“Remember that one Thanksgiving when your nearest and dearest sat down for a quiet game of Monopoly, but then your grandma got drunk and revealed a rich tradition of inbreeding? Well, tonight should be something like that…except with a lot more vodka.”

Yours Unfaithfully

Yours Unfaithfully, an unpublished, “un-romantic comedy” by Miles Malleson, gives its audience an intimate look at what it could be like to live in an open marriage, in 1933 and now. Mint Theater artistic director Jonathan Bank has unearthed Yours Unfaithfully and is presenting the world premiere.

Made in China

Made in China is a decidedly adult musical from Wakka Wakka, a New York–based theater company that prides itself on challenging “the boundaries of the imagination” with “bold, unique, and unpredictable” entertainments. This visually engaging production is performed by a host of black-veiled puppeteers manipulating intricately crafted bunraku-style puppets designed by Kirjan Waage. The script, by Waage and Gwendolyn Warnock (“with help from the Made in China Ensemble”), pushes the boundaries of puppet earthiness with a vengeance—it features puppet nudity, a puppet performing ordinarily private bodily functions, puppet copulation (both human and canine), and a puppet-dragon that has a mind-blowing digestive system.

The Beauty Queen of Leenane

Back in 1996, Martin McDonagh, a 25-year-old playwright, made a stunning debut with his play The Beauty Queen of Leenane, revitalizing that old war horse, the well-made play. Within a few years, he had several more successes under his belt: A Skull in Connemara and The Lonesome West joined Leenane to form a trilogy, not to mention his Aran Islands plays, The Cripple of Inishmaan and The Lieutenant of Inishmore (a third is still expected for a second trilogy).

This Day Forward

This Day Forward continues playwright Nicky Silver’s meditation on parent-child relationships that he made a success of with The Lyons. His caustic new play focuses on the damage that parents can inflict on children—it’s a broad canvas of emotional (and sometimes physical) abuse, distilled into two acts set a generation apart.

Othello: The Remix

As one of Shakespeare’s most famed tragedies, Othello has seen quite a number of adaptations over the years. The artistic duo Q Brothers take their stab at adapting this timeless play with Othello: The Remix, which discards Shakespeare’s original iambic pentameter in favor of modern rhyme set to rap music. In the spirit of Hamilton and other sung-through and hip-hop-infused musicals, Othello: The Remix is 80 minutes of fast-paced lyricism—spun live by cast member DJ Supernova and with hardly a breath in between. While there are a few questionable production choices, the massive amount of creative energy and impressive talent on display in Othello: The Remix make it hard to resist.

Sweet Charity

The musical Sweet Charity has good bloodlines—book by Neil Simon, music by Cy Coleman, lyrics by Dorothy Fields, original direction and choreography by Bob Fosse—yet the 1966 show has never occupied the top tier of musicals, such as My Fair Lady, South Pacific, Fiddler on the Roof or Gypsy. It has hardly languished in obscurity—there was a decent Broadway revival in 2005—but the New Group production directed by Leigh Silverman is such a persuasive delight that you may come away thinking it is top-tier after all. The production benefits from a terrific performance by Sutton Foster, a two-time Tony winner (and star of TV Land channel’s popular series Younger) in the title role. Foster is better known for big-budget Broadway shows such as Thoroughly Modern Millie and Anything Goes, but it’s a thrill to see her work magic in close quarters.

The Servant of Two Masters

There is much to laugh about in Theatre for a New Audience’s (TFANA) production of Carlo Goldoni's raucously entertaining farce The Servant of Two Masters, and boy, do we laugh. Every formula for comedy is either turned on its head or played to its full predictive hilarity. And when the unpredictable moments happen—this archetype of commedia dell'arte requires a fair amount of improvisation and ad-libbing—the risk of going off-script is richly rewarded. Sobering allusions to our current political theater, and maniacally incoherent strings of dialogue chock-full of anachronism, are rendered tolerable and even enjoyable under the guise of farce. Goldoni's capering plot still holds considerable sway over modern theater: Richard Bean's adaptation of this play, One Man, Two Guvnors, was acclaimed on Broadway in 2012 and made a star of James Corden. The genre possesses enough to buoy the weary theatergoer: ostentation, levity and music. But even endless entertainment has its limits, and Goldoni's 1746 story of cross-dressing sisters and miserly fathers hangs by a silken thread.

My Name Is Gideon: I’m Probably Going to Die, Eventually

Every now and then a theatrical experience comes around that breaks the mold. It’s no simple task to categorize Gideon Irving’s performance piece running at the Rattlestick Playwrights Theater. Part musical, part stand-up comedy, (very small) part magic act, and part intriguing night in a complete stranger’s living room, My Name Is Gideon: I’m Probably Going to Die, Eventually is far from a one-trick pony. On the contrary, the hour-and-45-minute show is constantly surprising audience members with laughs, gasps, songs and even snacks!

