For many Americans, the height of the Jazz Age undoubtedly reached its apex in the Roaring Twenties; particularly, when the Harlem Renaissance had both black and white night owls of the country flocking to the neighborhood's mysterious speakeasies and smoky basement-level dens for some of the best live music New York City had to offer. However, for playwright John Attanas, the very new, percussive sounds of jazz was only just beginning to find its groove, as the country moved into the early 1950s. Such is the world of Attana's newest work, All Gone West.

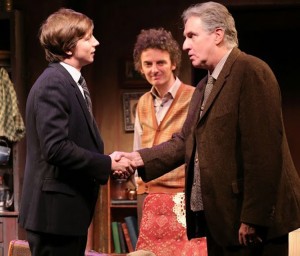

Set in post-war New York City, we meet Sam Samos (Joseph Robinson), a young and handsome war vet who learns about the fast-paced rhythms of the city—and of course jazz—from his fellow vet and black saxophone player Sonny Green (Jesse Means). Not long after settling in the city, Sam finds himself falling for Mary (Kristen French), a beautiful secretary at City College, whom he encounters one night when she walks into his bar with an older man, Joe (Glen Williamson), a professor at the college with alcoholic tendencies. They hit it off, and after Sam's persistence, Mary gives in and they begin a courtship, leaving Joe to his own devices.

The two lovebirds eventually marry despite their clear differences: Sam, an idealistic modern, is intent on one day opening his own jazz club, while Mary leans towards the conventional, with no high ambitions and generally happy with the lot she is given. These differences start to strain their marriage as Sam finally makes his dream come true, with the help of his friend Willie (Anthony Bosco), a fellow gambler whose questionable connections provides Sam's dream the financial help it needs. His club—christened The Blind Spot—starts off smoothly enough until Sam has trouble booking jazz acts that would draw crowds. He looks to Sonny, who by now has been approached with a record deal, but also has been nursing a drug addiction. As the bills start piling up, Sam desperately attempts to get by with some further help from Willie, as well as the hire of a prostitute (Kristen Booth). Ultimately, their business folds, and the two decide to follow the national pilgrimage West, where better—if only practical—prospects lay ahead.

Told in a magical realist-style, with the two lovers narrating between scenes, West's mood is evocative of the film noir genre that was popular during that era, and particularly called to mind films like Sweet Smell of Success and The Big Sleep. Just as the genre plays with contrasts, so does the thematic through-line of the play itself: the conventional versus the unconventional, new versus old. This is reflective not only in the fact that jazz inherently defies convention, but also in the differences between the characters—in particular, that of the ambitious Sam, and the content Mary. In their respective leading roles, both Robinson and French seem plucked straight out of the period. From the way Robinson's cool vibe to French's spot-on "New Yawk" accent, they embody stars of a bygone era. Cementing these solid performances were the supporting cast. Means' Sonny is confident and cool, yet belies a vulnerability. Another vulnerable portrayal was that of Williamson, whose alcoholic Joe displayed his weaknesses from the very beginning. Both characters each succumbed to their addictions, but their respective arcs are buoyed by the performances of both actors. Finally, Booth, whom perhaps had the most difficult task of the night, portraying multiple characters, also proved to be another strong presence onstage.

Also vital in setting the overall mood of the play was the presentation itself: the set designed by Andrew Diaz was naturally minimal in the modest performance space. Despite these limitations, the audience was nevertheless transported in time. Furnished by a simple brick wall structure, plastered onto which are various vintage posters, featuring advertisements for department store Gimbels and the Aqueduct racetrack. The use of various props—which include a dining table set and other pieces such as vintage glass soda bottles, newspapers and telephones—also help in differentiating between locales and situations. Nicholas Staigerwald's costumes added another dimension dressing the actors in various sartorial styles that were typically in vogue at the time, and worthy of any Modcloth shopper's envy today—particularly, a monochrome polka-dot one-piece bathing suit Mary dons towards the end. Of course, the element that perhaps had the most impact was the live jazz band, which brought to life the era in which the characters lived, and provided a romping soundtrack to the story.

A play about all kinds of losses—from the old to the new; the death of New York and the rise of the East Coast—All Gone West is certainly anything but your average show.

All Gone West ran from March 28 to April 18 at Teatro Circulo (64 East 4th St. between 2nd Ave. and Bowery). For more information on this production, visit the show's website: http://allgonewest.org/.