When actors address audiences directly, they’re said to breach the stage’s “fourth wall.” In The Mortality Machine, it’s the audience that does the breaching, penetrating all parts of the playing space and performing assigned roles side-by-side with the professionals. In this two-hour drama—site-specific, immersive, and improvisatory—part of the mystery for the playgoer is who else has bought a ticket and who’s being paid to act.

Hercules play to mix classical and original elements

Eclipses Group Theater will premiere Hercules: In Search of a Hero, a theater piece combining excerpts for Hercules and Alcestis, both by Euripides, along with original material. Using an exploratory, multidisciplinary approach, Eclipses presents Greek and non-Greek classical and modern plays in collaboration with artists of various ethnicities and cultures. Hercules contrasts the traditional male notion of heroism with a “feminine alternative.” It is conceived and directed by Ioanna Katsarou, translated by Demetri Bonaros, and has original compositions by Costas Baltazanis. The production will play from Jan. 24 to Feb. 10 at the Abrons Arts Center (466 Grand St.) as part of the @Abrons Series program. For tickets and more information, visit egtny.com.

Trick or Treat

Ghosts and demons are expected to rise up on Halloween, and the ones within the haunted house of Jack Neary’s twisted and brutal tragicomedy, Trick or Treat, do not disappoint. The walking dead linger on the staircase while the spirits of deceased relatives, as well as some long-buried secrets, emerge to effectively tear apart a family. Hints of betrayal, mental illness and physical violence pervade the air, so don’t even ask what happened in the basement. Not that Neary’s characters are wearing white sheets, bloody robes or devil horns. No, this is a far scarier and more tragic clan: a passive-aggressive, Irish-American, middle-class family in eastern Massachusetts.

Set on Halloween, the play’s first act builds to an earthquake of a revelation, while Act II is a series of aftershocks that cause sustained damage. That listing the specifics would mean unmasking all the fun is testament to the integrity of Neary’s nifty script. The past and present actions of each family member are so tightly interwoven that to mention a father’s long-ago instinctual defense of his young son is to divulge why his daughter would grow up to marry the man she did. Suffice it to say that this is a play that pits paternal protection against marital devotion, and measures the stark difference between preserving the family and preserving the family name.

Claire (Jenni Putney) offers sympathy to her father (Gordon Clapp) after a hard day in Jack Neary’s Trick or Treat. Top: Teddy (David Mason) and Johnny (Clapp) in a difficult father-son moment. Photographs by Heidi Bohnenkamp.

When we first lay eyes on Johnny Moynihan, he is seemingly alone in a large, cluttered house, preparing to receive trick-or-treaters. But, in a sensitive and engrossing performance from Gordon Clapp, something is clearly wrong. A permanent frown mars Johnny’s face, and his bulky, shuffling body seems to slowly be crushing in on itself. When his daughter, Claire (Jenni Putney), comes to call, we get a hint of Johnny’s New England accent—“Park the car,” he tells her—and an inkling of his woes. His wife, Nancy (Kathy Manfre), a victim of early onset Alzheimer’s, has reached the stage of the disease where he can no longer properly look out for her.

As Johnny describes to Claire what he has been through in dealing with Nancy over the course of the day, it might seem that the viewer has been trapped in a very depressing play about a devastating illness. But, as Johnny divulges just how he treated his dear wife in the wake of being freaked out by her behavior, it becomes clear that he is not so kindly, even though he always hands out the full-sized candy bars to the neighborhood kids, and that Neary has more on his mind than just compassionate care.

Soon Johnny’s son, Teddy (David Mason), arrives and hears of his mother’s condition. The family tensions grow palpable as we learn that Teddy is in line to become the police chief of their small town, a position once held by Johnny’s father but which Johnny never achieved. Teddy, however, has a history of violence, and Claire’s husband, an editorialist for the local paper, is out to keep him from getting the promotion. As if the tension between the three were not heated enough, nosy neighbor Hannah (Kathy McCafferty) keeps dropping by to act as a catalyst for a series of blow-ups. That she is an ex-girlfriend of Teddy’s makes matters no less volatile. By the time all the domestic matters have been sorted out, with previously undisclosed allegiances revealed and exit strategies put into place, Johnny is left virtually alone to wallow in the tragic consequences of his decisions. His world view of what it means to honor and to keep, in sickness and in health, is radically altered.

“Hints of betrayal, mental illness and physical violence pervade the air, so don’t even ask what happened in the basement.”

Clapp’s powerhouse execution of a father with all the wrong dreams receives strong support from his co-stars. Though we know a lot about Teddy before he even enters, Mason’s flying off the handle and reaching for serenity make for an explosive mix. Putney, meanwhile, supplies the right blend of compassion and disgust as the beleaguered Claire, and McCafferty makes Hannah a believable interloper, unable to stay away even as things get worse every time she drops in.

Director Carol Dunne brings a masterly pacing to the proceedings, pulling focus toward important clues while navigating the audience through a patchwork of lies. Among the clutter of scenic designer Michael Ganio’s well-worn living room are baskets of toys that may be there for Johnny’s grandkids or for a much sadder reason. Meanwhile, a jack-o’-lantern, bearing a demonic smile, looks on approvingly from atop a bookshelf.

Trick or Treat runs through Feb. 24 at 59E59 Theaters (59 E. 59th St., between Park and Madison avenues). Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. To purchase tickets, call the box office at (646) 892-7999 or visit www.59e59.org.

Bleach

Tyler Everett, the protagonist of Dan Ireland-Reeves’s compelling play Bleach, takes a utilitarian view of whoring. A recent recruit to the world’s oldest profession, Tyler (Eamon Yates) has figured out how, on any given night, to reap maximal rewards at the intersection of human sexuality’s demand and supply curves.

On Blueberry Hill

Sebastian Barry, the Irish playwright who made a theatrical splash with his 1995 play The Steward of Christendom, has since then become as renowned for his novels (The Whereabouts of Eneas McNulty, Days Without End, A Long Long Way) and only sporadically returned to the theater. On Blueberry Hill, a presentation of Origin’s 1st Irish Festival, is less a traditional play than two intertwined monologues—like The Pride of Parnell Street, a 2007 play from Barry’s hand that was presented here by the same company, Fishamble, or Brian Friel’s Faith Healer—but it is riveting.

Niall Buggy plays Christy in Sebastian Barry’s On Blueberry Hill. Top: Buggy (seated) with David Ganly as PJ, his cellmate.