The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui

It’s a turning point in American history when a candidate for President suggests, ominously, that should the election not go his way, he will not go quietly into the good night of a peaceful transition of power. Bertolt Brecht’s sprawling farce The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui is a piercing look at the rise of a thug and petty tyrant whose lessons will not be lost on viewers in this election season. Written in a mere three weeks in 1941, the play is Brecht’s effort to radically deflate the mystique, worship, and awe that despots typically inspire. Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Minister of Propaganda, viewed his creation of the myth of the Führer as his greatest achievement, an achievement that made possible Adolf Hitler’s consolidation of power even as he was curtailing civil liberties and murdering real and perceived threats to his power. Brecht’s weapon of choice: humor!

Addictions of the City

The characters are lively, the language is crisp and urban, and the acting is skilled in Stephen Adly Guirgis's The Motherf**ker with the Hat. The energy of classic salsa music in the house helps pump up the energy at T. Schreiber Theatre’s exciting production. Guirgis’s unabashedly vulgar play explores themes of love, morality and choice in one of the most diverse cities in the world, New York. His characters, although primarily of Puerto Rican extraction, encompass the multiple ethnicities of the city. Most are plagued with addictions and afflictions that raises the stakes of their every move. The play, one of Guirgis’s best, is both hilarious and thought-provoking.

It starts with a high energy-conversation. Veronica (Viviana Valeria) is on the phone with her mother, who has an addiction to alcohol; Veronica dislikes her mother’s fish-faced boyfriend and tells her, “You’re dating a “fuckin’ big-time loser with a head like a actual fuckin’ fish! …Ma, when you see him tonight: Take a moment. Take a breath. Take a real good look and just ax yourself in all honesty—‘Do I wanna fuck him—or fry him up with a little adobo and paprika...?’”

Wrapped around the jokes and comic dialogue lies the issue of coping, or rather, surviving. Guirgis’s characters are struggling with heavy substance abuse and making it one day at a time. Each day is a journey for them. They include Jackie (Omar Bustamante) who enters with flowers in his hands and greets Veronica with enthusiasm and love. He chants a rhythmic “These flowers are for my Beautiful Boriqua Taino Mamacita Love Me Long Time Princess fuckin’ Beauty Queen.” Having just landed a job, Jackie wants to celebrate. He begins talking about their future, possible promotions—their life together. Still, Veronica is having trouble getting clean..

While Veronica takes a shower, Jackie finds a hat—a hat he knows does not belong to him. He smells the bed and pillows. He then asks Veronica, “Why the bed smell like Aqua Velva and dick?” But Veronica denies any infidelity and tries to calm him down by suggesting they go eat some pie. (That’s right, pie.) He reluctantly agrees.

Ralph D (Casey Braxton) is another one of the conflicted characters in the play. As a sponsor, he is guiding Jackie on the path to sobriety. Yet he is also the cause of Jackie’s fall. Ralph D has had an affair with Veronica while Jackie was in jail. Although Ralph D cares about Jackie, he has completely betrayed him. Ralph D has stayed “clean” from his additions, but he is not "clean" morally or ethically. Victoria (Jill Bianchini) and Jackie try as well, but inevitably fall off the wagon.

Among the charismatic, enigmatic characters is also Cousin Julio (Bobby Ramos). Julio helps Jackie hide a gun that he has used to threaten the man he thought was the owner of the hat. “Leave the gun. Take the empanadas,” he advises, in one of many comic lines. Julio is a delicious dichotomy of a character. Humorous and deep, he values family and is brutally honest, and Ramos’s performance is a crowd-pleaser.

Director Peter Jensen keeps the production’s energy high, and scenic designer Miguel Urbino uses sets that are minimal yet functional. They resemble an urban setting that captures the lives of these characters. Sound designer Andy Evan Cohen provides a taste of the urban Latino scene in New York City with salsa and hip-hop playing between scenes and during intermission—including “So Fresh and So Clean” by Outkast and classics by Hector Lavoe.

The Motherf**er with the Hat is a production you won't want to miss.

The Motherf**er with the Hat plays through Nov. 19 at T. Schreiber Theatre (151 W. 26th St.) Evening performances are at 8 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Nov. 9 and 16. Tickets are $20 for general admission; $30 for reserved seating; $40 for dinner plus VIP reserved seating. For more information, call (212) 352-3101 or visit tschreiber.org. The production contains graphic language.

The End of Days

Adam Bock’s rueful A Life covers both the title and its aftermath. It may borrow from—or perhaps merely echo—other plays, but in 80 minutes Bock conveys the fragility of mortality and the sadness of one person’s death in a deeply affecting way. Structurally, A Life is unusual. It begins with a long monologue, as David Hyde Pierce’s Nate, a middle-aged gay man, talks about his life, his ex-boyfriends, and his interest in astrology. The monologue lasts half an hour, and it may recall the tour de force that opens Tony Kushner’s Homebody/Kabul, although this monologue dovetails more organically into what follows.

