Two L-shaped, soot-blackened walls serve as the ominous backdrop of The Changeling, the first in a series of "scandalous" productions by Red Bull Theater this spring. One wall holds three glass cages, inhabited by the eerie denizens of an insane asylum, while the other is used for several lurid, thrilling acts (scenic design is by Marion Williams); cold-blooded murder and illicit sex come to mind. Director Jesse Berger's adaptation of the Jacobean tragicomedy has a great deal to work with, unsurprisingly. Aside from a few stiff moments, Berger's production steps up and delivers on the drama and suspense that is inherent in this scandalous work.

The story is a classical Spanish tragicomedy, written by 16th century playwrights Thomas Middleton and William Rowley (the former contributed to Shakespeare's Measure for Measure), and is rife with dark, morbid themes. Spanish noblewoman Beatrice-Joanna (Sara Topham) is being forced to marry Alonzo de Piracquo (John Skelley) by her deep-voiced, distinguished father Vermandero (Sam Tsoutsouvas), but she is in love with Alsemero (Christian Coulson). She is also the object of her servant, De Flores' (a fantastic Manoel Felciano) unyielding obsession. Joanna's calculative machinations to get rid of Alonzo come at the cost of her maidenhood—at the hands of De Flores himself, who yearns desperately for his mistress. Cover-ups, ploys and games of control ensue, while a subplot of similar yearnings and madness goes on in a nearby insane asylum.

The story is an admittedly noble, gory affair, characteristic of its Renaissance-Jacobean roots. The language is heightened and bombastic, as it should be. Red Bull Theater is one of the cherished few companies that has consistently produced acclaimed classical theater since its inception. In its opening scenes, The Changeling flags a little in its engagement—we briefly wonder at Alsemero's stiffness and Joanna's uncomfortable command of the stage. But such trifling missteps disappear, as the plot takes over and the actors fall into that cathartic rhythm of performance. Felciano, who plays De Flores, gives an especially intelligent performance, casting over his supposedly ugly character with a seductive poise and strange beauty. Tsoutsouvas' reverberating organ fills the stage, as does Topham's quick, shrewd movements.

Felciano and Topham, De Flores and Joanna respectively, have a terrifyingly potent chemistry. Even at the outset of their relationship, when Joanna despises De Flores for his malformed face and pathetic longing for her, each character stands on the brink of each other's sexual domains. Their interactions are fraught with an unhappy eroticism—she in the knowledge of her "taint" before marriage, and he in an impure passion of possessing his mistress, who does not requite his love. Their relationship is in quite beautiful contrast to that of Joanna and Alsemero; their love is an exercise in the age-old traditions of meeting, falling in love, and getting married. Coulson pours pure, handsome love into his character, while Felciano infects De Flores with a forbidden lust. They pivot around Topham possessively while she falls deeper and deeper into her Macbethian whirlpool of schemes.

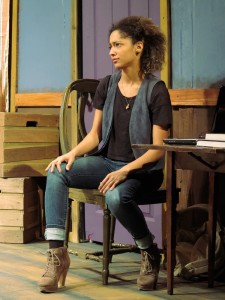

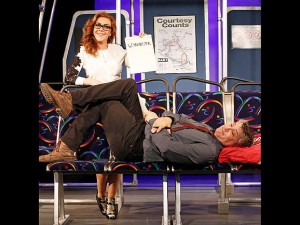

In a somewhat unrelated caper, the inmates of an insane asylum and their captors clash over the object of their affections: Isabella (Michelle Beck). This subplot seems a comedic aside at the beginning of the play, and tries to evolve into much the same problem that the main plot is beset with—three men who love and desperately wish to possess one woman. But for all its hilarity (and occasional bursts of choreography), the plot and its accompanying characters tie in loosely with the overall story, and does little besides. Beck dignifies her character with what little respect she is given by her lovers: her husband and man-in-charge at the asylum Alibius (a hilarious Christopher McCann), an airy, clown-like madman called Antonio (Bill Army) and an equally mad, love-struck poet named Franciscus (Philippe Bowgen). Army and Bowgen flit naturally between their mad selves and their in-love selves (the latter is an extraordinary madness).

The play does not deflate after its initial catharsis; rather, actors, sound, stage and light blaze in bursts of activity. Berger casts every aspect of his production in the same explosive mold—that of creeping scandal and abrupt action. The sounds that we hear are either soft and haunting or brief and very loud (sound and music design is by Ryan Rumery). The relaxed stupor that some audience members might fall into, especially after an abstracted soliloquy or post-intermission, is kept at bay. If the ears are not engaged (perhaps during a soliloquy), then one can't help but admire the flowing dresses, leather jackets and colorful doublets that move about the stage (costume design is by Beth Goldenberg). Besides its occasional lags and head-scratching moments, The Changeling is a a rare chance to see a sumptuously produced piece of classical theater.

Produced by Red Bull Theater, The Changeling runs until Jan. 24 at the Lucille Lortel Theatre (121 Christopher St. between Hudson and Bleecker Sts.) in Manhattan. Tickets range from $60-$80. To purchase tickets, call 212-352-3101 or visit www.redbulltheater.com.