Although inherently lacking the excitement of actors facing off in conflict, monologues in the right hands can be thrilling. Barry dresses his in poetic imagery that recalls the glories of J. M. Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World. Indeed, the Christian name of Synge’s hero, Christy Mahon, has been borrowed for one of the two characters, cellmates and killers. Director Jim Culleton’s production puts Barry’s gift for storytelling on full display, as the author teases out their tragic history in bits and pieces and keeps the audience guessing at why and how they became cellmates, and whether there is any connection between them.

The first speaker is PJ (David Ganly), a plump man early in middle age who is in prison (Sabine Dargent provides the minimal set, bunk beds supported by a cylindrical metal frame) for a crime that may not quite have been one. He recalls his childhood and his struggling mother in the 1960s: “We hated the English but that didn’t mean we loved ourselves,” he says, and Ganly stammers slightly as PJ; he often has downcast eyes as he describes the events that brought him to prison, but then sin weighs particularly hard on him because he was a seminarian. He is a man whose soul trembles with guilt.

While in seminary, he made friends with a younger man, Peadar, “a perfectly normal young Irish boy except he was shining with beauty. … With an accent on him that would mash spuds.” They fell in love, but on an outing to a nearby island their lives take a horrific turn in a split second that leads to PJ’s incarceration.

Meanwhile, in Christy’s monologues, we learn of his hardscrabble life. The son of a tinker who was killed in a knife fight, Christy has been the mainstay of his family since he was young. He’s daring, or perhaps foolhardy but lucky, as he takes on operating construction machinery with which he has no experience:

And the big thing on a building site is, if they ask you can you do something, you always say yes, or I always did, and one time it was ‘Can you drive a dozer?’ and I said yes, sure I had the bit of practice on a pal’s motorcycle in Ireland….

Ganly as the anguished PJ. Photographs by Patrick Redmond.

The combination of life-threatening recklessness and comic ego proves winning in Niall Buggy’s performance. He is an angry, forceful man, but in 20 years he has had no contact with his wife or children. If PJ agonizes constantly over his fatal act, Christy accepts his punishment more stoically. But he has happy memories of meeting his wife at a dance where “On Blueberry Hill” was played and of their wedding:

[H]aving the feed at the Pierre Hotel, and us all coming out into the late twilight of a summer’s night, happy as larks with the skinful of beer and burnt chicken, oh yes, and the wide bay lying there before us like the bedclothes of God.

Both Ganly and Christy conjure up the others in their lives, the richness of their freedom, both in happiness and pain. Says Christy:

Mayhem. Anger. You can do anything with anger. I mean, the bit of the gospels that I really like, when PJ is reading to me, as he does sometimes in the night-times, is the time JC goes ape-shit over the moneylenders. Some of the holy bits go over my head, but that bit I understand. I understand it perfectly.

And they conjure a third character, the guard McAllister, who puts them in a cell together as a cruel joke. He never appears, but he’s a crucial component of the story, and Barry is a master storyteller—as are the two actors and their characters. As they draw toward the end of their lives, one feels sorrow at the loss of two good men, their crimes notwithstanding. It’s well worth the visit.

The Fishamble production of On Blueberry Hill runs through Feb. 3 as part of the Origins 1st Irish Festival at 59E59 Theaters (59 E. 59th St.). Evening performances are at 7:15 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday; matinees are at 2:15 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. For tickets and information, call the box office at (646) 892-7999 from noon to 6 p.m. or visit 59e59.org.

LaBute New Theater Festival

Neil LaBute burst upon the New York theater scene 20 years ago with Bash, a trio of one-act plays. It is a form he frequently returns to, and for the fourth year in a row he is represented by an evening of three one-acts under the umbrella title, LaBute New Theater Festival. Anyone familiar with the playwright’s work knows that his plays often attempt to shock—or at the very least agitate—his audiences with provocative, you-can’t-say-that-in-public pronouncements and confessions. Seemingly ordinary and recognizable individuals give voice to amoral and dark thoughts, and a successful LaBute play prompts a fair amount of uncomfortable laughter and occasional squirming in one’s seat.

Waiting for Godot

Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot begins with a declaration of futility. Estragon, one of the play’s tramps, attempts to remove an intractable muddy boot and despairingly announces, “Nothing to be done.” This sense of existential desperation pervades the New Yiddish Rep production, performed in Yiddish with English supertitles. Director Ronit Muszkatblit’s version has to be one of the bleakest in recent memory. While the approach may not appeal to casual theatergoers, Beckett devotees will find much to savor.

Richard Saudek plays Lucky in the Yiddish translation of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. Top, from left: David Mandelbaum as Estragon and Eli Rosen as Vladimir.

Performing the play in Yiddish (Shane Baker has provided the translation) makes a great deal of sense because Godot can be viewed as a post-Holocaust response. Beckett was in the French Resistance, and he began writing the play just three years after the end of World War II. The monumental inconceivability of human cruelty, the Holocaust, and nuclear destruction pervade the text, and life, as reflected in the play, is senseless and completely expendable. As one of the characters says, people “give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.”

The production also draws on rich Yiddish performance traditions. Pre-show and intermission music includes Yiddish cabaret songs, and the pair of tramps, Vladimir and Estragon (Eli Rosen and David Mandelbaum), verbally spar with the cadence of early 20th-century Jewish comics and Borscht Belt comedians.

As the pair waits for the elusive Godot, they devise ways to pass the time. Yet unlike with other productions, Muszkatblit and her cast have not thoroughly mined the play for laughs. In the characterizations by Rosen and Mandelbaum, mustering even momentary amusement proves to be an impossible endeavor. They are simultaneously dependent upon and bored with each other. As Estragon says, “There are times when I wonder if it wouldn’t be better for us to part.” But like a couple in a codependent marriage, they bicker, hurl insults, and temporarily make up. This is their life, hour by hour, day by day, ad infinitum.

“Pre-show and intermission music includes Yiddish cabaret songs, and the pair of tramps verbally spar with the cadence of early 20th-century Jewish comics and Borscht Belt comedians.”

Their tedium is temporarily disrupted by the appearance of the arrogant landowner Pozzo (Gera Sandler) and his docile, bonded servant Lucky (Richard Saudek). Pozzo literally throws Estragon a bone, and Lucky provides a brief entertaining interlude. Even that becomes unbearable for the tramps. And when the boy (alternately played by Noam Sandler and Myron Tregubov) arrives at the end of each act to inform Estragon and Vladimir that Godot will not appear, the news is met with a collective shrug.