Bock’s theme is virtually identical to that of A Delicate Ship (yet the result is more powerful), the Anna Ziegler drama staged by Playwrights Realm last season at Playwrights Horizons. That took its title from W.H. Auden’s poem Musée des Beaux Arts, as the Greek figure of Icarus falls from the sky into the ocean:

“The expensive delicate ship, that must have seen Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky, Had somewhere to get to, and sailed calmly on."

The point of Auden’s poem is Bock’s too: no matter the gravity of one person’s death, life continues in its myriad small ways, even though they pale next to the end of an existence. In the half-hour opener, Hyde Pierce is able to connect deftly to his audience with the details of Nate’s past. Obviously famous from his work on television, Hyde Pierce is a consummately skilled stage actor as well. He has a wry comic delivery, sometimes self-deprecating, sometimes bewildered, accompanied by nods of the head, hangdog eyes, pauses, repetitions and grimaces, as he relates his early life in Pawtucket, R.I.; his friendship there with a woman who got him interested in astrology; and the string of boyfriends that he has had, many of whose names rhymed: Sean, John, Ron, Johan, Jan. Every moment feels lived in and true.

Hyde Pierce’s casual yet powerful performance ensures that we come to care about Nate before his life-ending event. (Alas, it’s impossible to discuss this play without this spoiler.) Some of his friends, he says, wonder why he never paired up with Curtis (Brad Heberlee), his longtime best friend, but it’s not in the cards, Nate says. Their bond is conveyed in a lovely scene as the two friends sit on a New York City park bench and watch muscular men jog by, trading amusing expressions of admiration and frustration.

As Nate returns home, he suffers a heart attack. What follows under Anne Kauffman’s superb direction is another extraordinary bit of stagecraft. For perhaps four minutes—an eternity in stage time—nothing moves and one hears only Mikhail Fiksel’s urban soundscape outside and registers the subtle lighting by Matt Frey that indicates the passage of time.

Two scenes then pick up the thread of Bock and Auden’s theme more directly. The mortician’s office arrives to collect Nate’s body while the stricken Curtis stands by, a bit bewildered as the mortician, Jocelyn (Marinda Anderson), takes a call on her cell phone. It seems inappropriate, but it’s also true: other lives continue in all their small, messy ways even as one life ends. There are even comic moments amid the tragedy, as Jocelyn persistently mishears the phone number Curtis is trying to give her, and they go back and forth trying to get it right.

In the following scene the drama literally stops, as it does in D.H. Lawrence’s The Daughter-in-Law after the husband comes home from the mines and washes up, drawing its power from the simplicity of action. On a gurney in the funeral home, Nate’s body is prepared, as Jocelyn and her assistant comb the hair, cut the nails, and glue the lips shut—while discussing family flare-ups and inconsequential bits of botany and biology. The effect is to set in relief, amid the mundane babble, the gravity of a life lost.

Bock’s final scenes follow Nate’s funeral, Curtis’s breakdown (Heberlee’s part isn’t flashy, but he inhabits it feelingly), a speech by Nate’s sister (Lynne McCollough, who is equally good as a mousy mortician’s assistant), and a voice-over (there have been some already) from Nate. The voice-over carries the promise of something beyond. It’s a graceful and powerful ending to a simple story, brilliantly staged and presented.

Playwrights Horizons (416 West 42nd St. between Ninth and Tenth avenues) is presenting Adam Bock's A Life through Dec 4. Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays and at 7 p.m. on Sundays. Matinees are at 2:30 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. During Thanksgiving week (Nov. 21-27), the performance schedule will be Monday, Tuesday, Friday and Saturday at 7:30 p.m., and Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday at 2:30 p.m. Tickets are $59-$99 and may be purchased by phone at (212) 279-4200 or by visiting phnyc.org.

A Classic Comedy Conquest

Playwright Oliver Goldsmith found fame with his play She Stoops to Conquer in 1773, despite his rather unfashionable social reputation among London’s upper crust. Indeed, Goldsmith made it his life’s work to go against the grain, and She Stoops to Conquer exemplifies his disdain for Sentimental Comedy—a genre that was en vogue in the first part of the 18th century. Those saccharine works featured one-dimensional characters whose apotheosis was meant to instill what Sentimental playwright Richard Steele haughtily deemed “a joy too exquisite for laughter.”

Goldsmith, on the other hand, was a champion of hearty laughter, which this play—when produced well—can stir up in droves. Compared to Sentimental characters, Goldsmith’s characters are imperfect, and therein likable. The Actors Company Theatre (TACT) is staging a slightly imperfect (and therein quite likable) production of Goldsmith’s important play, directed and adapted by Scott Alan Evans. The moments when this production shines most are when it is faithful to Goldsmith’s unique genre of “laughing comedy,” aimed to elicit belly laughs with physical ridiculousness and silly twists of plot.

