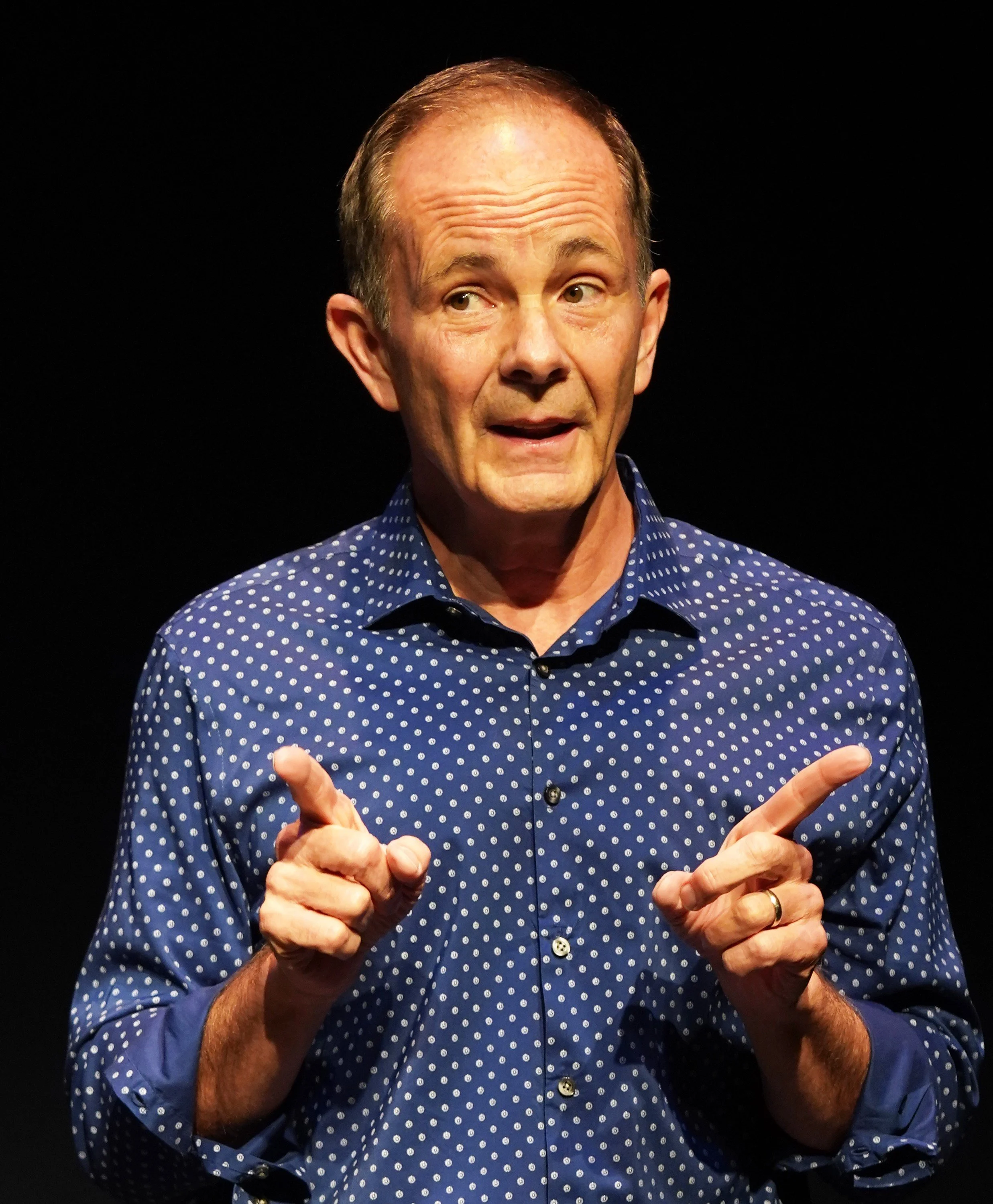

James Hindman addresses the audience during his one-man show What Doesn’t Kill You, which chronicles, among other things, his time spent in a New Jersey hospital recovering from a serious heart attack.

