In the revival of Crystal Skillman’s Open, now playing under the deft direction of Jessi D. Hill, Megan Hill delivers a mesmerizing solo performance as the Magician—a woman who attempts to conjure the truth of a personal tragedy through the language of illusion. What unfolds is not merely a magic show, but a deeply felt meditation on love, loss, and the fragile hope that words—and maybe even spells—can undo the past.

birthday birthday birthday

Johnny G. Lloyd’s birthday birthday birthday follows a group of friends throughout the years as they celebrate milestone birthdays that two in their group share. The play begins as Marissa (Portland Thomas) and Clark (Justin Ahdoot) gather for their 21st-birthday party with their friends amid conversations about class, race, sexuality, hopes and dreams—with a helping of drugs, fights, cheating and gossip.

The Wildly Inappropriate Poetry of Arthur Greenleaf Holmes

Some people, as students or adults, hear the word “poetry” and run in the other direction. They’re that intimidated, bored, puzzled or whatever by it. Gordon Boudreau obviously understands this, as he has condensed the history of poetry to major highlights and demonstrates just how irreverent and free-spirited one can be with verse in his solo show The Wildly Inappropriate Poetry of Arthur Greenleaf Holmes.

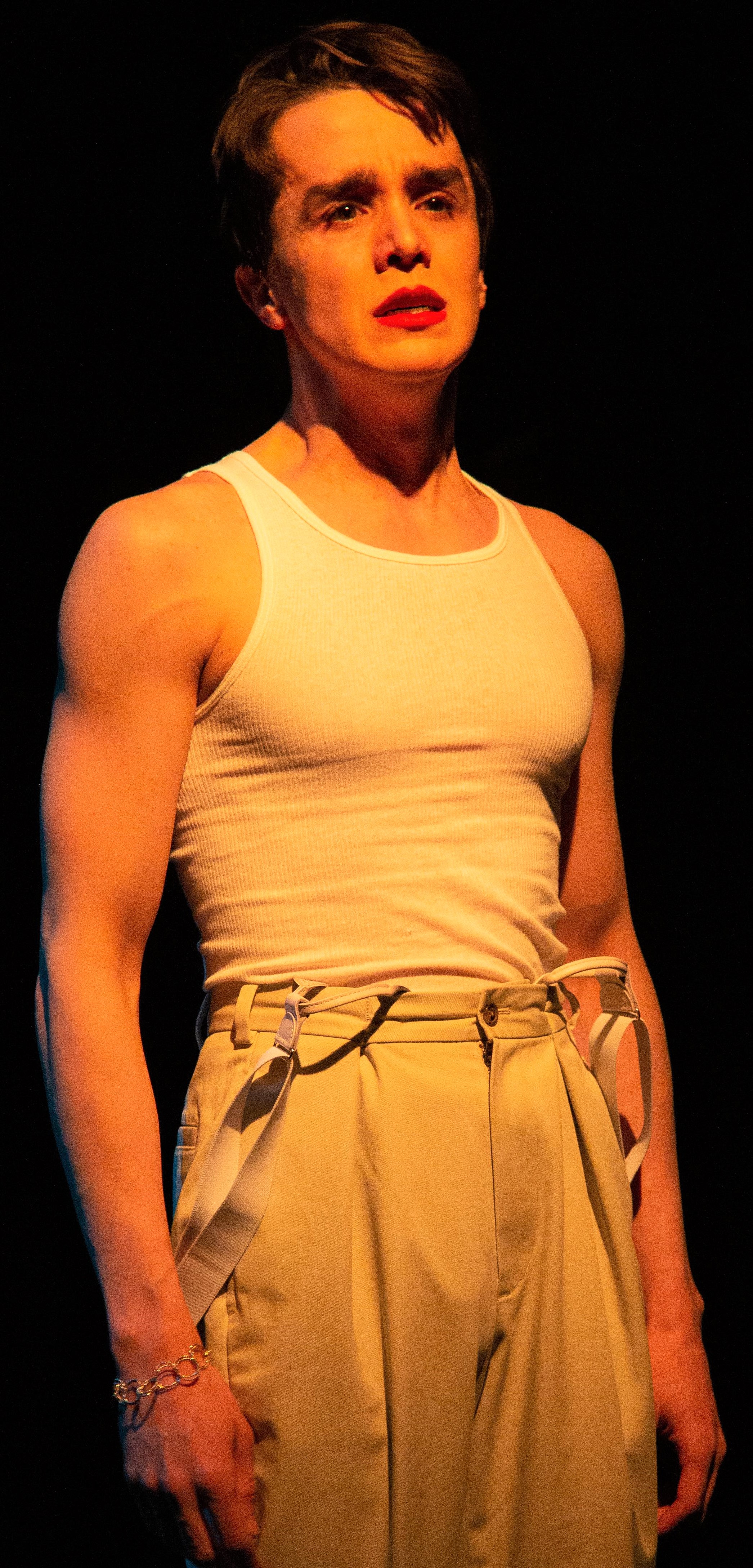

BrandoCapote

The setting of BrandoCapote, the multimedia performance piece currently playing at the Tank, is a room at the Miyako Hotel in Kyoto, Japan. It is the location in which Truman Capote interviewed Marlon Brando in 1957 when the star was filming Sayonara. The play hopscotches from 1957 to 2004, the year Brando died, and the hotel also represents, as the program explains, purgatory.

