Nat Turner seems to be the historical figure of the moment. He is the subject of the controversial film The Birth of a Nation as well as Nathan Alan Davis’s new play Nat Turner in Jerusalem. Whether the two works mark a resurgence of interest in Turner—William Styron won a Pulitzer Prize back in 1967 for his novel about the slave who led a bloody rebellion, The Confessions of Nat Turner—is uncertain. Davis has a narrower focus: the last night Turner spent in jail, as he receives alternating visits from his prison guard and the chronicler of his deeds, Thomas Gray.

Working with a small canvas—only two actors, one of whom plays two roles—Davis paints a portrait of a prophet of sorts. (The Biblical overtone suggested by the title is appropriate to the play, although the Jerusalem was in Virginia, where Turner was hanged.) Davis’s protagonist is a generally mild-mannered former preacher, as the historical Turner was; he had been taught to read the Bible, but not allowed to read anything else. He became a pastor to the slaves, and a leader. During a monthlong uprising that he led beginning in August 1831, he managed to enlist other slaves to his cause, and they killed 12 men, 19 women and 24 children. Davis makes it clear that the deaths of the last were horrifying and inexcusable—one child was thrown headless into a fireplace to burn.

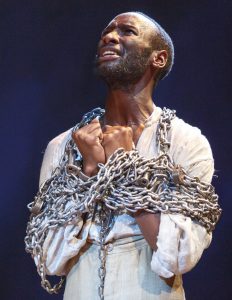

In spite of Davis’s early forthrightness about the horrors Turner perpetrated, the character, played with passion and philosophical nuance by Phillip James Brannon, gradually emerges as something of an Old Testament prophet of vengeance, imbued with a righteousness that some may find uncomfortable. It is perhaps the only way Turner’s story can be made understandable and receive any feeling akin to empathy, but it’s a subtle canonization at odds with his butchery.

There are intimations of the New Testament as well, as if Turner is also Christ-like. His chronicler Thomas Gray, whom Turner calls “Doubting Thomas,” refers to an episode “wherein you claim…to have spent thirty days alone in the wilderness.” The dual-edged reference is to Turner’s escaping capture for a month as much as to Christ’s 30 days in the wilderness. The Guard (Rowan Vickers plays both, but fares better as the Guard) shares bread with Turner. And echoes of Peter denying Christ arise in the Guard’s attempt to backpedal from a commitment he made to attend Turner’s hanging so the prisoner will spy a friendly face. (Davis’s notion that blacks will attend the hanging is a miscalculation, surely; given the recent slaughter of blacks in retaliation, it’s a stretch to believe they would gather at the gallows or that the white populace would permit them to assemble at such an incendiary event.)

The duologues Davis has devised between Turner and his two visitors are engaging and often eloquent. Turner declares, “It is Negro women, servants in wealthy houses who feed and nurture children like your daughter. Women whose own children may be snatched from them at any time and sent God knows where.”

Yet occasional moments ring false. Gray, considering a whale-oil lamp, says he feels “melancholy for the whales.... Sometimes I worry that there’s a limit. That one day there won’t be any whales left.” The sentiment might have been lifted from a recent Sierra Club press release on global warming. An example of Turner’s wit is also awkward. “Few men aspire to be the guards of prisoners,” he tells Gray in reporting a conversation with his guard. “It is little better than being a prisoner oneself. I said to one of the guards the other day, ‘Which one of us is on the wrong side of the bars? Which one of us is the real captive?’” It’s a sentiment that might be drawn from 1960s movies like King of Hearts or Cool Hand Luke.

Credibility aside, the production by Megan Sandberg-Zakian is deftly pared down and engaging, and Davis’s poetic language is given full weight. The only décor of the play, which is staged in traverse, is two large abstract paintings in gray and black, with hints of dull yellow and blue, and a platform that moves, scene by scene, from one side of the central stage to the other (the scenic design is by Susan Zeeman Rogers). An irritating loud-rock score (sound is by Nathan Leigh), akin to the pounding noise Neil LaBute used in The Shape of Things (2001), will drive you batty if you arrive too early—that is to say, more than 30 seconds before the play begins. At least what follows is, with whatever flaws it has, much more palatable.

Nat Turner in Jerusalem runs through Oct. 16 at the New York Theatre Workshop (79 E. 4th St.). Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Tuesday, Wednesday and Sunday; and at 8 p.m. Thursday, Friday and Saturday. Matinee performances are at 2 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. Tickets cost $69. Tickets may be purchased by calling 212-460-5475 or visiting nytw.org.