The effect generally works, but at times the leisurely pace and (for non-Yiddish speakers) alienating supertitles can be wearying for the audience, partly because of the central performances. Individually, Rosen and, in particular, Mandelbaum offer convincing and moving portrayals, but as a tragicomic duo, they do not always seem to be in sync. Their banter sometimes seems rather hesitant, and their physical comedy (such as lifting dead-weight bodies and trading bowler hats) can seem a bit under-rehearsed. They lack, for instance, the natural, easy timing that other clowns (Nathan Lane and Bill Irwin, to name just two) have brought to the parts. Granted, Rosen replaced another actor right before the show opened, so the pair still may be finding their rhythm.

Mandelbaum and Rosen as the tramps in Beckett’s existential tragicomedy. Photographs by Dina Raketa.

Sandler’s Pozzo is not a force of nature as one often sees, but his downplayed, almost offhand abusiveness is frightening in its ordinariness. As Lucky, Saudek is scarily good. Oppression and cruelty have sucked the life out of the character, but when ordered to dance and “think,” he is able to summon the remaining vestiges of physical and intellectual presence. Saudek’s slow-build then unstoppable first-act monologue is a coup de théâtre.

George Xenos’s tattered costumes and minimal scenery provide a dash of theatricality and creativeness: the play’s fundamental set piece, a tree—or is it, as the characters debate, a bush? Or maybe a shrub?—is the skeleton of a patio umbrella. Reza Behjat’s lighting is similarly effective, and the primary lighting effect, the moon rising, is engineered by the boy, who hangs a crumpled, illuminated globe from a visible wire.

Yiddish theater appears to be making a long-awaited New York comeback. (The acclaimed Yiddish version of Fiddler on the Roof is set to reopen Off-Broadway in a few weeks.) And while this Godot may not be the revelatory production theatergoers have been awaiting, it offers an intriguing new perspective on a familiar and well-worn play.

The New Yiddish Rep’s production of Waiting for Godot plays through Jan. 27 at the Theater at the 14th Street Y (344 East 14th St. at First Avenue). The play is performed in Yiddish with English supertitles. Evening performances are at 7:30 Monday through Sunday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are $35 and may be purchased by calling (646) 395-4310 or by visiting www.newyiddishrep.org.

Real

The simply and ironically titled Real takes place in two time periods, New York in the present day and in 1934. The shift between them calls to mind one of Alan Ayckbourn’s time-travel plays, but playwright Rodrigo Nogueira’s voice is completely different. In the opening scene, a woman named Dominique (Rebecca Gibel), a retired concert performer, is hosting a dinner party with her husband (Charlie Pollock), who has revealed to the couple who have joined them that Dominique is practicing again.

The guests, Dominique’s best friend (Gabriela Garcia) and her husband, a professor (Keith Reddin plays the Polonius-like character, knowledgeable but loquacious, with an emphasis on irritating blather rather than comedy), are astonished. But it’s symptomatic of Nogueira’s obliqueness that one never learns just what instrument it is that Dominique plays, although composer Quentin Chiappetta has provided lovely music for a chamber trio (violin, viola, cello) that is integral to the plot and that one hears periodically and at length. The central conceit of the play is that the fugal form of the music introduces a main theme and then another joins it, and, by the end, the second theme has become the primary one, and the initial theme is subordinate; it connects easily to the work on display.

Darwin Del Fabro plays Dominic, a struggling composer in 1934, in Rodrigo Nogueira’s Real. Top, from left: Gabriela Garcia, Rebecca Gibel and Keith Reddin.

Dominique has become obsessed with a play she’s reading, and it’s actually a passage about that play, and its historical basis, that provides the most startling moment in Nogueira’s 70-minute drama.

Dominique: It’s about a young artist. An immigrant, actually, who lived here in the 1930’s, during the Mexican Repatriation.

Best friend’s husband: “Mexican Repatriation”?

Dominique: I didn’t know about this either. It was part of the plan to save the country from the Depression: mass deportations based on whether or not a person looked Mexican. … One million people were forced to leave. Most of them birthright citizens.

Best friend’s husband: How come I never heard of that?

Dominique: Because we tend rewrite history to create good memories that never existed.

At the end of the first scene, Dominique, with a bend and a heave of her chest, as if she’s having a heart attack or about to cough up an alien, becomes this young male artist, who is a composer named Dominic (Darwin Del Fabro), living in 1934. Thereafter the scenes alternate between Dominique and Dominic, marked out by music.

The actors in the modern segment portray ones in the earlier era as well, but the only characters to whom Nogueira has assigned names are Dominic and Dominique. Perhaps it’s his intention to show that the artist stands isolated from others no matter when he or she lives. Both Dominique and Dominic struggle with family obligations that hinder or interrupt their work, but there’s also a good deal of the story that is frustratingly uncertain. The chief allies in Dominic’s life are a maid (Garcia), who is a friend, and a second professor, who is a mentor (Reddin again). It is this professor who may provide a clue to Nogueira’s point: “Something is always happening to us. What is life but an interminable series of happenings? Or better, one never-ending happening.”

