How tightly does the average American cling to a confabulation of love? If pop culture’s steady stream of uninspired TV shows and mildly erotic paperbacks is any indication, people seem to be grasping for any and all channels that lead to answering this question. Unsurprisingly, New York theater offers an intelligent, mesmerizing counter: The Effect, a play by Lucy Prebble. The Effect has a singularly moving tension at its core: can two people fall in love under “the effect” of a powerful anti-depressant? Or is love simply the side effect of that drug?

Barrow Street Theatre’s exceptional take on this award-winning play (it received rave reviews and multiple awards in London and has struck similar chords of awe Off-Broadway), pushes us to seriously consider a fanciful four-letter word that ordinarily inks the pens of poets. Director David Cromer orchestrates this production with white-knuckled excitement at the mere prospect of discovering something unknown about love. The Effect suggests a new, intoxicating interpretation of modern romance, unbothered by moral clichés or excessive sentiment.

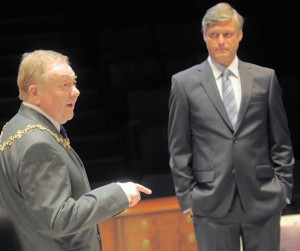

The play opens inside a sanitized hospital room, with quiet colors and sensible chairs and white lab coats. Connie Hall (played by a fantastic Susannah Flood) is being interviewed by Dr. James, her clinical supervisor. She is careful and precise, answering every question with painstaking clarity—sometimes to humorous effect. Next, Tristan Frey (a terrific Carter Hudson) plops himself down in from of Dr. James and proceeds to flirt, extemporize and generally misbehave. These two main characters could not be more different from each other. In the confines of their six-week-long aphrodisiac existence as part of the drug trial of an antidepressant, Connie and Tristan discover each other in themselves, each pushing the other to believe in their respective ideas of love.

Cromer urges nervous humor in Flood and Hudson’s performances. The two protagonists carry conversations like precocious babes endowed early with the power of speech. Flood’s Connie is a study in fastidious, think-first-talk-later practicality, but Hudson’s inspired Tristan Frey is endlessly energetic, dancer-like and hell-bent on talking Connie into falling for him. It isn’t enough to say that their chemistry is palpable; when their eyes meet, each magnetizes the other’s performance, elevating the entire production to goosepimply electricity.

As for the emotional trauma of falling in love—for it is, the play argues, a kind of trauma—Cromer reserves such hefty work for Steve Key and Kati Brazda. Understated, Brazda plays the most unexpectedly affecting character, Dr. Lorna James. As the lead psychologist of the antidepressant study, James begins her arc as a dry clinical supervisor, reining in the sexual urges of Connie and Tristan with the amused authority of an animal handler. But as her interactions with Dr. Toby Sealey (Key) reveal, she hides a deep, corrosive wound, thanks in large part to her beliefs in love and attachment. It is through James that we see the real pitfalls of love—the ones Prebble wants to warn us about.

The players are not Cromer’s only tools, however; moving walls, suggestively dark corners and flashing text are sleek supplements to the overall effect of the play (the scenic design is by Marsha Ginsberg and lighting design is by Tyler Micoleau). These additives do not distract from the entire play, as one might expect, but rather enhance Prebble’s narrative. A particularly hilarious scene involves both Connie and Tristan taking a psychological test in which they must name the colors of the words that flash on a screen before them. James dryly notes that her subjects will falter at words that they associate with emotional burden. “Father,” “diet,” “breasts” and “guilty” prove particularly difficult for our lovers.

Cromer aims to show us a precise examination of falling in love, with all its awkward pauses, fitful first moves and, yes, even sex, in all its clinical vulnerability. Prebble’s commentary on modern love is a moving, masterly ode to humanity’s endless pursuit of answers to nebulous ideas. The Effect disturbs and excites—your notions of everything from intimacy to depression will take a hit, for the better.

Barrow Street Theatre’s production of The Effect runs through Sept. 4. Evening performances are Tuesday through Sunday at 7:30 p.m.; matinees are Saturday and Sunday at 2:30 p.m. Tickets may be purchased by visiting SmartTix.com, on the phone at 212-868-4444, or in person at the Barrow Street Theatre box office, open at 1 p.m. daily. For more information, visit www.BarrowStreetTheatre.com