars and pay off his sniveling, conspiring, hypocritical cronies. Theater of the Expendable's production, retitled Dick 2, is a perfectly serviceable one. Expendable is a young company made up mostly of non-Equity performers who are recent college graduates, some with no professional credits, or none outside Expendable. Therefore, it's not surprising that there is a steep learning curve. Some of the actors gave wooden performances or looked bored while listening to the principals' speeches. Twice, an actor got a wrong start on a line, then backed up and said it again.

Despite this, Dick 2 showcases some promising talents. These include the oratorical, eloquent Jacob Ming-Trent as Richard II and the swaggering Alan McNaney as his nemesis Henry Bullingbrooke. As Richard's queen, Jennifer Lagasse is properly plaintive and argues against their separation with great pathos. The underutilized Raushannah Simmons, playing a few courtiers and a lady-in-waiting to the queen, shows some great facial reactions to overheard bad news and is always in character without ever upstaging the principals. John Forkner gives a vivid turn as a philosophical Gardener.