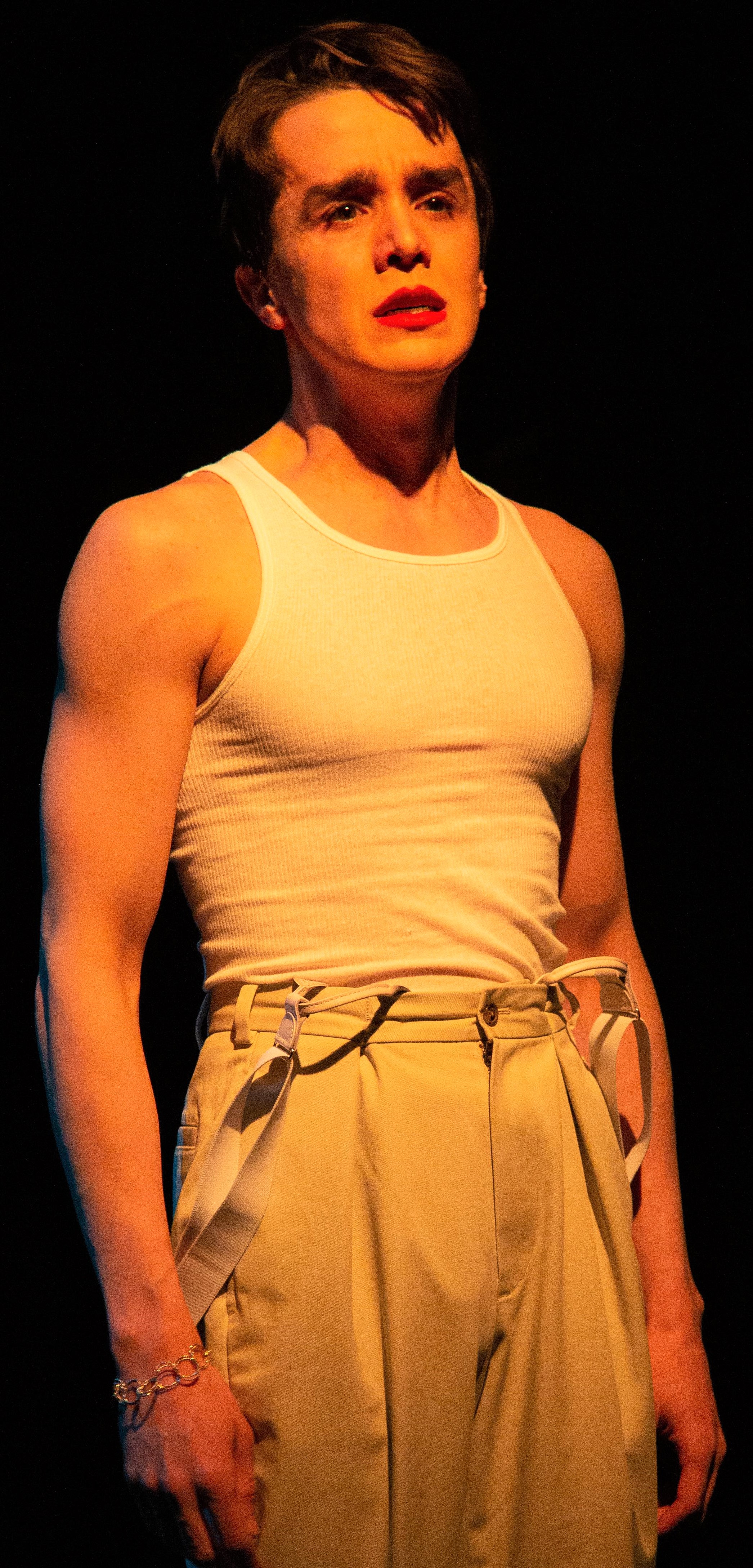

The key adversary in Dominic’s life is his overbearing father, and, under Erin Ortman’s direction, the brutishness that Pollock conveys as the father is more overt than that of the husband, whose flashes of temper are enough for the brawny actor to indicate a bully. Dominic’s father wants his son to abandon composing and return to his control. He knows Dominic is gay—he finds him with lipstick on—and he means to stamp it out. There is a subtext here, too, of society’s mistreatment of both homosexuals and women as inferior beings whose struggle to become mainstream artists poses greater hurdles than heterosexuals face.

Reddin as a dinner guest (left) speaks with his host, Dominique’s husband (Charlie Pollock). Photographs by Miguel de Oliveira.

Gibel as Dominique has the trickiest part, since she seems at times to be oblivious to her surroundings, and she is often a cipher. She has scant maternal pride in her child, and her transformation into Dominic raises questions that Nogueira leaves up to interpretation. Is Dominic dreaming of the future—he seems to know of Dominique’s existence—or is each channeling the other’s personality, forward and backward in time? Is one story real and one imagined? Are both real? Or is the story, as the professor has noted, one “never-ending happening”?

If one does not come away with an answer, Real at least shows Nogueira’s gift for poetic lyricism, and the questions he raises linger. It’s not a straightforward piece of theater, but it’s often fascinating, and it’s refreshing to find a theatrical voice as iconoclastic as Nogueira’s.

The Tank’s production of Real runs through Jan. 20 at 312 W. 36th St., 1st Floor. Evening performances are at 8 p.m. Thursday through Saturday; matinees are at 4 p.m. Friday through Sunday. For tickets and information, call (212) 563-6269 or visit thetanknyc.org.

Blue Ridge

Last year, in one of the most exciting Off-Broadway debuts of the season, the Ensemble Studio Theatre staged Abby Rosebrock’s Dido of Idaho, a darkly comic manifesto on feminism in the face of infidelity, and morals in the face of family dysfunction. Rosebrock has now returned with another new work, a character-driven drama called Blue Ridge, presented by the Atlantic Theater Company.

As with Dido, a cheating man and the effect he has on the friendship between two women is at the center of the play’s emancipatory storyline, and both works share an affinity for Tennessee Williams references as well as a certain skepticism when it comes to southern U.S. Christianity. Even if Blue Ridge is lacking the razor-sharp wit and stunning surprises of Dido, Rosebrock nonetheless succeeds in creating six well-rounded characters with believable flaws and inescapable fates. There are few explosions to be found here, but the simmering tensions brought to bear by a strong ensemble of actors under the tight direction of Taibi Magar provide a satisfying status quo; they are a happy indication of the playwright’s continuing growth.

Chris Stack, as Hern, and Kristolyn Lloyd, as Cherie, share an intimate moment in Abby Rosebrock’s Blue Ridge. Top: Alison (Marin Ireland) and Cole (Peter Mark Kendale) work on their issues.

Set primarily in the living room of a Christian halfway house in North Carolina, Blue Ridge opens on Bible Study Wednesday. The home’s newest resident, Alison (Marin Ireland), is struggling to fit in. Fidgety and more familiar with the writings of Carrie Underwood than those of the Apostles, her manic way with words brings an uncomfortable energy to the group. It is also an outward sign of her anger issues. A high school English teacher who took an ax to her principal’s car after an emotional entanglement, Alison is in a constant state of flux between being humorously energetic and dangerous to herself and those around her.