She Stoops to Conquer presents a bouquet of delightful characters—two eligible ingénues, a couple of bachelors from the city, and a pair of meddling parents—all of whom are subject to the playful deceits of the puckish Tony Lumpkin (Richard Thieriot). The action takes place at Mr. and Mrs. Hardcastle’s estate in the English countryside. Their daughter Kate (Mairin Lee) and their ward, Constance Neville (Justine Salata), are excited to receive two handsome young suitors (Charles Marlow and George Hastings, played by Jeremy Beck and Tony Roach) at the estate that evening.

Tony, who also happens to be Kate’s illegitimate brother, foils the plan when he intercepts the suitors at the village pub. Wanting to free himself of his mutually undesired betrothal to Constance, Tony concocts some of his signature meddling. Bringing the suitors to the estate, Tony leads them to believe that they are staying a night at an inn—and that the elder Hardcastles are actually innkeepers. This creates room for Kate, disguised as a barmaid, to woo the painfully shy Marlow, and for her cousin Constance to pursue her true love Hastings.

Overall, the cast seems to enjoy themselves in this genre. Thieriot as Tony absolutely sparkles with his mix of conniving wit and lowbrow buffoonery. As his bumbling parents, Cynthia Darlow and John Rothman are adorably befuddled by their son’s antics. Things really get good after intermission, in which Tony sends his enraged mother and Constance on a 40-mile carriage ride to nowhere, and Mr. Hardcastle finally snaps after being treated like the help in his own home. The two sets of young lovers deserve even more spice, however, especially in light of their comic counterparts; perhaps that could be created with more emphasis on physical humor rather than delivery of language.

One distinct aspect of this production is its intermittent puncturing of the fourth wall. Evans’s direction leans heavily on this device, employing a considerable amount of direct audience interaction and unmasking of the usual theatrical dressings. For example, there is no backdrop to hide the actors as they await their entrances. Instead, they are visibly seated in two rows of chairs on either side of the stage, which is a raised platform. Admittedly, Goldsmith's original script contains plenty of asides—monologues that characters deliver directly to the audience—but by stripping the stage bare, Evans’s adaptation carries the meta-theater several steps further. The bits of audience interaction between scenes undermine the actors’ comic choices and interrupt the flow and style of the play. All in all, however, this nontraditional choice does not sink the production, which provides both a fun night at the theater as well as an opportunity to experience one of England’s most important and beloved plays.

TACT’s She Stoops to Conquer plays at the Clurman Theatre at Theatre Row (410 West 42nd Street between Ninth and Tenth avenues) until Nov. 5. Tickets are available online here or by calling the TACT Member Hotline at (212) 560-2184 or (212) 947-8844.

One Man’s Treasure

As the saying goes, “One man’s trash is another man’s treasure.” So it is in Storage Locker, a black satire riffing on A&E’s reality show Storage Wars. Written by Jeff Stolzer, the play is often quite funny, with expressive banter between a husband and wife who secure the winning bid on an abandoned storage unit. Stolzer is a clever writer. In Storage Locker he develops interesting and layered characters, intricately weaving them into shifts in time. Bryn Packard and Nicole Betancourt, who play the husband and wife, deliver the dialogue with velocity of a couple that have been together for awhile. Stolzer easily takes them from ridiculing each other to playful and loving in a blink. Betancourt is smart and sassy, a diminutive “spitfire” to Packard’s “I’m the provider, I make the decisions” husband. They are believable and engaging.

Director Julián Mesri invests the script with a tempo that draws the audience in. With a video camera on a tripod and monitor, soon enough it becomes evident that the pieces of masking tape on the floor are marks to make sure the actors are in the sight line of the camera for television production. Reality television has little to do with reality, after all. Here, the audience is inventively caught between observing the actors on stage and through the monitor. Betancourt and Packard have a great time playing to the camera; their chemistry is contagious. Mesri’s use of the stage, including the sound booth and emergency stairwell, as well as video camera equipment, helps creates a comic romp through one man’s trash.

Also watching the monitor is an older man seated with his back to the audience. He fiddles with a Rubik’s Cube. In time, the older man (David Crommett) enters the fray, wanting to purchase the storage unit from the husband and wife. He claims he was late to the auction because of a doctor’s appointment. Crommett plays the character in the manner of a master manipulator. He toys with both the husband and wife, luring one with his tales of woe and the other with the wisdom he has developed over 30 years of choosing which storage units pay off. That might be a Picasso behind the trunk. Again, the fun of Mesri’s direction is watching the actors running to the sound booth as if to engage the television producers for direction or utilizing the camera as a handheld and chasing the old man.

Stolzer’s script, with an ample amount of intrigue, and Mesri’s keen staging keep everything moving smoothly until the last five minutes, when it all just sputters. Oddly, with everything that’s going for it, the play devolves at the very end into a confusing “fade to black” puddle. Even the actors, who until this point were spot on, appear lost. Throughout the play the storyline arches and pulls back, reels and sways, and then, suddenly, it’s as if someone lost the last two pages of the script—65 minutes of witticisms, laughter, cajoling, and get-rich-quick banter followed by five minutes of “What just happened?”

