David Harrower’s elliptical two-character drama Good With People takes place in 24 hours in the Scottish town of Helensburgh (seemingly pronounced “Hillsborough”), a destination known for its tourism—it sits on a firth—and for local protests years before against Britain’s nuclear outfitting of a naval base there. The protagonists, innkeeper Helen and returning native Evan, embody both political and personal differences. Helen (Blythe Duff) has lived all her life in Helensburgh, and she recognizes Evan (Andrew Scott-Ramsay) as he checks into the hotel where she works; in childhood, Evan was among a group of bullies who humiliated her son Jack in an embarrassing, cruel incident. That wound has not healed, in spite of Evan’s apology at the time, partly because of social tensions between the families at the nuclear base, where Evan’s father worked, and the resident families. The townspeople looked down on the base families, in Evan’s estimation, and Helen resented the fact that Evan’s mother never said a word to her to indicate remorse over the bullying.

Now Evan has come back for the remarriage of his mother and father—they divorced and then got back together, a situation that somewhat parallels Evan’s departure for Pakistan, where he worked as a nurse for the Red Cross in Quetta, and his return to where he has roots.

The play touches on class issues and nuclear protests unique to British history that surely carry more weight with its native audience (references to Oddbins and the nuclear protests may be opaque to anyone who doesn’t know Britain and followed its politics). Harrower, in 55 minutes, delineates two lives in stark contrast. Evan’s rootlessness is a result of his parents’ moving around, and is reflected by their divorce and remarriage. As they flounder, so does he. In contrast, Helen is a fount of stability. Her son has benefited from her fierce loyalty; he has grown up, moved on and settled down with a girlfriend, and he carries no psychological scars. Although Helen is stern, she is not altogether unbending, and ultimate she finds sympathy for the young man she has resented for so long.

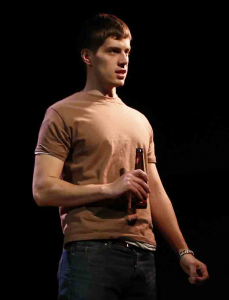

As slim as the story is, George Perrin’s staging turns it into a striking visual and aural experience. Using minimal scenery (by Ben Stones), he has created many memorable flourishes—there’s dancing, and at one point the strapping Scott-Ramsay upturns a bottle over his head, and sand pours out.

Harrower uses a cinematic structure, jump-cutting from scene to scene, as Helen and Evan meet at check-in and run into each other during the day and evening of the wedding. At one moment Evan is heading to the wedding; in the next scene he has returned. Tim Deiling has contributed stark film noir lighting, and Scott Twynholm, an intricate sound design (although the ever-present background drone of a bagpipe can become irritating to unaccustomed ears).

Gradually the ice thaws between the pair. Helen seems at times to become a surrogate mother, disapproving at first of Evan’s old behavior, but then slowly relating to him as an adult. Duff charts Helen’s attitudes from accusatory and condescending to motherly (she ties his tie for him before he leaves for the wedding), to curious and caring as a friend.

Scott-Ramsay is well-cast for his physique—one can believe the strapping actor would have had the stature as a teenager to bully a smaller child—but the actor also suggests a temperament held in check. Yet he also reveals the damage of his life. The Taliban captured him and made him eat earth—echoing the symbolism of the bottle of dirt, and his wanderings reflect a man who has not found himself.

The play specifically rebukes the British class system, which may not resonate with a foreign audience, but it carries enough weight for one to extrapolate the lesson that people are individuals and not cemented into the roles that popular attitudes may hold toward them. Harrower ultimately delivers an optimistic message: two people, separated by age, sex, political beliefs, personal prejudices, can still learn to become friends by talking together and trying to understand each other.