As the story progresses from November to Christmas Day, Alison and her “intermittent explosive disorder” build and destroy relationships with her overseers as well as with her “inmate” colleagues. These include Cherie (Kristolyn Lloyd), a fellow teacher who is there voluntarily to work through her addiction issues; Wade (Kyle Beltran), a guitar-strumming voice of reason making his way through the 12-step program; Cole (Peter Mark Kendale), a deep-thinking Army vet whose previous residence was a psychiatric institute; Pastor Hern (Chris Stack), their religious leader with intimacy issues of his own; and Grace (Nicole Lewis), the optimistic and overstretched manager of the home.

Wade (Kyle Beltran), plays for Cherie (Lloyd). Photographs by Ahron R. Foster.

With this boisterous performance, Ireland seals her position as Off-Broadway’s foremost portrayer of put-upon, lower-middle-class Caucasian women. From her slaughterhouse job in Kill Floor (2015, Lincoln Center Theatre) to her role as a Polish immigrant housekeeper in Ironbound (2016, Rattlestick Theater) to her excellent interpretation of a traumatized professor and single mother in On the Exhale (2017, Roundabout Underground), men have tried to break her characters in nearly every way imaginable. This time, damaged already from her relationship with her boss, Alison is triggered by Pastor Hern and his proclivities. The collateral damage includes the end of her friendship with Cherie, emotional tumult with Wade and physical aggression with Cole. Rosebrock’s neat trick here is that none of these characters is actually villainous. Each moves forward with only the best intentions, but they are ultimately undone by their mental, emotional and spiritual frailties. Kendale brings a riveting stoic minimalism mixed with an odd playfulness to Cole. Beltran’s outward calm betrays just enough of Wade’s internal struggles. And Lloyd’s Cherie, trusting and then betrayed, is rendered at just the right temperature. She also provides the ultimate dialect-infused observation in the work’s examination of sex and consent:

Not only does no always mean no, but.

Sometimes yes means juss means, I'm only doin this cause I fill like you'll leave me er cheat on me if I don't--

Cause iss not safe out there, y'all's hillbilly asses runnin around, I don't wanna be single again, / so--

I guess I consent to this act, but.

S'not cause yer special.

Scenic designer Adam Rigg’s spacious living area, set in front of a row of towering Carolina pine trees, seems too pristine and stain-free for a sanctuary that sees so much physical and emotional traffic, although, as Alison points out, “the Yelp review said best in Southern Appalachia.” The production’s final scene takes place in a high school, but Rigg offers no effort here beyond pushing the furniture to the side and throwing some plastic chairs into the middle of the room. Perhaps that’s what a New York playwright gets for adding a completely new locale in the last seven pages of the script, but the audience shouldn’t have to suffer the results.

Blue Ridge plays through Jan. 26 at the Atlantic Theater, 336 W. 20th St. Performances are at 7 p.m. on Sunday and Tuesday, and 8 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. For more information and to purchase tickets, call (866) 811-4111 or visit atlantictheater.org/blue-ridge.

I’m Not A Comedian, I’m Lenny Bruce

“Obscene, provocative, criminal, controversial”—those are words used to describe Lenny Bruce, the stand-up comedian and scathing social critic who gained popularity in the 1950s and ’60s. I’m Not A Comedian, I’m Lenny Bruce, written by and starring Ronnie Marmo, captures both the acerbic and the soft sides of Bruce, who was a man seeking a voice in an oppressive time for free speech.

Noura

Heather Raffo’s Noura scrutinizes the issue of assimilation of refugees into American society by looking at the experience of the title character, an Iraqi woman. Noura (played by Raffo herself) is a stern but loving mother and wife who escaped the ISIS capture of Mosul with her husband, Tareq (Nabil Elouahabi). After setting down roots in the new country, Noura finds that she desperately misses her hometown traditions. Raffo’s play echoes a question that Arthur Miller, in his essay The Family in the Modern Drama, asks: “How may a man make of an outside world a home?” For Raffo, the question is: “What keeps a family together?” The play reveals ways that American life can create isolation more than togetherness.

Liam Campora (left) plays Yazen, or Alex, and Matthew David is Rafa’a, a family friend, in Heather Raffo’s Noura. Top: Raffo as Noura, with Nabil Elouahabi as her husband, Tareq.

Noura, one of the Christian minority in Mosul, holds on to the Christmas traditions she was raised with as the only things left from the rubble of her hometown. She remembers the way her old neighbors would visit her father’s house on Christmas for a jubilee of dancing, good food and conversation. But in America the fast-paced and alienating effects of social media and personal technologies, such as cell phones and gaming systems, have made it harder for her family to hold on to those traditions.

Her son, whom she calls Yazen but who is also known by an Americanized name, Alex (Liam Campora), is just interested in his PlayStation and hates the fast his family observes. He begs to live a normal American life. Tareq, meanwhile, has come to terms with his new life. He is no longer able to be a surgeon as he once was in Mosul; he now works at a sandwich shop and takes up shifts that cut into his spending time with the family. Noura is thinking of continuing her career as an architect and struggles with how small and uncommunal her family has become. Noura, directed by Joanna Settle, shows that retaining one’s true identity in a new country is a struggle filled with compromises.

There’s also the family’s close friend, Rafa’a (Matthew David) and Maryam (Dahlia Azama), an orphan from Mosul who is sponsored by Noura and Tareq. Rafa’a serves as an interesting sounding board to Noura’s concerns about the life in Mosul, as well as Tareq’s sacrificing of his career and whether or not they have made the right choices in the years they have lived in America. Maryam, who comes for the holidays before going back to Stanford, carries a secret that causes Noura to question holding on to the traditions. She feels pressure to reveal the secrets she carried overseas to New York. The shorthand question in Raffo’s play is summed up by one that Rafa’a asks: Is holding on the old ways necessary?

Raffo and Elouahabi with Dahlia Azama (left) as Maryam. Photographs by Joan Marcus.

The set, designed by Andrew Lieberman, is grounded by a Christmas tree. Lighting designer Masha Tiriming’s lights gently swirl around the tree and glisten like stars in the darkness. It is a constant reminder of the holiday spirit: a time of togetherness and cheer, but it all looms over Noura’s family, who have splintered off from the traditions of her youth in Mosul. In the middle area is a tall structure that looks like a curved cage that encapsulates the family’s coming-together space; books, teapot, and other ornaments lie on the shelf attached to the structure. The table serves as a dinner table and a work station for Noura and is always cluttered. The floor and wall in Lieberman’s set are tiled with an Aramaic design that evokes the idea of the life that was left behind and the life that they are forced to embraced within their home.

