Zero’s back in town, and the town is jollier for it. That’s Zero as in Mostel, in the ursine form of Jim Brochu, who has brought his one-man biographical show, Zero Hour, back to the Theatre at St. Clement’s. It won him a Drama Desk Award back in 2010, and in this new incarnation, if anything, the author and star is more formidable, more unpredictable, more voluble—more Zero.

He also resembles Mostel more than ever, to an almost scary degree. The time’s supposed to be 1977, near the end of the subject’s life, as he’s on the eve of rehearsal for The Merchant, a reworking of Shakespeare’s Shylock. Mostel’s in his sanctuary, a grimy artist’s studio, rendered with impressive detail by Josh Iacovelli (who also did the lighting, which is needlessly busy). This being one of those one-man shows that aims toward verisimilitude, it sets up a somewhat contrived premise—a Times reporter has come to interview him—allowing for a thorough compilation of all things Zero, punctuated by much awkward “What’s that you say? I’ll repeat it” interplay with the unseen guest.

This was an interesting life, one that touched on a number of important theatrical trends and genres of the 20th century. Born to a loving, crowded Jewish household in 1915, Mostel was blessed with a culture-loving mamaleh who encouraged his career in the arts, in economically unstable times; he survived, he said, largely thanks to the WPA. Loud and lumpy and ethnic, he wasn’t leading man material, but he was funny, and successful stand-up engagements at the likes of Café Society (at $400 a week, a fortune back then, opening for Billie Holiday) led to an MGM contract. A run-in with Louis B. Mayer canceled it almost immediately and led to most of his footage being snipped from Du Barry Was a Lady. By now he had happily married his second wife, Kate, a poised non-Jew who must have been a bottomless reserve of patience, headed back East, and taken up residence in what sounds like a dream of an apartment on West 45th Street. He did Broadway, mostly flops, some of which we hear about and some we don’t. The Mostels delighted in having open houses and throwing raucous parties. A couple of G-men turned up at one of them, leading to the Mostels’ darkest decade and the meat of Zero Hour.

