The actor Dakin Matthews won a special Drama Desk award in 2003 when he adapted both parts of Shakespeare’s King Henry IV into a single, albeit lengthy, version produced at Lincoln Center. His edit allowed regional theaters to present the histories of Henry IV; his son Prince Hal; and the roguish Falstaff in one production, lessening the expense of mounting two separate ones. The adaptation removes lesser characters, such as Mouldy and Rumour in part 2, and trims extended metaphors and a lot of obscure Elizabethan humor. But the famous scenes and lines remain—“I am not only witty in myself, but the cause of wit in other men,” “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown,” “We have heard the chimes at midnight.”

We Are Your Robots

We Are Your Robots, composed and performed by Ethan Lipton, is the perfect answer to the question “What do humans want from their machines?” Directed by Leigh Silverman, this musical about artificial intelligence arrives at the Polonsky Shakespeare Center like a breath of fresh air.

Macbeth (An Undoing)

Theatergoers yearning to see a new spin on Macbeth need look no further than Zinnie Harris’s Macbeth (An Undoing). Written and directed by Harris, it is a feminist version of Shakespeare’s original that puts Lady Macbeth at its center. But while Harris succeeds in expanding Lady Macbeth’s presence in the story, ultimately the playwright is defeated in increasing the character’s agency, given Shakespeare’s clear-cut trajectory of the doomed Queen.

The Merchant of Venice

When most people think of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, it's Shylock who springs to mind, not the titular merchant. As a Jew in a Christian city-state, Shylock is an outsider; as a moneylender in an economy that reviles usury, he’s a pariah. Director Arin Arbus has chosen John Douglas Thompson, one of the most accomplished classical actors of his generation, as Shylock in her modern-dress production at Theatre for a New Audience (TFANA). Thompson, reportedly the first Black actor to play Shylock professionally in New York, finds music even in the most acidic passages of the Bard’s rhetoric; his nuanced performance explodes at crucial points, with moral indignation outstripping self-pity.

The Emperor

The Emperor, based on a book of interviews with elderly government employees in the court of Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, is every bit as intellectual a docudrama as it sounds, mostly lacking emotional engagement. It’s more like history presented with interspersed activity as window dressing. Those who attend are likely to do so because of actress Kathryn Hunter’s reputation rather than a burning desire to hear about Selassie, who died in 1975.

He Brought Her Heart Back in a Box

For the past half-century, Adrienne Kennedy has carved out a unique niche for herself in the American avant-garde. Her one-act plays, such as Funnyhouse of a Negro (1964), A Rat’s Mass (1966) and Ohio State Murders (1992), are dense with allusions to pop culture, especially the movies, and fascinated with European royalty. Though riffing on Shakespeare and Greek tragedy, they are often semi-autobiographical, animated by Kennedy’s experiences as a black woman in America but shaded by her time abroad in Ghana and London. Elliptical and surreal, they cut right to divisions and hypocrisies at the heart of American society. He Brought Her Heart Back in a Box, Kennedy’s first new play in a decade, may be her most narratively straightforward work yet, but even at a svelte 45 minutes it is no easily digestible scrap.

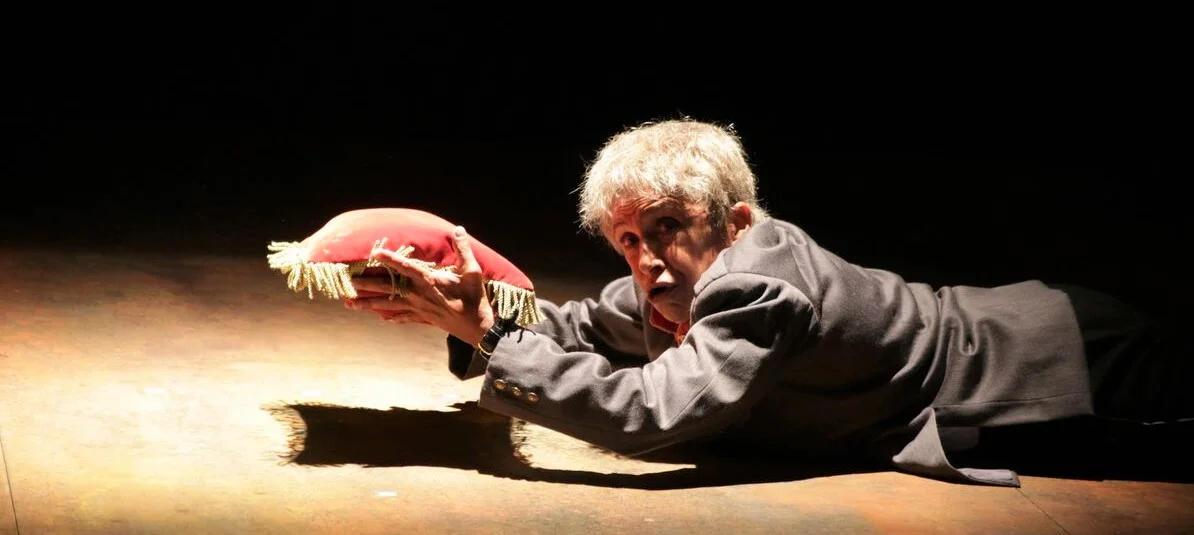

The Servant of Two Masters

There is much to laugh about in Theatre for a New Audience’s (TFANA) production of Carlo Goldoni's raucously entertaining farce The Servant of Two Masters, and boy, do we laugh. Every formula for comedy is either turned on its head or played to its full predictive hilarity. And when the unpredictable moments happen—this archetype of commedia dell'arte requires a fair amount of improvisation and ad-libbing—the risk of going off-script is richly rewarded. Sobering allusions to our current political theater, and maniacally incoherent strings of dialogue chock-full of anachronism, are rendered tolerable and even enjoyable under the guise of farce. Goldoni's capering plot still holds considerable sway over modern theater: Richard Bean's adaptation of this play, One Man, Two Guvnors, was acclaimed on Broadway in 2012 and made a star of James Corden. The genre possesses enough to buoy the weary theatergoer: ostentation, levity and music. But even endless entertainment has its limits, and Goldoni's 1746 story of cross-dressing sisters and miserly fathers hangs by a silken thread.

