Samuel D. Hunter made a big splash—excuse the pun—with his play The Whale, for which he won a special Drama Desk Award in 2013. Earlier this year he was honored with a MacArthur “genius” award. His latest play is Pocatello, at Playwrights Horizons, where The Whale was mounted, and it takes place, as his plays usually do, in Idaho. But, although it starts out ambitiously, it falters midway.

Set in an Italian restaurant along the lines of Applebee’s or Old Country Kitchen, the play explores the bonds of families under stress. The opening scene sets the tone, as customers at two tables bicker and snipe. At one table is the family of the manager, Eddie (a trim, wry T.R. Knight), complaining about the lack of gluten-free pasta, among other things. At another are the wife, daughter and father of Troy (Danny Wolohan), a waiter at the restaurant. They’re the only diners during what a multicolored banner proclaims is Famiglia Week. And they’re all straight from hell.

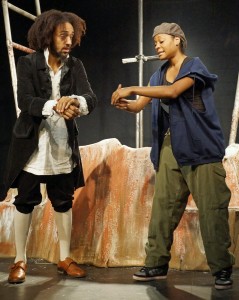

The introductions of the characters, in the midst of chaos, are carefully choreographed by director Davis McCallum with overlapping dialogue and flurries of action all over Lauren Helpern’s inviting, pitch-perfect set, replete with hanging grapes.

Meanwhile, Eddie strives to recreate the joyous meals of his childhood, but his family, already reluctant to meet, slinks away. Since Eddie is gay, at first it seems that Hunter is exploring the way that gay people must make their own families (a subtext of many Noel Coward plays, e.g. Present Laughter). After all, Eddie is also the patriarch of his "restaurant family," which, along with Troy, who used to work at a paper mill, includes Isabelle, a waitress, and Max (Cameron Scoggins), a waiter and former methamphetamine addict whom nobody else would hire. But unbeknownst to the staff, the restaurant is slated for closure, and Eddie hasn’t told them their jobs are in jeopardy.

The plot twists abound, and for a long while Hunter manages to juggle them skillfully. It is no easy thing to make decency interesting on stage, but Knight does it extremely well, usually wordlessly. He flashes a wry smile at times, or does subtle takes as other characters speak. He’s engaging and likable even as Hunter’s story starts to unravel.

The central conflict between Eddie and his family, in particular his mother, is related to his coming out. It’s simply inconceivable that a character as sensitive and intelligent as Eddie wouldn’t have traced the stress and estrangement from his mother to that event, especially since the behavior that we witness amounts to unvarnished emotional abuse. Her confession is written as a big revelation, but it feels like bogus pop psychology.

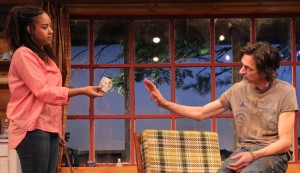

In an important scene, Eddie’s sister-in-law, Kelly (Crystal Finn), tries to explain that Nick and his mother want to run from Pocatello. “You’re trying so hard, with your family, with this place,” she tells him, but maybe you’re not gonna fix all this. Maybe it’s not worth fixing.” She echoes Nick’s exhortation: "Get out of town, make your own life.” It’s a suggestion that will probably have already occurred to the viewer, and it makes Eddie seem like a bit of a sap for not recognizing it.

The acting is generally fine. Scoggins and Jessica Dickey as Tammy enliven their addict characters with a variety of colors, and Wolohan and Hogan excel in a deeply touching exchange when Troy finds his father has escaped the assisted living home and made his way to the restaurant.

The last scene, in spite of its lack of credibility, does carry an interesting ambiguity—whether Eddie and Doris have made a pact to live in limbo, i.e., Pocatello, or whether they are at the start of a new phase of their lives. But by that time the viewer may not think it matters.

Playwrights Horizons presents Pocatello through Jan. 4. Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Monday and Tuesday; 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday; and 7:30 p.m. Sunday. Matinees are at 2:30 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. For tickets, visit playwrightshorizons.org or call Ticket Central at (212) 279-4200.