But they also recognize the drawbacks of their old life. The communal life that Noura yearns for is mostly out of the sadness of the past she has left behind. Mosul also has a rugged individualism where there are Christian communities and Muslim communities that have strict rules of when mingling amongst each other. Middle Eastern culture prides itself on “deeply interwoven social fabric of community,” Raffo states in the program, while American culture “prides itself on rugged individualism.”

The actors embody the conflicts with intensity, their characters all fighting to have their perspectives heard. “What’s wrong with feeling safe?” says Tareq. “I’m grateful that there is a place we can reinvent ourselves, a place we can forget.” Noura responds, “I don’t want to forget! I’m trying desperately to remember who the hell I am.” There aren’t any clear answers in how to live their lives as true Iraqi-Americans, and no one gains leverage over another’s opinion.

What Noura does successfully is explore the challenges of living free and happy as an immigrant in America from many angles, as the characters express the various ways identity and culture can fulfill one’s sense of being—but it also shows how malleable traditions may become in the need for survival.

Slave Play

Jeremy O. Harris makes an impressive splash with Slave Play, a fascinating, often hilarious, sometimes bumpy, and ultimately serious look at sex and power in modern interracial relationships. The New York Theatre Workshop production also whets one’s appetite for Daddy, a second play of Harris’s that will be seen in the spring at the Vineyard Theatre.

The Net Will Appear

Bernard and Rory, the only characters in Erin Mallon’s The Net Will Appear, are next-door neighbors in Toledo, Ohio. Bernard is a curmudgeonly 75-year-old with a penchant for bird-watching. Rory, age 9, is a wiseacre whose chatter is laced with malapropisms and bawdy phrases she doesn’t understand fully.

Eve Johnson as Rory in Erin Mallon’s The Net Will Appear at 59E59 Theaters. Top: Richard Masur as Bernard. Photographs by Jody Christopherson.

The play opens with the characters’ first encounter—contentious and funny, with a promise of dramatic fireworks to follow. The two are on adjacent roofs, seeking sanctuary from family life. Bernard (Richard Masur) craves solitude; Rory (Eve Johnson), who’s never inclined to silence, tries repeatedly to engage Bernard with her juvenile brand of badinage.

Bernard is an Episcopalian with a drinking problem. He’s polite, though sometimes impatient; and he keeps his own counsel. Rory is a Jewish student at a Roman Catholic grade school. Her conversation is unfiltered. “Everyone thinks you’re a psycho,” she informs Bernard. The odds appear slim that these dissimilar souls can find common ground. In situation comedies of this ilk, though, strange bedfellows inevitably end up best friends.

Before the first scene is over, it’s evident that under its veneer of comic palaver, The Net Will Appear is a melancholy study of youth and age. “I don’t have much past and you don’t have much future,” Rory informs Bernard with a child’s unwitting cruelty. As the action progresses through the seasons of a year, Mallon introduces themes of social importance—most notably, the kinds of anguish suffered nowadays by the youngest and the oldest in American society.

Rory—a child of divorce who seldom sees her father—feels uncertain and out of place in the household her mother has established with a new husband. Rory’s mother is suffering from postpartum depression; the stepfather is egotistical; and a new half-sister is usurping all the affection the family can muster.

Bernard is principal caregiver for his wife, Irma (one of the play’s several offstage characters). Irma’s personality is being leached away by dementia; and Bernard grieves for the loss of his adored companion while attending to the remnant of her that hasn’t been extinguished by Alzheimer’s disease.

Mallon’s script is efficiently constructed and poignant, but there’s little verisimilitude here. The dramatic situation is contrived; the characters are fabricated rather than observed; and the dialogue rises only intermittently above the glossy superficiality of 1980s television comedy. According to formula, the play’s strange bedfellows come to appreciate, even love, each other. Rory’s innocence awakens Bernard’s paternal instincts and, under his tutelage, she becomes sensitive to the wonders around them. “First robin sighting of the season,” he says. “Look at that beautiful red breast.” (Rory, who thinks “breast” is a dirty word, is mightily titillated by that remark.)

Masur in the monologue that is the emotional high point of The Net Will Appear.

While Rory’s guilelessness ultimately endears her to Bernard, the play’s spectators are likely to respond with varying degrees of tolerance for the cute-as-pie dialogue Mallon has concocted for the little girl. The topical references that punctuate Rory’s comic patter are particularly irksome. Take, for instance, the wacky names she gives her possessions: a favorite doll is called Netflix, her cat is Dr. Phil, and the bathtub is “Harriet Tubman.” Like so much else in The Net Will Appear, these jokes, with their transitory shelf life, are disposable.

What’s most satisfying about this production is Masur’s distinguished performance. Renowned for character roles on Broadway, in movies, and on television, Masur makes Bernard’s grief-stricken monologue about his wife’s vanishing personality the most authentic and memorable sequence of the play. Undeterred by W.C. Fields’ warning that actors should “never work with children or animals,” Masur gives a touching performance, enhanced by evident empathy with his younger co-star but never upstaged by her undeniable (for want of a better word) cuteness.

The Net Will Appear takes place entirely on the rooftops of the two houses. Scenic designer Matthew J. Fick has supplied a realistic, eye-appealing set, with the roofs separated by a space at center stage that’s supposed to be too wide for either character to jump across safely. Each actor is confined to his or her roof throughout the 80 minutes of the performance. That spatial separation is a tough assignment for players who’re supposed to depict affection that escalates scene by scene. Mark Cirnigliaro’s capable direction minimizes the awkwardness of all that distance, but direction can’t transform counterfeit dialogue into dramatic gold. What saves the day is Masur’s virtuosity, which redeems a predictable comedy-drama and makes the joyous final scene soar like one of Bernard’s beloved songbirds.

The Net Will Appear runs through Dec. 30 at 59E59 Theaters (59 E. 59th St., between Park and Madison). Evening performances are at 7:15 p.m. Tuesdays to Saturdays; matinees are at 2:15 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays. For information and tickets, call (646) 892-7999 or visit 59e59.org.

The Hard Problem

Fans of Tom Stoppard who are used to the fizzy humor of Travesties, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, or Arcadia should be cautioned that The Hard Problem finds him in his other mode, tackling serious issues with less levity, as he did in The Coast of Utopia and The Real Thing. This time around the paramount concern is the title phrase used by scientists: how does consciousness come about? Connected to it are notions of altruism vs. egoism, with doses of coincidence, conscience, evolution, divinity, business ethics and other meaty subjects thrown in. And yet there are still moments of humor in Jack O’Brien’s fascinating production of this twisty play—a brainiac’s sumptuous meal laid out for the layman.

