Jordan Harrison’s fine yet unsettling play, Marjorie Prime, is set in the future, but follows its own path. It has neither the dystopian darkness of Minority Report and dozens of other sci-fi films, nor the impulse to satire seen in Woody Allen’s classic Sleeper, and more recently, in Stephen Kaliski’s play Gluten! Rather, it takes a low-key, subtler approach to a coming world in which mankind uses artificial intelligence. It is ambitious and canny about the problems that might pose, and its 80 minutes pack a wallop.

The title character, Marjorie (Lois Smith), is 85 as the play begins. She is talking to her husband, Walter, who appears to be decades younger. But, in fact, he is Walter Prime, a designation for a computer image that is programmed with the memories and intelligence of her late husband. She has chosen the age of Walter, and the resultant computer not only absorbs information about him from her but also from others. It is, in fact, the future: the first tip-off is that Marjorie remembers visiting New York at Christmastime in her youth and seeing The Gates.

Marjorie’s daughter, Tess (Lisa Emery), and son-in-law Jon (Stephen Root), have acquired the computer to keep Marjorie company in her old age. Tess, a deeply unhappy person, is uncomfortable with the thing, and with technology in general. “Science fiction is here, Jon. Every day is science fiction,” she complains. “We buy these things that already know our moods and what we want for lunch even though we don’t know ourselves... We treat them like our loved ones.”

But Jon has persuaded her to try out the Prime. Even so, the truths that are communicated to Walter Prime may not be whole. Tess resists telling the Prime about Damian, her brother who committed suicide after bullying at school—it is left unclear for the audience whether Damian was gay or mildly autistic, but he was noticeably different, according to Tess. Marjorie has put away her memories of Damian, hiding photographs in an attic where they were discovered by Tess and Jon when Marjorie had to leave her home of 50 years.

Tess, meanwhile, struggled in the shadow of Damian, always feeling second-string, and hating her brother for taking her mother’s attention with his suicide. The family history comes out gradually, as characters die and their Primes are programmed by the survivors.

Laura Jellinek’s set suggests a future with more questionable taste in décor: she employs strongly patterned wallpaper and furnishings in pastels of turquoise, celadon, lime and teal that imbue the rooms with an antiseptic claustrophobia. (In a glaring misstep, however, she has a kitchen cupboard open outward from the bottom—impractical in any century!) Ben Stanton employs side lighting and shadows effectively. They seem to stifle as much as illuminate.

Harrison’s script relies heavily on dialogue. He carefully sows crucial tidbits early on that have a payoff for those listening closely to what the Primes eventually present as the truth. (However, the notion that Jon would feed Walter Prime data about a Christmas visit to New York City in which she saw saffron “flags” in Central Park without checking on Marjorie’s memory is not credible, since he’s so careful about gathering the facts at other times. The Gates were up for only two weeks in February 2005, not at Christmastime.)

In a particularly touching passage, Harrison comments on the quality of life in old age, as Tess complains, “There’s the half where you live and the half where you live through other people... Any new experience you have, someone is experiencing for you, to be kind. ‘Look, Mom, it’s nice outside.’”

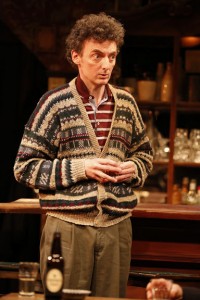

The direction by Anne Kauffman is equally skillful, as Smith, Emery, and Noah Bean’s Walter morph into Primes who are different in degree from their human models. The final scene, as three of the characters talk about the past, is both mundane and eerie. It’s clear that an approximation of humanity may be possible with the Primes, but such crucial elements of experience as truth and memory may become casualties of their technology.

Jordan Harrison's Marjorie Prime is running at Playwrights Horizons (416 West 42nd St. between 9th and 10th Aves.) in Manhattan through Jan. 24. Evening performances are at 7 p.m. on Tuesday and Wednesday, 8 p.m. on Thursday-Saturday, and 7:30 p.m. on Sunday. Matinees are at 2:30 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. Tickets are $75-$90 and can be purchased by calling 212-279-4200 or visiting TicketCentral.com.