The Manhattan Theatre Club stage at City Center is giving off major Disney World Jungle Cruise vibes these days. Birds call over the syncopated groove of Nigerian percussionist Solomon Ilori’s 1963 deep cut “Tolani (African Love Song)” as patrons enter the theater. There’s a Tara Buddha statue downstage right, some Persian rugs, a scarlet chaise lounge and some cushions on the floor, and the proto-Afrobeat music morphs into the Middle Eastern goblet drums and chirpy marimba that have been cornerstones of “world music” for decades. It’s almost disappointing when no chipper, punning Adventureland employee pulls up to take you downriver.

Souls in Exile

Set in a dilapidated summer cabin in upstate New York, David Auburn’s engaging new play, Lost Lake, focuses on two people who might otherwise never have shared a stage. Yet Auburn, who won a Pulitzer Prize for Proof, develops a relationship between them that’s both believable and compelling. The result is a personal drama that resonates politically as well.

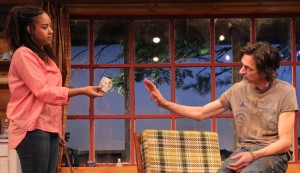

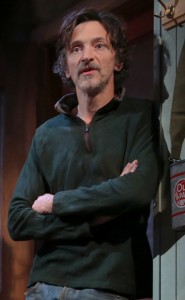

Veronica (Tracie Thoms) is a young black mother from New York City who, in the first scene, is negotiating the rent of a cabin for a week toward the end of summer. It’s March now, and Veronica has taken a bus to the cabin to inspect it personally and negotiate with the ostensible owner, Terry Hogan (John Hawkes). Hogan, shambling and pigeon-toed, is gregarious and optimistic but at times uncomfortably pushy, overselling the cabin (nicely detailed by J. Michael Griggs, with a broad upstage window and shabby plaid furniture). Yet Hogan also knows when he’s pushed too hard and needs to change the subject. But Veronica is no pushover, and Thoms invests her with the confidence and street smarts that make her unafraid to deal with Hogan.

When the summer week arrives, so does friction. Hogan hasn’t fixed the dock as he’d promised, and it’s rickety and dangerous for the children. He promised an extra bed; it’s not there. Worst, there’s no hot water. It’s a nightmare rental for Veronica, but Hogan tries to sell the bright side: “The kids are having a good time, right?” They bicker, and Auburn keeps one guessing where it’s all going. Daniel Sullivan’s superb production will make you want to stay along for the ride.

Sullivan deftly brings out the despair of these two lost souls. Their mistakes resonate with questions for the viewer. Is it possible to make a terrible mistake in one’s life and never be able to recover? Is there no chance for redemption? Hogan, it turns out, has a daughter from whom he is estranged, and a long record of failure. Veronica has a job that’s in jeopardy because of a mistake she has made, and is probably at the beginning of her decline. Auburn peels back layer after layer of their woes with astute dramatic timing. They are likable, flawed people trapped in limbo by their mistakes. The lake, a symbol of a carefree, pleasure-filled life, has been lost to them, perhaps forever.