Alan Palmer, the creator of the musical Chanteuse, appears in masculine attire in 1920s Berlin.

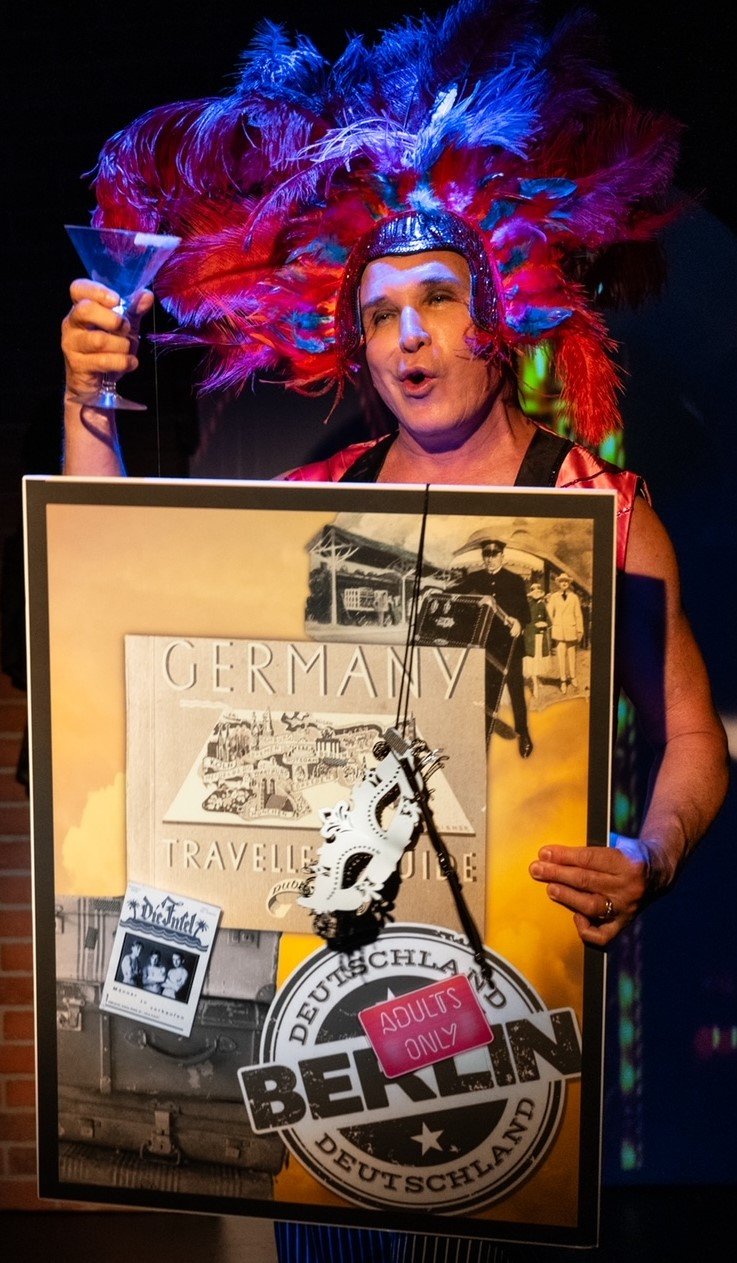

Werner adopts a drag queen persona in 1920s Berlin that eventually puts him at risk. Photographs by Russ Rowland.

If you just can’t wait for the transatlantic transfer of the hit West End Cabaret that was recently announced, cheer up, there’s another Nazi musical in town. That would be Chanteuse, the bleak and arresting solo tale of the remarkable fate of one gay man in Weimar and post-Weimar Germany. The performer, Alan Palmer, also wrote the book and lyrics, while the curiously soothing music is by David Legg. Chanteuse has a frightening and touching story to tell, but you might not be entirely on board with the way it gets told.

