Two years ago, S. Asher Gelman made a splash with his first play, Afterglow, which examined a threesome of gay men. Scheduled to take advantage of Gay Pride month, it ran well over a year. Gelman’s second play, Safeword, has more challenging subject matter. The title comes from BDSM, which is, for those who haven’t read Fifty Shades of Grey, bondage and discipline (BD) and sadomasochism (SM).

Street Children

Pia Scala-Zankel’s 2014 play Street Children captures a small slice of life for gay and transgender kids on the streets, and features an ensemble of transgender, queer and gender-fluid actors. Set in the late 1980s around the West Side piers on the outskirts of the West Village, sex is currency in their milieu. When Jamie, played skillfully by Eve Lindley, arrives for the first time at the piers, her nose has been bloodied by a trick gone bad. She’s 17 and unschooled in this world yet she has nowhere else to go. Like all the kids who arrive here, she has been rejected by her family and society at large.

Boy vs. Girl vs. Boy

The hot-button issue of gender identity is at the center of Anna Ziegler’s Boy, a troubling and moving new play, and the first world premiere from the Keen Company since 2008. The subject of sexuality is in the zeitgeist, from a new musical, Southern Comfort, about Georgia transsexuals, currently at the Public Theater, to civic debates about restroom accommodations.

The story that Ziegler presents falls on the serious side. During circumcision, one of a set of twins was horribly mutilated, losing his penis. His distraught parents write to a doctor who appeared on 60 Minutes and specializes in gender identity to seek help. He advises them to raise the infant, named Samuel, as a girl, Samantha.

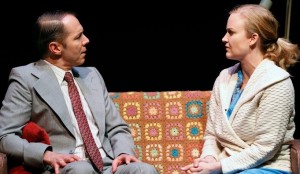

Ziegler tells her story in flashback, starting at the moment Adam, who was born Samuel but raised as Samantha and reinvented himself as a man, meets a girl named Jenny (Rebecca Rittenhouse) at a Halloween party. Jenny is someone Samantha knew in school and shared a class with. Jenny doesn’t recognize Adam, for obvious reasons, but he feels a strong attraction to her.

Bobby Steggert invests Adam with a mixture of well-meaning sweetness and a tentative confidence that sometimes leads him astray. His initial meeting with Jenny goes awry when she confesses having a 4-year-old child and he says he likes children and would be glad to give the kid a lift. It puts Jenny on guard, but it’s symptomatic of Adam’s failure to fully socialize himself. And, without using makeup or drag, Steggert gently creates a little girl, crossing his ankles or pitching his voice slightly higher, or talking quickly, as children do. The plan of Sam’s parents, Doug and Trudy (Ted Köch and Heidi Armbruster), is to socialize him as a girl until he is old enough to have operations to create a vagina. But even with Dr. Wendell Barnes’s coaching, Sam feels innately more interest in bugs, cars, and traditional “boy” interests.

The play comes down strongly in favor of nature prevailing over nurture. That brings it in line with the idea that being gay or transgender is not some perversion of the natural order. Indeed, the perversion in Boy is clearly the mentality of Dr. Barnes (Paul Niebanck), the eminence who persuades Doug and Trudy to maneuver Sam into the opposite sex. Sandra Goldmark’s unremarkable furniture nonetheless provides a striking visual parallel to the psychology: second sets of furnishings hang upside down over the set, a visual parallel to Samantha's inversion.

Even misguided, Niebanck’s doctor is a touching figure, a self-possessed gay man (he calls himself “a former boy who didn’t quite fit in”) who means to do well and cares in his way for Sam. Yet Niebanck invests the doctor with a sense that he is perhaps too doctrinaire in his theories. A climactic scene when Adam confronts Dr. Barnes and reveals that he has become a man, thanks to operations, is quietly devastating for both characters.

Ziegler plots the course carefully, and under the direction of Linsay Firman, the flashbacks make sense and flow smoothly. As in the playwright’s last outing, A Delicate Ship, which took its title from a W.H. Auden poem, literature plays a part. Here, Dr. Barnes’s assertion that Paradise Lost is the greatest poem ever written hints at a concealed interest in playing God.

Serving as counterpoint is another poem, Leigh Hunt’s Rondeau, which Dr. Barnes introduced to Sam, that remains Adam’s favorite. Milton’s is highbrow and concerned with the ineffable; Hunt’s is quotidian and concerned with real life and the physical, and ends: “Say I’m weary/Say I’m sad/Say that health and wealth have missed me/Say I’m growing old, but add/Jenny kissed me.”

Every so often Ziegler indulges in sentimentality, notably in a late scene when Adam reveals the night his father told him about the accident. Eating ice cream in the car, Doug said: “You came out of your mother, just who you are. This kind, gentle boy.” Steggert smiles affectionately. “You shouldn’t drink so much, Dad,” he says helpfully. And the anguished Doug replies, “I know that. But sometimes we just can’t control what it is we do, can we?” When the story is done, Jenny wants to know what flavor the ice cream was. It’s a clumsy non sequitur suffused with cutesiness. But the errors are few. Even if you’ve thought you’ve heard all the arguments about the topic, Boy brings them home powerfully.

The Keen Company production of Boy runs through April 9 at the Clurman Theater (410 W. 42nd St. between 9th and 10th Aves.) in Manhattan. Evening performances are at 7 p.m. on Tuesday-Thursday and 8 p.m. on Friday and Saturday. Matinees are at 2 p.m. on Saturday and 3 p.m. on Sunday. Tickets are $62.50 and may be ordered at www.telecharge.com.