Compared with A Doll’s House and Hedda Gabler, Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts usually has gotten short shrift as a dramatic document about women’s rights, even though its protagonist, Mrs. Alving, is as modern and self-sufficient as any Ibsen heroine. Richard Eyre’s astonishing adaptation, which runs only 90 minutes without intermission at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, confirms that Ibsen’s 1882 play is as timely as ever. None of the three acts feels foreshortened—it’s a full meal. It is also a magnificent production.

Both Ibsen and George Bernard Shaw, who championed the Norwegian playwright’s work in England, kicked Victorian melodrama to the curb, as it were, and introduced politically and socially conscious realism to the stage. At BAM, Eyre makes one feel the full weight of the change.

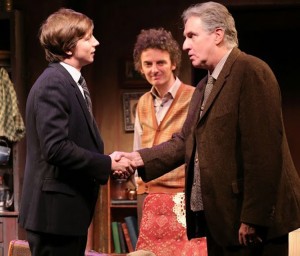

With only five characters, Ghosts also displays Ibsen’s characteristically tight plotting. Lesley Manville’s Helene Alving has welcomed her son Oswald (Billy Howle) home to Norway after has lived abroad for years. His father has died, and a new orphanage named for him is to be dedicated by Pastor Manders, a family friend, and, it turns out, someone with whom Helene had been in love. Indeed, she had left her husband, Captain Alving, with the intention of taking up with Manders, then a divinity student. Though the spark between them might easily have been fanned into a flame, he persuaded her to return to her home, where she remained as Alving’s seemingly loyal wife, though she eventually sent Oswald away to boarding school. Two additional characters, old Jacob Engstrand, a coarse and brutal carpenter with the idea of opening a “home away from home” for sailors, and his daughter, Regina, who works at the orphanage and loathes her father, are on hand as well.

As Mrs. Alving, Manville, a veteran of gritty realism in many Mike Leigh films, shows a character with personal composure and limited patience for cant. When Will Keen’s straight-laced, judgmental Manders notices pamphlets about feminism and free love on her parlor table, he takes her to task, but she challenges him—has he read them? “One must rely on the views of others,” he says, a response that echoes today in arguments involving morality and the church.

An early contretemps over whether the new orphanage should be insured provides an example of Ibsen’s mordant humor—something that director Eyre doesn’t stint on, in spite of the playwright’s reputation for seriousness. Manders understands the importance of insuring the new building, but he’s afraid that taking out insurance will imply that God can’t be trusted to protect the structure. When Helene finally acquiesces to his foolish view, Manville unveils the character’s frustration in the way she opens a desk drawer and tosses her spectacles and a blotter in. And Keen brings out every bit of Manders’s cluelessness, yet draws sympathy for a man who adheres to his hidebound principles, whose so-called morality has exposed his venality. The ghosts of the title, says Helene to Manders, are “the things that come out of the past…not just the people that haunt us, but what we inherit from our parents: dead ideas, dead customs, dead morals. They hang around us and we can’t get away from them.”

The strong stream of anticlericalism that runs through Ghosts (along with mentions of incest, syphilis, and sexual freedom) made it as big a target for condemnation as A Doll's House, and even today one can feel the earth tremble as Oswald excoriates Manders and his views. Oswald, who has lived in Paris among bohemians, espouses free love and expresses his disdain of Norwegian “worthies” who come to Paris looking for the sexual indulgences that they disapprove of at home. (One feels at times that Ibsen, who lived abroad for more than 20 years and carried on with a much younger woman, is speaking through Oswald.)

Bourgeois morality is also represented by Charlene McKenna’s Regina. She is ready for middle-class morality, and is attracted to Oswald—and vice versa. She wants the orphanage job to support herself and stay away from her father, who’s a drinker and a laborer. Old Jacob, too, schemes for advancement, but he also suspects that society would rather keep him in his place, so he latches on to Manders as an ally. One of the open questions in Eyre’s production concerns whether Manders or Engstrand is responsible for a disaster that upsets everyone’s plans.

The production, from the Almeida Theatre in London, looks terrific. Peter Mumford supplies crucial lighting, at two points a saturated red, and Tim Hatley’s set points up the compartmentalized lives of the people involved. Most important, Manville’s last scene shows that Ibsen still has the power to deliver a kick to the gut.

Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts runs through May 3 at BAM, Harvey theater. Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday, and matinees are at 3 p.m. on Sunday. Tickets may be obtained by calling 718-636-4100 or at the BAM box office at 651 Fulton St. in Brooklyn.