The very first staging of The Weir at The Royal Court Theatre Upstairs in London shot to almost immediate acclaim, with nascent visionary playwright Conor McPherson winning a Laurence Olivier Award for Best New Play in 1997. Following incarnations of The Weir have starred current TV mainstays Brendan Coyle (of Downton Abbey fame) and Michelle Fairley (as a particularly aggrieved member of the Stark family in Game of Thrones). And The Weir does seem to require the same expressive vocal drama and expository storytelling that television shows afford us. With its extraordinary character appeal and its fascinating series of spine-chilling Irish folktales, the Irish Repertory Theatre's production of The Weir is a darkly bloodcurdling, utterly captivating take on McPherson’s well-crafted play.

Set in a rural Irish pub, bar owner Brendan (a serenely gruff Tim Ruddy) and friendly barflies Jim (John Keating), Jack (Paul O’Brien) and Finbar (Sean Gormley) try to welcome a lovely, mysterious import from Dublin, Valerie (an aptly cast Amanda Quaid), as she acclimates herself to her windy surroundings. The men proceed to tell haunting tales of faeries, poltergeists and abandoned houses, all the while struggling to reconcile their forced bachelorhood with their sudden, protective interest in Valerie—who has an eerie story of her own to tell.

Director Ciaran O’Reilly carefully fleshes out each character through the exquisite exposition of each individual story, courtesy of McPherson’s chillingly arresting words. Somehow, distinctly Irish turns of phrase possess an earthy accessibility under his pen, as well as a surprising amount of humor. There is an understated, rugged comradeship that the men share in their familiar curses and ubiquitous swigs of Guinness. The Irish flavor of it all is surpassingly delightful, as are the fantastical folktales borne out of that stout-and-song tradition; McPherson deftly paints his characters as traumatic products of their stories, and it’s difficult to distract yourself from their beguiling eeriness.

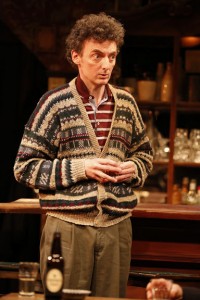

Valerie’s tale holds a deep, desperately weary grief. Jack’s dual yarns of a coldly enchanting faerie adventure and a haunting lost love both possess an expertly gleeful, then progressively sorrowful mannerism. Perhaps most harrowing are Jim and Finbar’s stories, for different reasons; an endearingly odd Keating imbues Jim with a trembling, wide-eyed respect for the supernatural, while Gormley’s Finbar is an uneasy skeptic, begrudgingly honest in his retelling of an eerie encounter, but steadfastly refusing to believe in anything out of the ordinary. But it is O’Brien’s gruff, garrulous take on Jack that gives the entire production that heady, hallucinatory magic. He keenly modulates the volume of his voice—whispering at climaxes and chuckling in practice disbelief—until it becomes an actor all its own. The back-from-hiatus (and excellent) Tim Ruddy makes us wonder why Brendan is still a bachelor.

Ciaran O’Reilly has woven each of these character’s stories with some unknowable alchemy. Even as a single actor seems to commandeer the stage with his or her tale, a magnificent change comes over their compatriots on stage: they become the audience. We are mirrored in their slack faces and uneasy composures; just as the seated audience writhes inwardly against our collective imaginations when Valerie narrates her ghostly tale, Jack, Jim, Brendan and Finbar cannot move. A magnificent design and sound/light team induce much of the trance-like state the audience enjoys.

Courtesy of scenic designer Charlie Corcoran, the bar room is a study in light and dark browns, cleverly synthesizing the homey, fire-crackling hearth ambiance perfect for storytelling. The lighting by Michael Gottlieb is an understated marvel dimming almost indiscernibly during the narrative sequences. During these instances, the audience hears a hollow, equally imperceptible whistling of wind, perhaps the most effective minimalist contribution to the play, overseen by Drew Levy. But the actors’ voices are so spellbinding that the whistling seems an organic soundtrack to their story.

The Weir ends much too quickly and the actors’ final exit leaves us with an irrational hope that they might come back on stage and tell us their hauntingly beautiful tales in their seductive Irish slang once more. Instead, we hear the familiar refrain of good luck, as Jack was accustomed to say before downing a pint, and the companionable reminder of the power of storytelling. In the end, when McPherson’s words have run out, we are left with a sweet, silent ache for some similar kind of chilling magic.

The Weir ran until Sept. 3 at The Irish Repertory Theatre at the DR2 Theatre (103 East 15th St. between Union Square East and Irving Pl.) in Manhattan. For more information, visit www.irishrep.org.