“Do you all eat grapes?” James Hindman asks, proffering a bowl of green grapes at the outset of his one-man show, What Doesn’t Kill You, directed by SuzAnne Barabas, artistic director of the New Jersey Repertory Company, where this show began its theatrical life. And while Hindman perhaps doesn’t want anyone to leap to their feet and grab a grape, this kind of seemingly non-rhetorical question is part of the audience intimacy he develops throughout the piece (and indeed some audience members did call out at various prompts, though no one took a grape). Hindman’s friendly, casual style establishes rapport, and once everyone is comfortable, he becomes a tour guide on his personal journey into and out of a New Jersey hospital, after suffering the kind of heart attack that one nurse refers to as the “widow maker.”

Hindman’s show began at the New Jersey Repertory Company and is now playing at 59E59.

But a widower it did not make out of John, Hindman’s husband, whom the audience meets via cell-phone photos projected onto a screen. This device allows Hindman to occasionally select the “wrong photo” for comedic effect, which also helps establish the faux-improvisational tone. The set, designed by Jessica Parks, consists of four chairs and a stool that Hindman moves around strategically to portray different settings, from a hospital bed to travels in Europe with John. Hindman can be whimsical and silly, relishing the occasional corniness of his jokes or prodding the audience to react in certain ways.

The show meanders pleasantly, with a humorous focus on the small indignities one must suffer as a guest of the U.S. health care system. There are new faces along the way, such as a Latina nurse whom Hindman dubs “Rita Moreno” and renders with an overly broad New York accent (he’s not particularly proficient at accents, as even he concedes when trying to mimic a tour guide in Prague). Other parodies, such as the hospital volunteer who offers him “tal-a-pie” (tilapia) in lieu of red meat, are more successful.

In fact, the show is so light that it’s a surprise when one of the two main threads to emerge (alongside Hindman’s time in the hospital) is a trip to a concentration camp (Terezin) with John. The anecdote begins humorously, recounting how John is the consummate traveler whose day must be filled with activities, whereas Hindman just wants to relax. Hindman ends up suggesting the concentration camp because it allows him to sit on a bus for several hours. In the camp museum he views drawings that were made by children from the camp:

I see a picture of an evil man putting a spell on a princess. I see dead bodies piled in a heap. I see a picture of butterflies. More butterflies. Flowers. I see faceless bodies flying to heaven. Mountains covered with trees and children playing, and children playing, and my body goes numb!

Hindman impersonates other people during his show, including nurses and hospital volunteers, as well as a tour guide on a trip to Prague. Photographs by Carol Rosegg.

He becomes fixated on the idea that the children had a teacher, and once he learns her identity, Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, he becomes fixated on the teacher herself: “Friedl taught those children to draw. To move toward the feelings, not away. To expose. To make something authentic from something so terrible.” She buried the drawings before she was transferred to Auschwitz, and they were discovered years later.

Hindman believes that Friedl’s story is one that people should know—and he’s right. The danger, however, lies in paralleling Friedl’s story with his own. Referring to his serious health scare, he tells his therapist about Friedl: “How I feel her betrayal. Your own country. To turn on you. To kill you. From the inside. Your own body.” Of his vow to overcome his fear and take a playwriting class, he says, “I met a teacher—my Friedl.” When his playwriting starts going well, he invokes Friedl’s students: “The children draw over 5,000 pictures. They draw. I write. They draw. I write.”

It is not to minimize Hindman’s heart attack and the obstacles he faced in recovery to point out that these stories don’t bear the same weight, and this creates a distracting incongruity in the show. Though it is well-intentioned, making the two narratives even vaguely analogous risks emotional confusion—it is meant to be life-affirming, I think, but feels naïve and almost distasteful.

That said, when Hindman is in his witty, theatrical comic mode, the piece feels cozy and intimate, and much of the 70 minutes spent in his company is pleasant, whether or not you have the courage to stand up and take a grape.

Jim Hindman’s What Doesn’t Kill You plays at 59E59 Theaters (59 E. 59th St.) through Nov. 3. Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday; matinees are at 2:30 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. For tickets and more information, visit 59e59.org.

Playwright: James Hindman

Director: SuzAnne Barabas

Scenic Design: Jessica Parks

Costume Design: Patricia E. Doherty

Lighting Design: Jill Nagle

Sound Design: Nick Simone