The set design by Warren Stiles looks all wrong, and a simple site visit to Gotham Mini Storage should have been required. Instead of a storage facility of cement hallways and orange metal roll-up doors, there is only black plastic sheeting, ragged at the bottom where it doesn’t come completely to the floor and light seeps under. Trash bags the characters pull from the storage unit that are supposedly filled with 50 pieces of clothing are kicked around as if they are filled with crumpled paper.

The lighting by Miguel Valderrama appears to toy with the otherworldly, in a Twilight Zone manner, but falls just a bit short. Most likely his efforts would have paid off with an appropriate set, but how does one light a misstep? Director Mesri put together an interesting original score, which included excerpts from Leos Janáček’s first and second string quartets.

Storage Locker is a perfect example of why small theaters are one of the best “play-grounds” for makers of theater. Playwrights get to test their writing skills, directors hone their craft, and actors perfect character development—all for the pleasure of the audience, which gets to bear witness to the creative process. For 65 minutes, or 92% of the time, Storage Locker and its quirky, delicious contents deliver.

Storage Locker can be seen at 8 p.m. Thursdays through Saturdays and at 3 p.m. Sundays through Oct. 30 at IATI Theater (64 East 4th St., between Bowery and Second Avenue). The running time is 70 minutes. Tickets are $30; students and seniors $25. For more information and to purchase tickets visit iatitheater.org/programs/detail/storagelocker.

Grin and Beer It!

A Brief History of Beerbegins, quite appropriately, by inviting the audience to drink beer. This is not an average toast, however, as the audience is encouraged to really taste the beer—exploring its effervescence, hoppiness, and temperature. Thus begins William Glenn and Trish Parry’s wacky journey through time and space to simultaneously delve into the origins of beer and save it from some unspecified nefarious threat. Despite the plot’s silliness, Glenn and Parry are charming to watch under Jeffrey Mayhew’s direction as they wholeheartedly commit to the ridiculousness of their show.

Living and Laughing Together

Fans of the hit television sitcom The Golden Girls can now experience Blanche (Cat Greenfield), Rose (Arlee Chadwick), Dorothy (Michael LaMasa) and Sophia (Emmanuelle Zeesman) all over again. But this time these lovely ladies have returned as puppets in Jonathan Rockefeller’s That Golden Girls Show!—A Puppet Parody. Capitalizing on moments from the original television show for loyal fans is where this production shines. Nostalgia quickly sets in upon entering the theater. Scenic and lighting designer David Goldstein marvelously transforms the stage into the women’s popular 1985 Miami living room and kitchen.

Aboveground Racial Politics

Underground Railroad Game, a bold and imaginative theatrical piece created by Jennifer Kidwell and Scott Sheppard, is a bawdy satire in which the audience is made to look head-on at the serious issues of race, sexuality, and how we deal with them in the aftermath of slavery. Guided by a thoughtful director, Taibi Magar, the piece exposes the damage that has been done to the national psyche by slavery’s devastating legacy, especially in terms of interracial relationships and the ways we communicate.

Two teachers—Caroline (Kidwell), an African American woman, and Stuart (Sheppard), a white man, are teaching a fifth-grade class project on the Civil War. Dressed as a Quaker abolitionist, Stuart aids a distressed runaway (Kidwell) in a campy tête-à-tête that establishes the sexual energy between the two characters immediately. Then the action abruptly changes to the bright, fluorescent-filled modern classroom where the two are enthusiastically teaching the issues of the Civil War. The teachers quickly include the “class” (i.e. the audience) in the “games” of war, incorporating “safehouse signs” and “slave dolls.” Soon the battle of the sexes is added to the mix, as well as interracial relationships, as the teachers spend time together outside the classroom.

Kidwell as Caroline gives a raw, bold, yet vulnerable interpretation of the African-American woman and her torn relationship with white men. Sheppard’s comical yet painfully exposed performance as Stuart breaks through serious barriers that society doesn’t often discuss. Sheppard and Kidwell’s dramatic exposition feels especially relevant with the racial tensions in the U.S. right now. Magar’s choices as director show the negative effects of slavery’s legacy and the way it has stunted the nation’s ability to heal through open and honest discourse.

The authors use stereotypes of African-American women from old movies such as Gone with the Wind, yet Magar has invested the piece with both melodramatic flair and honesty. Particularly riveting is a segment when Caroline is dressed in Mammy costume in daguerreotype silhouette. As Kidwell plays the runaway slave hiding in the barn, her blood-red, antebellum skirt is the focus as the character sensually moves her arms and upper body in beautiful rhythm with her song that draws Sheppard’s abolitionist to her breast. They offer a tender, painful look at the two characters’ complicated sexual relationship as a result of the shackles of enslavement. Kidwell seductively pulls her skirt up and Sheppard kneels down to her, disappearing in the velvet billows. The skirt eventually becomes a pup tent where the two teachers are discussing social issues and their relationship, foreshadowing the theme of the power of language and the bruises of misunderstanding because of white privilege.

The designers contribute sinister fog, dogs barking, creaking barn doors, crickets, and bobwhites chirping (sound design is by Mikaal Sulaiman) in the distance.