Real

The simply and ironically titled Real takes place in two time periods, New York in the present day and in 1934. The shift between them calls to mind one of Alan Ayckbourn’s time-travel plays, but playwright Rodrigo Nogueira’s voice is completely different. In the opening scene, a woman named Dominique (Rebecca Gibel), a retired concert performer, is hosting a dinner party with her husband (Charlie Pollock), who has revealed to the couple who have joined them that Dominique is practicing again.

The guests, Dominique’s best friend (Gabriela Garcia) and her husband, a professor (Keith Reddin plays the Polonius-like character, knowledgeable but loquacious, with an emphasis on irritating blather rather than comedy), are astonished. But it’s symptomatic of Nogueira’s obliqueness that one never learns just what instrument it is that Dominique plays, although composer Quentin Chiappetta has provided lovely music for a chamber trio (violin, viola, cello) that is integral to the plot and that one hears periodically and at length. The central conceit of the play is that the fugal form of the music introduces a main theme and then another joins it, and, by the end, the second theme has become the primary one, and the initial theme is subordinate; it connects easily to the work on display.

Darwin Del Fabro plays Dominic, a struggling composer in 1934, in Rodrigo Nogueira’s Real. Top, from left: Gabriela Garcia, Rebecca Gibel and Keith Reddin.

Dominique has become obsessed with a play she’s reading, and it’s actually a passage about that play, and its historical basis, that provides the most startling moment in Nogueira’s 70-minute drama.

Dominique: It’s about a young artist. An immigrant, actually, who lived here in the 1930’s, during the Mexican Repatriation.

Best friend’s husband: “Mexican Repatriation”?

Dominique: I didn’t know about this either. It was part of the plan to save the country from the Depression: mass deportations based on whether or not a person looked Mexican. … One million people were forced to leave. Most of them birthright citizens.

Best friend’s husband: How come I never heard of that?

Dominique: Because we tend rewrite history to create good memories that never existed.

At the end of the first scene, Dominique, with a bend and a heave of her chest, as if she’s having a heart attack or about to cough up an alien, becomes this young male artist, who is a composer named Dominic (Darwin Del Fabro), living in 1934. Thereafter the scenes alternate between Dominique and Dominic, marked out by music.

The actors in the modern segment portray ones in the earlier era as well, but the only characters to whom Nogueira has assigned names are Dominic and Dominique. Perhaps it’s his intention to show that the artist stands isolated from others no matter when he or she lives. Both Dominique and Dominic struggle with family obligations that hinder or interrupt their work, but there’s also a good deal of the story that is frustratingly uncertain. The chief allies in Dominic’s life are a maid (Garcia), who is a friend, and a second professor, who is a mentor (Reddin again). It is this professor who may provide a clue to Nogueira’s point: “Something is always happening to us. What is life but an interminable series of happenings? Or better, one never-ending happening.”

The key adversary in Dominic’s life is his overbearing father, and, under Erin Ortman’s direction, the brutishness that Pollock conveys as the father is more overt than that of the husband, whose flashes of temper are enough for the brawny actor to indicate a bully. Dominic’s father wants his son to abandon composing and return to his control. He knows Dominic is gay—he finds him with lipstick on—and he means to stamp it out. There is a subtext here, too, of society’s mistreatment of both homosexuals and women as inferior beings whose struggle to become mainstream artists poses greater hurdles than heterosexuals face.

Reddin as a dinner guest (left) speaks with his host, Dominique’s husband (Charlie Pollock). Photographs by Miguel de Oliveira.

Gibel as Dominique has the trickiest part, since she seems at times to be oblivious to her surroundings, and she is often a cipher. She has scant maternal pride in her child, and her transformation into Dominic raises questions that Nogueira leaves up to interpretation. Is Dominic dreaming of the future—he seems to know of Dominique’s existence—or is each channeling the other’s personality, forward and backward in time? Is one story real and one imagined? Are both real? Or is the story, as the professor has noted, one “never-ending happening”?

If one does not come away with an answer, Real at least shows Nogueira’s gift for poetic lyricism, and the questions he raises linger. It’s not a straightforward piece of theater, but it’s often fascinating, and it’s refreshing to find a theatrical voice as iconoclastic as Nogueira’s.

The Tank’s production of Real runs through Jan. 20 at 312 W. 36th St., 1st Floor. Evening performances are at 8 p.m. Thursday through Saturday; matinees are at 4 p.m. Friday through Sunday. For tickets and information, call (212) 563-6269 or visit thetanknyc.org.

Leisure, Labor, Lust

Sara Farrington’s Leisure, Labor, Lust has interesting subject matter—the intersection of class divisions and sexual orientation in the early 20th century—that is rarely explored in American theater. As a subject, the intertwining of sexual desire across class lines underlay The Judas Kiss, David Hare’s 1998 play about Oscar Wilde, but unfortunately Farrington brings little new to the table except the persons on whom she has modeled her characters.

Rule of 7x7

With a whole host of traditional plays and musicals available to choose from, it is sometimes refreshing when theater artists in New York City experiment with form. Creator and producer Brett Epstein’s Rule of 7x7 is just that: an experiment in playwriting wherein seven playwrights each declare a “rule” that must be incorporated into each play. These rules range from a word, a line, or a specific stage direction. To intensify the process, the artists involved have just one month to mount these short plays from conception to performance.