For much of its 70-minute running time, the show is firmly in Cabaret territory. It’s 1929 Berlin, where Werner (Palmer) is breathlessly relating the story of his life—singing a lot of it, in fact. Palmer’s lyrics are awfully on-the-nose and reportorial (“The end finally came of his boarding school strife / Time to make changes, get on with his life”), and Legg’s melodies, while traditional and pleasant enough, don’t do a lot to establish time or setting, or even mood; they’re just kind of Muzak-like, and the four-piece orchestra is recorded.

Anyhow, Werner, realizing at an early age that he’s not like the other boys, makes it out of boarding school and lights out for Berlin’s Schöneberg district, where things get interesting. Apparently the neighborhood boasted a lively and lascivious gay scene, which some uncredited projections helpfully illustrate. Palmer’s vernacular is disconcertingly present-day—“queer,” “trannies,” “butch dyke,” i.e., terminology that didn’t exist then—but it’s a beguiling moment in history, one we’d like to know more about. Werner becomes a drag chanteuse. (Bad sign: When he sings a gay, in the old-fashioned sense, little waltz, and urges us to sing along, nobody does.) He patterns his drag persona after his altogether delightful landlady, Frau Friedrich, who will become a surrogate mother and provide a devastating twist of fate.

For Frau Friedrich will soon unexpectedly expire, and Werner, wise to the encroaching rise of the Third Reich and bludgeoning of whatever rights minority Berliners had, will assume her identity. He has also fallen in love, with the bartender at his club, and, having pilfered Frau Friedrich’s passport and papers, the two are free to marry. Palmer will sing and sing most of this, and the lyrics won’t get any better: “Our love must stay secret when we are out on the street”—and why must it, if they’re masquerading as a straight couple?—“Yet once in our home we need not be discreet.”

The notorious 1934 purge called The Night of the Long Knives occurs, and suffice it to say, it isn’t pretty. Inconsistencies and narrative gaps pop up: The handsome Aryan soldier who’s paying “Frau Friedrich” attention—might he be closeted and aware of the deception? One minute yes, the next minute no. When Werner is standing in line at Sachsenhausen and about to be stripped, what on earth does he feel? And is a gas chamber a fit place for a song?

Jessa Orr’s set and Kathy Price’s costumes are competent. The sound effects, quite effective, are by Joe Doran. Palmer plays Werner with commitment and consistency, and, refreshingly, he’s unmiked. There’s not, however, a great deal of range: when he’s happy in Schöneberg, he’s fey and flamboyant; when he’s miserable at Sachsenhausen, he crumples to the ground, and director Dorothy Danner hasn’t coached much in-between out of him.

Plausible and affecting as the story is, it’s not, evidently, true, but a composite imagined by Palmer out of some concentration camp photos he saw that is intended as a commentary on homophobia’s rise, fall (did it ever, truly?), and resurgence. For anyone who has been following the criminalization of homosexuality in several African nations and the anti-trans and anti-nonbinary bills now clogging Congress, the SS atrocities displayed here will surely resonate, and hopefully rouse a staring-at-its-cellphones gay community to active protest. But earnest and well-intentioned as Chanteuse is, one can’t help wondering if a one-man mini-musical was the best format, especially with these prosaic songs. An I Am My Own Wife–style monologue, maybe? A conventional drama with a cast of more than one—why not? But Werner looking back on a happier, dying era and recalling, “I remember the first time you held my hand / How warm you felt, how strong you felt, and I felt so grand”—there’s room for improvement there.

Palmer Productions/HERE Arts Center’s Chanteuse runs through July 30 at HERE Arts Center (145 Sixth Ave.). Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday; matinees are Saturday and Sunday at 2 p.m. For tickets and more information, visit https://ci.ovationtix.com/219/production/1163291.

Book and Lyrics: Alan Palmer

Music: David Legg

Direction: Dorothy Danner

Set Design: Jessa Orr

Lighting and Sound Design: Joe Doran