Kidwell and Sheppard have been working on this piece since they met as teachers several years ago; it is produced with the Philadelphia-based troupe Lightning Rod Special. Through the period story, they carefully expose the sexually charged, precarious relationship between African-American women and white men in this country today.

Magar guides them through some volatile moments: triggered by Stuart’s response to the phrase “nigger lover” in a classroom prank, Miss Caroline rears up in righteous indignation into a fiery S&M dance with him that is not for the prudish nor for small children. The two rage against their attraction for each other and the forces that pull them apart, leaving Teacher Stuart completely bare on stage, both physically and emotionally, and Kidwell takes Sheppard to school in an S&M dance that leaves him completely exposed, revealing a sinister essence at the core of their relationship. The play ends with both standing barren and disconnected. But with that, it is clear that only through empathy and open discussion, can we heal from our history’s wounds.

Although the past has left its ugly mark, Underground Railroad Games challenges us to look at our past with honesty and move ahead to a positive future.

Underground Railroad Game plays at Ars Nova (511 West 54th St.) through Nov. 11. Performances are at 7 p.m. Mon.-Wed. and at 8 p.m. Thurs.-Sat.; matinees are at 3 p.m. Saturdays. Tickets are $35; for more information, visit arsnovanyc.com or call (212) 352-3101.

Miranda Rights—And Wrongs

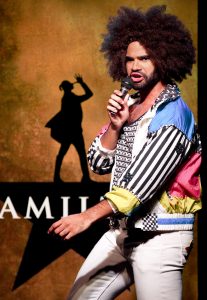

Perhaps it was inevitable that Gerard Alessandrini, the creator of many seasons of Forbidden Broadway, would be lured back by the possibilities of the phenomenon of Hamilton. Having put the long-running satirical revue on hiatus in 2014 (after Forbidden Broadway Comes Out Swinging), Alessandrini has devised a terrific new show, Spamilton, at the Triad. Structured around Lin-Manuel Miranda’s runaway hit, the show features a stronger through-line than Alessandrini usually fashions to encompass the revue elements. For lovers of musical theater, Forbidden Broadway, and Hamilton, Spamilton provides a raucous goulash of mostly on-target barbs, yet it is also in the Forbidden Broadway mold, with “appearances” by stars such as Bernadette Peters, J. Lo, Beyoncé, and, inevitably, Liza Minnelli. Most important, fans can rejoice that Alessandrini is back at the top of his game. And the targets are not just Hamilton the musical, but the art form itself, the actors in Hamilton, and anything currently on Broadway.

The revue, written and directed by Alessandrini, takes the form of a fantasia. Inspired by the Kennedys and their love of the musical, Camelot, which Jackie said she played each night at bedtime, he imagines the Obamas turning in, with the President (Chris Anthony Giles) putting on a vinyl of Hamilton. Then Alessandrini lets loose. Part biography, part parody, the show details Miranda’s upbringing, his love of musicals, and his determination to build a better Broadway musical, in a clever rap that upends the expectation of traditionalism from him:

This blue collar shining beacon/Puerto Rican/Got a lot farther/By being a lot smarter/By stretching rhymes harder/By being a trend-starter.

Lurking beneath the flattery of “trend-starter,” though, is Alessandrini’s deep skepticism about rap as a medium for shows. Later in the revue, to the tune of “Children Will Listen,” from Into the Woods, he writes:

"Careful the rap you play/No one will listen/Careful how dense the phrase/ People will leave/Or heave."

“Children like rap today/But children don’t listen/Parents may lavish praise/But they could deceive/So take it from me/Careful the rap you say/ Incessantly/No one will listen."

Yet the canny creator also realizes that Miranda didn’t come out of nowhere. He has been influenced by Sondheim, whose genius has spawned inferior work from countless lesser talents. To the music of “Another Hundred People,” from Company, Sondheim gets his share of blame:

“Another hundred syllables came out of my mouth/And fell onto the ground/While another hundred syllables are gonna go south/And are sticking around/As another hundred syllables repeat the refrain/And are waiting for us/In the second quatrain/And I’m starting to cuss/Ev’ry word I say.”

“It’s a lyric by Sondheim/All you can eat word buffet/A lyric by Sondheim/ Too hard to sing, or to play/And ev’ry day/Some say, ‘No way…’”

Nora Schell, a powerhouse singer, delivers the Sondheim parody with panache, and she plays Michelle Obama and most of the other women’s roles. Gina Kreiezmar appears as a guest diva to play a beggar woman trying to cadge tickets to Hamilton, to the tune of the Beggar Woman’s “No Place Like London” in Sweeney Todd, and as Liza Minnelli she sings, to the tune of “Down With Love,” “Down With Rap”: “Down with rap and all of the hip-hop trends/Down with rap and all of the rhymes it bends.”