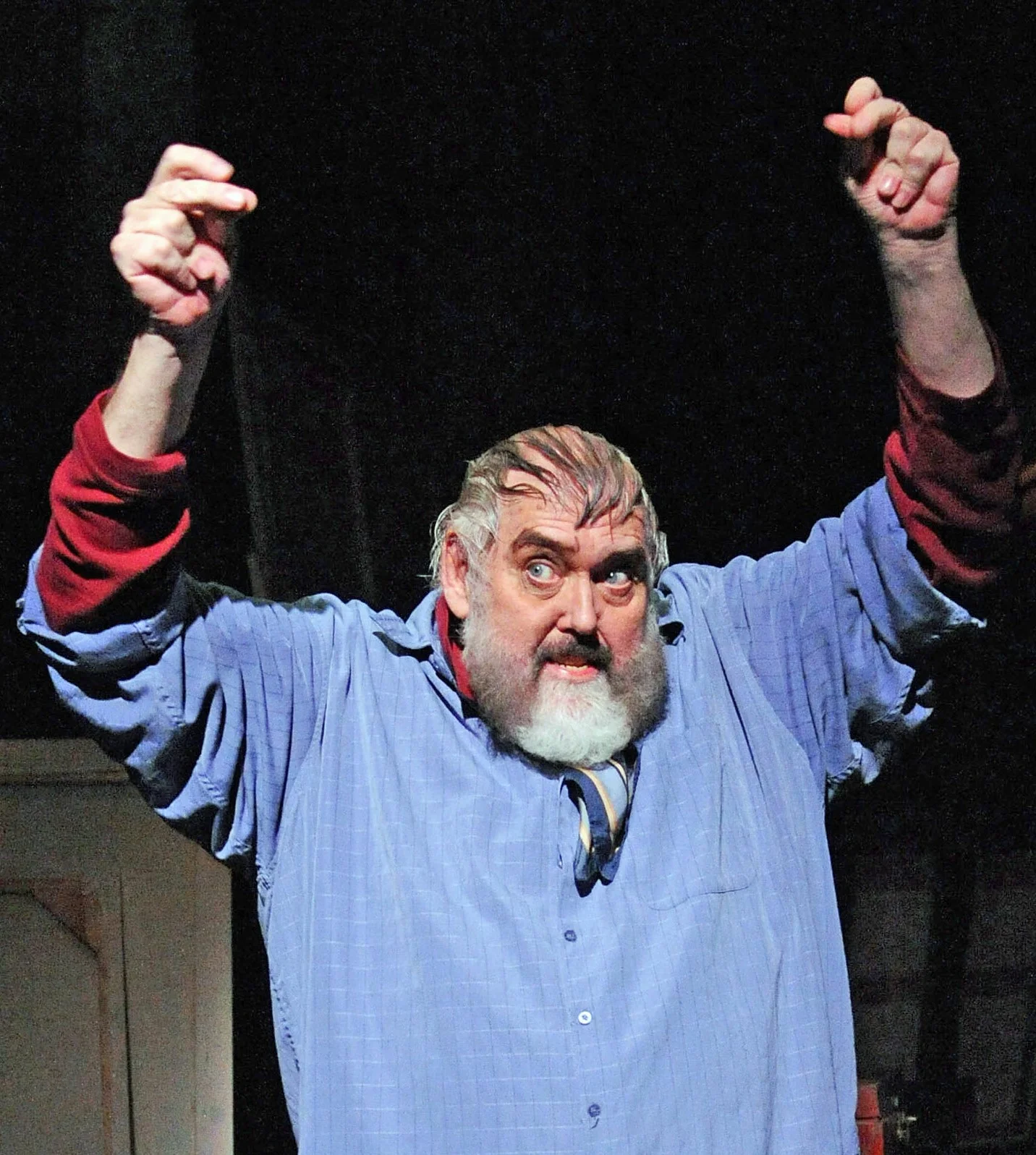

Jim Brochu (above and at top) plays actor Zero Mostel, star of Fiddler on the Roof and the film The Producers, in Zero Hour. Photographs by Stan Barouh.

Here we get a concise and evocative mini-history of the House Un-American Activities Committee, that red-baiting 1950s congressional scourge that detected a Communist under every mattress, treated witnesses without mercy, and bifurcated national opinion to a degree that may look familiar in 2017. Brochu arrestingly re-creates Mostel’s HUAC testimony, trying to joke his way out of it, invoking the Fifth, and seeing his career prospects get crushed as he faces the mic and primitive TV cameras. A major HUAC casualty was the Mostels’ good friend Philip Loeb, an actor whose blacklisting ruined his livelihood and led to suicide. Brochu’s expert here, too, combining Mostel’s concern for a pal with a really frightening anger, one that ruffled directors, producers, and fellow actors.

There’s a happy third act, as Mostel revitalizes his career, first with a Broadway flop (funny David Merrick story), then with an attention-getting off-Broadway turn in Ulysses in Nighttown, then a Tony-winning run in Rhinoceros that veteran theatergoers still recall with awe, then his two musical triumphs, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum and Fiddler on the Roof. The bête noire in these last two was director Jerome Robbins—“Loose Lips,” Mostel called him—who’d named names to the HUAC, and who, infuriatingly to Mostel, was a combination of utter moral depravity and utter theatrical genius. But the two men were able to collaborate harmoniously, for, as Mostel famously said, with apparent sincerity, “We of the left do not blacklist.”

Brochu doesn’t sound exactly like Mostel, but he sure looks and moves and intimidates like him, and when he bellows, which is often, catches his distinct timbre. Director Piper Laurie—who, interestingly, has her own connection to the HUAC, on the opposing side, as an ally of Joe McCarthy compatriot G. David Schine—entertainingly keeps him pacing and blustering and registering satisfaction when the audience laughs, which is also often.

Some intriguing contemporary names turn up along the way, in revealing anecdotes—Lucille Ball, Burgess Meredith, Ring Lardner Jr.—and they’re welcome diversions. Mostel, oversize in form and personality, isn’t easy to capture entirely in 90 minutes. He was unruly and frequently self-indulgent. As a teen, I caught him in a late Fiddler tour, which by then he’d turned into The Zero Mostel Comedy Hour—doing double takes and asides, milking every laugh, and striving to eradicate the great musical buried beneath all his shtick. The Zero in Zero Hour denies that side of him, insisting he respected authors’ intentions, and we’d like to know more about how the two sides of this mercurial personality coexisted.

We get only the briefest mention of The Producers, and none at all of The Front, a worthy 1970s blacklisting flick in which Mostel is quite brilliant. But Brochu’s probably exhausted by the end, and so are we. Communism, Marxism, Jew-goy relations, Tevye, oil painting, quips like “I have frozen food older than you are”—it’s a fully stuffed hour and a half. And a fun one.

The Peccadillo Theater Company's production of Zero Hour runs through July 9 at the Theatre at St. Clement’s (423 West 46th St., between Ninth and Tenth Avenues). Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. Thursdays through Saturdays. Matinees are at 3 p.m. Sundays. To purchase tickets ($49), call (866) 811-4111, or visit thepeccadillo.com, or the box office at the theater, up to one hour before performance.