The playwright begins with an amusing bit of misdirection, as a man and woman debate what appears to be her plea in a case of jewel theft that she is involved in. Soon, though, it’s apparent that they’re engaging in game theory, specifically, the Prisoner’s Dilemma. The woman, Hilary (Adelaide Clemens), is trying to decide the best way to proceed. Her companion, Spike (Chris O’Shea), is her tutor, and he is trying to instill in her the necessity of admitting nothing, a survival strategy that will be familiar to anyone who has watched a police show on TV. “Two rational prisoners will betray each other even though they know they would have done better to trust each other,” he explains. The exercise is to prepare Hilary for a job interview at the Krohl Institute, which studies brain science.

Karoline Xu (left) is Bo and Adelaide Clemens is Hilary in Tom Stoppard’s The Hard Problem. Top: Clemens with Chris O’Shea as Spike.

In Hilary, Stoppard has, unusually for him, written a fascinating female character who carries the story. Clemens invests her with anguish, politeness, uncertainty and decency—all of which run counter to Spike’s hard-nosed ruthlessness. O’Shea’s Spike is also a casual sexual liaison for Hilary, and O’Shea offsets his good looks by imbuing the transactional Spike with a genteel chill.

Hilary gets the job at Krohl while her principal rival, Amal (Eshan Bajpay), is rejected. But after Amal draws the attention of Krohl himself (Jon Tenney, who alternates ruthless telephone conversations with moments of near-tenderness with his teenage daughter Cathy), he gets a job on the business side of the company. In exploring how the brain works, the Krohl Institute scientists hope to explain the nature of consciousness; however, Krohl, a billionaire hedge-fund manager, is only interested in ways the science can help him corner or disrupt business markets.

Hilary’s reluctance to embrace the mercenary tenets that Krohl, Spike, and Amal follow is due to her having given up a child for adoption when she was a teenager; the emotional trauma of her actions leads her to prayer and belief in a supreme being. The atheistic Spike, however, finds prayer a useless indulgence. A likable devil’s advocate, he moves out of her orbit, only to return later on. But while he’s there, the debate is lively:

Spike: It’s pathetic to rely on a supreme being to underwrite what you call your values. Why are you afraid of making your own?

Hilary: You don’t claim to make your own. What’s the difference between a supreme being and being programmed by your biology?

Spike: Freedom. I can override the programming.

Other characters come into play: Julia (Nina Grollman), an old school friend of Hilary’s, and her partner Ursula (Tara Summers), who works at Krohl and gives Hilary advice to get her through that first interview. And Leo (Robert Petkoff), who hires her and mentors her. Most important is perhaps Bo (Karoline Xu), who becomes Hilary’s assistant and has a theory of her own that she wants to pursue with Hilary’s backing.

Jon Tenney plays a billionaire hedge fund manager and Katie Beth Hall is his adopted daughter in The Hard Problem. Photographs by Paul Kolnik.

In Stoppard’s hands, the characters’ motives are always clear even when the intellectual demands on the audience are at their fiercest.

Hilary: I haven’t written anything which isn’t in plain sight. What is to be done with the sublime if you’re proud to be a materialist? To save the appearance of value, no theory is too unlikely, no idea too far-out to float so long as it sounds like science … elementary particles with teeny-weeny consciousness; or a cosmos with attitude; or the life of the mind as the software of a biological computer. These are desperate measures, Spike!

But after Hilary, in an altruistic move, supports a theory of Bo’s for which Bo, a math whiz, has provided statistics, things take an unexpected turn, and Hilary’s roller-coaster ride at Krohl comes to an end, albeit with a delicate emotional coda. As a playwright of ideas, Stoppard has no peer, and The Hard Problem, while it requires listening closely, is not hard to watch.

Tom Stoppard’s The Hard Problem plays through Jan. 6 at Lincoln Center’s Mitzi Newhouse Theater (150 W. 65th St.). Evening performances are at 8 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Wednesday and Saturday and at 3 p.m. Sunday. For tickets and information, call Telecharge at (212) 239-6200 or visit lct.org.

Selkie

A relationship goes crashing into the shores of money, love and drugs during a beach vacation in Krista Knight’s often confusing Selkie, named after a mischievous mythical creature in Scottish folklore. A selkie, also known as a water fairy can transform into beautiful woman with the removal of her magical cloak. Knight’s play, though, is set in a warmer climate. It begins with a married couple, Deanna (Toni Ann DeNoble) and Keaton (Federico Rodriguez), making their way to their hotel room in a foreign country. They’re giddy with excitement and ready to tackle this vacation as if they are on spring break, but they’re actually Americans on an extended trip, for reasons never clarified.

Quicksand

Quicksand is an apt name for the ambitious world premiere production of Regina Robbins’ theatrical adaptation of Nella Larsen’s semi-autobiographical work of fiction, written in 1928 and set in the same period. It chronicles the story of Helga Crane, a woman of both mixed ancestry and mixed race, who is, for that very reason, a tortured soul.

Born to a black, West Indian father who disappeared soon after her birth, and a white, Danish mother who raised her in the U.S. and in Denmark, the fair-skinned and exotic-looking Helga (Gabrielle Laurendine) cannot escape her bilingual, bicultural and biracial status. Her mother died when she was 15; her mother’s brother sent her away to school, where she received a good education; and she became a teacher at an all-black college. The conflict between her white and black selves produced a complex psychological character. Helga carries around a lot of heavy baggage, literally and figuratively, and her pain is palpable.

Gabrielle Laurendine, playing the exotic and enigmatic Helga Crane, poses for famous Danish painter Axel Olsen (Michael Quattrone) in Quicksand. Top: Laurendine’s Helga surrounded by the Ensemble. Photographs by Anais Koivisto.