Aficionados will have fun identifying the melodies and references, which include Camelot, of course, but also The Unsinkable Molly Brown, The Music Man, Sweeney Todd, Into the Woods, and non-theater music such as the theme from The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. And, thanks to Miranda’s good nature, Alessandrini has permission to use music from Hamilton itself, which he does effectively—skewering Barbra Streisand in all her narcissism and her Revolutionary garb at the Tony Awards, singing, to the music of Miranda’s big show-stopper, “I wanna be in the film when it happens, the film when it happens…”

Occasionally, Alessandrini’s swift segues may leave one confused, particularly at the appearance of an old man who missed something because he went to the bathroom. But Spamilton thrives on the energy of its cast of talented unknowns, who include Nicholas Edwards as a prancing Daveed Diggs in a volcanic wig (Diggs the actor is satirized in the number “Fresh Prince of Big Hair”) and Juwan Crawley, whose appearance in Dustin Cross’s costumes (as the genie in Aladdin and as a rather famous orphan) are the juiciest sight gags of the evening.

Whether or not you view Spamilton as a stopgap till you can score tickets to Hamilton, or as a exemplar of sharp-witted parody, Alessandrini’s show is chock-full of pleasures.

Spamilton plays through Dec. 31 at The Triad Theater. Tickets at $69 are selling quickly but are available for the popular show beginning Oct. 5. There is a two-drink minimum and cabaret seating. Performance times vary; for information and tickets, visit triadnyc.com.

Young But Wise

Shelagh Delaney was only 18 when her first play, A Taste of Honey, premiered in London in 1958 and she added to the gender diversity of the Angry Young Men of postwar British theater. The play was developed at the acclaimed producer Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop, and it contains some of Littlewood’s hallmarks, notably a jazz trio playing standards that evokes the British music hall (a popular influence in British theater, used by John Osborne as the setting for The Entertainer and by Littlewood herself in Oh, What a Lovely War!—and on through Privates on Parade, right up to One Man, Two Guv’nors in 2011).

As with Osborne, Arnold Wesker, and John Arden, the focus of the “angry theater” was the travails of the working-class English. Delaney’s play is set in Manchester, and concerns Jo, who is 17 and lives with her mother, Helen (Rachel Botchan), a sometime prostitute. For the late 1950s, and for an author of 18, A Taste of Honey is astonishingly frank and casual about taboo topics of the period. Jo refers diffidently to Helen’s “immoral earnings.” Jo herself has an affair with a black sailor (Ade Otukoya) and becomes pregnant by him. She sets up house with a fellow art student, Geoffrey (John Evans Reese), who is gay and has more nurturing instincts toward her than Helen does.

Jo’s fractious relationship with her mother is, in Delaney’s play, the fault of both characters. Rebekah Brockman’s Jo is irritatingly immature and impractical, yet self-confident, and she and Helen squabble frequently. Helen has clearly not taken a strong hand in raising her daughter, and Jo is a free spirit as a result, mouthing off in a way that the vast majority of middle-class 1950s teenagers probably wouldn’t dare to.

Meanwhile, the narcissistic Helen blows hot and cold about caring for her daughter. “Why don’t you learn from my mistakes?” she asks Jo solicitously at one point. “It takes half a life to learn from your own.” Yet she’s also capable of saying, “I never have thought about you when I’ve been happy.” It’s a measure of Delaney’s maturity that she can create characters so complex and show the struggles of their lives so vividly.

The play focuses on Jo’s coming of age. Helen has a roistering time with a former client/boyfriend named Smith (Bradford Cover, with an eyepatch), who has tracked her to their new digs. Joe resents Smith and spars with him verbally, even though he makes overtures to be kind to her. (In The Angry Theatre, John Russell Taylor, who saw Delaney’s original script, says Smith’s kindness was toned down in Littlewood’s final version.) Eventually Helen runs off with him, only returning after Smith has run off with a younger woman. Meanwhile, Jo and Geoff have established a home of a sort—Jo works in a shoe shop by day and a bar at night. But Botchan’s selfish, blundering Helen, now displaced, ousts Evans’s gentle, patient Geoff in the awkward, melancholy climax.

The play is a dream play, with flights of fancy and high theatricality in spite of its working-class milieu—Jo talks about the sailor being “an African prince,” and Geoffrey yearns to be a father figure in a heterosexual family and fit in. Characters deliver asides to the audience in the manner of Restoration comedy. Director Austin Pendleton uses the jazz trio not only to punctuate verses of songs that the characters break into, and to cover scene changes, but also as a silent chorus. When Helen shows them racy advertisements, Max Boiko (trumpet), Walter Stinson (bass), and Phil Faconti (guitar) play along and take a look with wry reactions; two of them often share the sofa with the speaking characters. (Harry Feiner’s scenic design delivers a heavier dose of realism, with its drab browns, duns and mustards, visually enlivened only by Barbara A. Bell’s bright dresses for Helen.)