Shakespeare’s Game of Thrones

The first of Shakespeare’s quartet of late romances, Pericles (1608) is certainly one of the least known of his plays. Most scholars agree that the first two acts are by lesser light George Wilkins. Yet the production at Theatre for a New Audience is so engaging and visually sumptuous that one can only wonder it’s not a staple of the canon.

The opportunity to notch Pericles, the 35th of Shakespeare’s 37 plays that he has directed, has brought British director Trevor Nunn to Brooklyn. And Nunn’s genius in handling the notoriously corrupt text has pulled it all together, even though the main story splits into two and then three parts as the hapless Pericles endures loss and separation from his family.

Antioch is where Wilkins sets the plot in motion. There Christian Camargo’s prince, wooing the daughter of King Antiochus (Earl Baker Jr.), must solve a riddle to win her hand. Otherwise, his head may end up with others sitting atop cypress-draped spears. But the answer exposes a deadly secret, and Pericles flees the city. Unable to settle safely in Tyre, Pericles hands the reins to Helicanus (Philip Casnoff), his trusted adviser, and wanders around the Mediterranean. He has numerous setbacks and adventures, including marriage to Gia Crovatin’s elegant, demure Thaisa (a princess). They have a daughter, Marina, named by Pericles after Thaisa dies in childbirth, and he leaves her to be raised by friends as he heads to reclaim his throne. Betrayal and misfortune follow, and, believing Marina dead, he withdraws into misery. But, as Shakespeare turns a corner from his tragedies to the life-affirming romances, miracles do happen.

It all sounds pretty sappy, but it’s as spirited as Game of Thrones, what with jousts, shipwrecks and even pirates. Using gossamer, pleated tunics and gowns, costume designer Constance Hoffman creates distinct Levantine kingdoms: white for Pentapolis; black for Tarsus; indigo in Tyre; and in Mytilene, bright, Arabic-style clothes. The set by Robert Jones features an upstage wall with a large circle with panels that open to reveal varied terrains: a desert, perhaps, or, in a stunning coup de théâtre, a huge gray moon with the goddess Diana.

The story is based on a Renaissance novel by John Gower, who appears as the Chorus, eagerly spinning out the tale. Raphael Nash Thompson invests him with authority and sometimes a rich baritone, as he sings portions of the verse to an extensive score provided by Shaun Davey and played by 10 musicians from the PigPen Theatre Company, several of whom double in the small roles.

Nunn takes other liberties with the text, drawing on Wilkins’s 1608 novelization of the play for information to smooth out bumps. A nifty scene is interpolated when the surrogate Helicanus tries to quiet the demands of other lords for an explanation where their prince has gone, in front of a visitor that Helicanus suspects is an assassin. It’s a well-written scene, but it’s not from the play. One can sense Nunn’s sure hand in even the smallest details—when that same assassin, Oberon K.A. Adjepong’s Thaliard, arrives in Tyre, he looks around and says, “So this is Tyre, and this the court,” with a snort of disgust and an air of superiority.

For the most part, the actors handle the language with skill. Although Pericles is, like Job, more victim than agent of his destiny, Camargo speaks the verse confidently and is as heroic as the part allows, growing from callow youth to a man chastened by life’s hardships.

The more colorful roles are seized with relish. John Rothman as King Simonides is a merry monarch, trying to get his daughter, Thaisa, and Pericles to pair up. The strapping Ian Lassiter as Lysimachus, governor of Mytilene, starts off as a randy patron of the brothel where Marina is determined to keep her chastity and charts a touching transformation to her ally and eventual suitor. Will Swenson is a well-spoken Cleon, the starving King of Tarsus, whose life and country Pericles saves. Yet years later Cleon becomes morally hamstrung after his wife, Dionyza (Nina Hellman), plots Marina’s murder.

Not all is perfect. Patrice Johnson Chevannes as the Bawd misses a lot of the humor in the part. And the Marina of Lilly Englert is a major drawback. Englert radiates innocence and purity, but when she speaks, she sucks air audibly before every line and sometimes between phrases; the character sounds like she’s having an asthma attack. Her irritating aspirations mar some key moments, including the great reconciliation scene with Pericles.

On the whole, though, this rarely staged romance is a feast for the eyes and the ears, a gem from a master Shakespearean director that you won’t want to miss.

Trevor Nunn’s production of Pericles runs through April 10 at Theatre for a New Audience at the Polonsky Shakespeare Center (262 Ashland Place between Rockwell Place and Ashland Place) in Brooklyn. Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. on Tuesday-Saturday, and matinees are at 2 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. Tickets are $75-$85 and may be ordered by calling OvationTix at 866-811-4111.