The characters in Utility, Emily Schwend’s drably titled but fascinating new kitchen-sink drama at the Rattlestick Playwrights Theater, belong to a social milieu that seldom appears on the American stage. They’re working-class folks in the lower socioeconomic spectrum. An offer of coffee means heating a mug of water in the microwave and mixing instant powder into it. Work constitutes holding down more than one shift at a time or just picking up shifts sporadically. Dinner, often as not, is reheated leftovers.

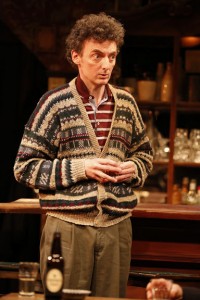

The play opens on a porch in east Texas, where Chris, a guy who has recovered from a pill addiction, is trying to wheedle Amber, his wife, into letting him move back in, just to help with the kids. Chris (James Kautz) has been sleeping on a sofa at his older brother Jim’s place, but Amber (Vanessa Vache) is reluctant to let him come back home. In this short prologue, Schwend lets us know further that Chris has cheated on Amber in the past, with someone at work; that he has a daughter, not by her, who is living with her mother; and that Amber is organized and self-sufficient and probably doesn’t need Chris’s supplementary income, even though her finances are stretched thin.

The focal point of the drama is a birthday party for Amber’s daughter, Janie. (Although the children are never seen, Kate Noll’s deft kitchen design reminds us of their presence: there are children’s drawings under magnets on the refrigerator.) Chris isn’t the child’s father—children with various parents are part of the fabric of this social stratum—but is helping to coordinate the birthday, which puts him in good stead with Amber’s mother, Laura (Melissa Hurst), who proves an unlikely champion for Chris.

“All I know,” says Laura, “is I seen Chris running around here all day long fixing up this house for a birthday party for a girl ain’t even his own daughter.” But, Amber is on top of school, doctors, and box lunches, and responds, “It’s not like it’s just suddenly easier with him here. I’m the one got two jobs, and he’s still another mouth to feed. Another person in the bathroom in the morning. And in and out of work. Can’t send a check when he says he gonna send a check… And actually? It’s easier when I don’t gotta think about him.” In these passages, Schwend displays a gift for dialogue to convey information and attitudes of her characters.

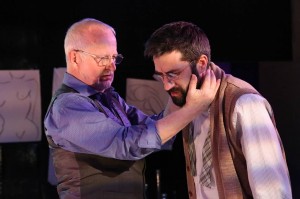

Meanwhile, Jim (Alex Grubbs) is working on restoring Amber’s house, which has apparently been damaged by flooding. He’s in and out of the building, and his presence irritates Amber even though he’s doing the work gratis. He doesn’t get much sympathy from Laura either; she has only a cold shoulder for him.

Director Jay Stull keeps tension in the action and yet lets the strands of Schwend’s drama play out, sometimes just a bit sluggishly, and at others in a pleasantly leisurely way—there’s a late scene that is daringly silent for a considerable stretch while Amber just smokes. His cast is superb. Vache is a grounded, skeptical Amber, a woman perhaps too easily irritable, but also hurt once too often by Chris. She is a formidable protagonist. Kautz finds in Chris an easygoing decency; whatever his past has been, he has left it behind, but he is also not a fully operational adult. The play’s title comes from the utility bill he has forgotten to put money down on—paying it all would be too much for this family—and the power suddenly goes off the day before the birthday party. Hurst’s Laura is also a bit of a strain for Amber; what help she offers comes with opinions, not just about Chris and Jim, but about the danger of vaccines, for instance; at the same time, she has money she has put by and is willing to lend if needed.

Finally, Grubbs as Jim gives a marvelous performance: laconic, grounded and probably in love with Amber. He finds comedy in the deadpan character, and in the comparatively brief amounts of dialogue he is given he manages to convey decency, yearning and self-restraint. The word, “utility,” carries a double meaning of electrical power and “usefulness.” In that sense, the title is apt because the work serves as a useful calling card for Schwend’s dramatic talents as well as the cast’s.

The Amoralists’ production of Utility plays through Feb. 20 at the Rattlestick Playwrights Theater (224 Waverly Place between West 11th and Perry Sts.) in Manhattan. Performances are Thursday-Saturday at 8 p.m., with a special Wednesday evening performance on Feb. 17, and a 3 p.m. matinee on Feb. 14. Tickets are $18 and may be purchased by calling 866-811-4111 or visiting https://web.ovationtix.com/trs/pr/953828.