Still, there’s a sense that, even with its open artifice, Delaney’s characters were lifted out of a vacuum and placed in this setting. As a dream play, it’s not as easy to adjust to or as persuasive as, say, The Glass Menagerie. Delaney never had a bigger success than A Taste of Honey, and it’s rarely revived nowadays. It has perhaps frayed a bit at the edges, but it’s still a work that continually surprises with its modern feel. The Pearl Theatre’s season opener is a welcome opportunity to see it.

The Pearl Theatre's production of A Taste of Honey will play through Oct. 30 at 555 W. 42nd St. Performances are at 7 p.m. on Sept. 20, 22, Oct. 3, 4, 10, 12, 13, 16, 20 and 24; at 8 p.m. Sept. 23, 24, Oct. 21, 22, and 29; and at 2 p.m. Oct. 2, 22, 23, and 30. Tickets are $59 and may be purchased by calling the theater at (212) 563-9261 or visiting pearltheatre.org.

That Pharmaceutical Connection

The drug that gives Ana Nogueira’s new play its name, Empathitrax, fosters complete intimacy between two people in a relationship. The users take it with water, then wait a bit and touch each other—waves of empathy ensue as the feelings of the other become utterly accessible. It’s apparent almost immediately that the man and woman in Empathitrax—Nogueira’s script identifies them only as Him and Her—need artificial stimulation. As they meet with a delivery guy from Empath in their minimalist living room to discuss dosages and procedures, they interrupt themselves, grasp at each other awkwardly, smile uncomfortably and generally broadcast that their relationship is strong but that there might be some problems.

Nogueira develops her theme carefully. Focusing on a drug that interferes with one’s natural personality traits is not a fresh topic—Placebo and The Effect have been there—but Nogueira’s play is still a strong entry in a subgenre of modern drama. It allows its actors to work with a wide range of emotions. And those actors—Jimmi Simpson and Justine Lupe as Him and Her, and Genesis Oliver, who doubles as the Empath delivery man and as Him’s buddy Matty D.—give astonishingly good performances, not just charting the emotions unleashed by the drug, but investing the science-fiction aspect of the story with credibility. As they undergo the effects of Empathitrax, they touch each other and each feels what the other is feeling. The physical empathy they enact is persuasive and overpowering.

Simpson once starred on Broadway in The Farnsworth Invention and looked set to be a fixture in the theater, but forsook it for television work. He was clearly an actor of great gifts, and they have not diminished. He uses every second of stage time, much like Vanessa Redgrave, to create a pointillist portrait. One is afraid to look away for fear of missing the tiniest apt grimace, deep breath, or shoulder shift that conveys crucial information.

If Him is calm, rational, giving and patient with his partner to a fault in their daily lives, Her can still push his buttons at times. She buys a bed they cannot afford without consulting him, and that provokes exasperation. But every interaction, every hesitation, every flash of emotion between Simpson and Lupe is precisely evoked under Adrienne Campbell-Holt’s superb direction.

Lupe’s Her is needy and insecure, and although the opening scene with the delivery man plays like a Cowardian comedy of manners, things turn darker. “This play is a comedy, until it’s not,” reads a direction in the script. And it’s quite funny for awhile, as Him subsequently meets with his buddy Matty on the rooftop to vape and describe his experience with the drug. “I guess that I didn’t know how much the little things mattered to her and she, she didn’t realize just how much I cared about her,” he says. “But now we can actually show each other, transfer the information. It’s quick and it’s potent.”

Matty tries to relate every emotion to a past drug experience: “So it’s like doing Molly?” he asks. “So like, a Xanax.” He’s an expert on artificial stimulants, but, in a scene at a party with Her, he reveals that his impetus to using drugs may well be a result of his sick father: “He’s like, almost catatonic, all the shit they have him on. It’s keeping him alive which is good, I guess. But.” To which Her responds: “But what’s the point of being alive if you aren’t really taking it all in.”

It’s a modern dilemma—the desire to experience everything. Even the rampaging use of the Internet to see life in all corners of the earth, to miss nothing, to signpost one’s existence for others to notice, is a symptom. Her tries to finesse the shortcomings of her relationship with him by adopting a dog, Rufus, who is kept in a crate and sometimes barks and sometimes is heard chewing on treats (the sound design is by Matt Otto). Rufus’s unconditional love cheers her, and Lupe has a couple monologues with the dog, in which she displays her neediness: “Do you like me even a little? Do you realize I saved your life? No one in the world knows what could have happened to you if you stayed in that shelter.”

In Nogueira’s satisfying ending, well grounded but still a surprise, the author comes down on the side of natural experience rather than chemically induced effects. Simpson’s Him does something uncharacteristic—he improvises—and the delicacy and romance of the final moments pull the play back from the darkness enveloping it. It’s no longer a comedy gone awry.

Colt Coeur's production of Empathitrax plays at HERE Arts Center (145 Sixth Ave., entrance on Dominick Street) through Oct. 1. Evening performances are at 8:30 p.m. Thursday through Saturday, and 7 p.m. Sundays and on Monday, Sept. 26. There is also a matinee at 4 p.m. on Oct. 1. Tickets are $18 and may be purchased by visiting here.org.