The play begins in Tennessee, where she announces that she is quitting her teaching job, because she is “frustrated,” “tired” and “disgusted” by the “hypocrisy” and “cruelty” that pervade the all-black college, Naxos. Here, Laurendine’s Helga makes the first of many on-stage costume changes (the costumes are by Asia-Anansi McCallum). She also packs a hefty leather suitcase and boards the train to Chicago, hoping her uncle, Peter Nilssen, will be there for her. Her optimism is quashed by her uncle’s new wife, who is appalled by the mixed-race Helga’s claim to be family, and who assures her, “I am not your aunt, and my husband is not your uncle. Do not come back here.” The church provides Helga with no solace either, and she dismisses religion as “hollow” and “phony,” saying, “No one here cares about me.”

With no hope of permanent work and no one to keep her in Chicago, Helga gets a temporary position assisting a Harlem-based socialite, Mrs. Hayes-Rore (Veronique Jeanmarie) and finds her way to New York City. She is encouraged by the warm welcome she receives in Harlem, and is stimulated by the cultural and social renaissance of the 1920s under way there, but it’s not long before she becomes restless and dissatisfied. A letter from her uncle in Chicago, terminating his relationship with her, advises her to go to Denmark; he encloses a check for $5,000 which helps her decision to move on again.

Denmark offers Helga a reception that is entirely different. Her Danish aunt and uncle embrace her; they provide her with a loving home and access to a bourgeois lifestyle; they introduce her to several eligible men, one of whom proposes to her, but she refuses to enter into a mixed marriage. Heading back to New York again, Helga struggles to find a place where she can feel at home.

“The conflict between her white and black selves produced a complex psychological character. Helga carries around a lot of heavy baggage, literally and figuratively, and her pain is palpable.”

Interesting though Helga’s story may be, Anais Koivisto’s production is too long. It’s laden with layers of exposition, (including flashbacks, which are not incongruous but which can be a distraction; they ultimately confuse the flow, until the relevance becomes clear a beat or so afterward). It feels as if every single page of the novel is being acted out, with some repetition for emphasis, resulting in a sinking, never-ending feeling.

It is also weighed down by a large number of historical, social, cultural, and literary references. There are appearances by Booker T. Washington, Paul Robeson, and Al Jolson, to name a few. Many of them are lost amid the sheer volume of information the audience is asked to consume. A story of such epic proportions might work better if it were broken up into parts—there is enough material here for a trilogy.

On the other hand, the show is lifted and well-supported by charming interludes such as the train journey; the walk through Chicago, and the soup of the day, which are cleverly achieved by Allison Beler’s choreography, Tekla Monson’s simple, moveable set, and a versatile 11-actor ensemble that also serves as a chorus. Special credit goes to Laurendine, along with Malloree Hill, who plays Aunt Katrina, and Chris Wight as Uncle Paul for performing the opening scene of Act II in Danish, and managing to get their message across!

Quicksand is at the IRT Theater (154 Christopher St., between Washington and Greenwich streets) through Dec. 15. Performances are at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday, with added performances at 3 p.m. Dec. 7; 7:30 p.m. on Dec. 9; and at 4 and 8 p.m. on Dec. 11. For tickets and more information, call Brown Paper Tickets at (800) 838-3006 or visit www.everydayinferno.com.

The Tricky Part

Almost 15 years have passed since Martin Moran’s The Tricky Part premiered Off-Broadway. In 2004, stories of authority figures preying on children, though in the news, were not the media commonplace they’ve become. This solo drama about the author’s sexual relationship with an adult counselor from a Roman Catholic boys’ camp was an eye-opening tale of childhood trauma and its myriad aftereffects. Back then Moran’s accomplished performance of his own material, mixing pain and humor, registered as valiant self-exposure, affording audiences unprecedented insights about a stigmatized subject.

Martin Moran displays a photograph of himself at age 12 that was taken by camp counselor Bob. Top: Moran addresses the audience in the Barrow Group revival of The Tricky Part.

Over the past decade and a half, society has become increasingly conscious of predatory sexual behavior. It’s now accepted that this gruesome social phenomenon has always been more prevalent than acknowledged. The topic permeates media discourse, so it’s no wonder that the Barrow Group, the theater company with which Moran developed this play, is reviving it. But is it possible, after all that has been learned, for The Tricky Part to retain the supercharged impact it had in those less wised-up days when it premiered?

Honored with a special citation from the Obie committee and two Drama Desk nominations in the 2003–04 season, The Tricky Part chronicles Moran’s growing up middle-middle class and Catholic in suburban Denver. The academically gifted Marty (as he was called then) was the kind of charismatic kid who regularly lands leading roles in school plays. Seeing the onstage photograph of the 12-year-old, the audience can’t miss how filled with promise this lad must have been in 1972 when counselor Bob—30-ish, likable, and a consummate manipulator—asserted himself as mentor and seducer. (The photograph of Marty, visible onstage throughout the performance, was taken by Bob at the start of their relationship.)

On an overnight camping trip, Bob—rumored to have been a seminarian—fondles the vulnerable Marty. Drawing the boy into his sleeping bag, Bob initiates three years of sexual dominance that are followed by years of residual influence. The barely pubescent Marty knows nothing of sex beyond an elliptical account in the Boy Scout handbook. He’s conscious of being attracted to men (a fact Bob must have sensed), and he’s simultaneously aroused and repelled by Bob’s adult body and his caresses.

The bond that develops between man and boy becomes an obsession for Marty, upsetting his emotional balance with a blend of guilt, shame, and fear. Tormented by suicidal thoughts throughout high school, Marty has close calls with pills and his father’s .22. In due course, his anxious, depressed adolescence is replaced by a depressed adulthood that’s haunted with recollections of Bob’s misconduct and marked by compulsive sexual behavior.

Moran at an exuberant moment in his autobiographical monodrama. Photographs by Edward T. Morris.

Seth Barrish, who directed the original, does the same for this production, showing the delicacy of a conductor interpreting a complex symphony transcribed for a single instrument. In the course of 90 minutes, Moran’s performance varies widely in tempi and dynamics, yet the momentum never lags.

Elizabeth Mak’s lighting, effective throughout, is crucial to the dramatic power of the sequence depicting Bob’s first sexual overture and Marty’s capitulation. This long, central scene would be raw and discomfiting under any circumstances, but Mak, by decreasing illumination gradually until nothing is visible except the actor’s face, lends it an unnerving sense of intimacy.

At 58, Moran still has sufficient boyish charm to be credible as he travels backward in time. His beautifully written script steers clear of self-pity, pop psychology, and agitprop, and dramatizes with exquisite simplicity a complex individual’s response to adversity. Since the original Off-Broadway engagement, Moran has performed this drama for runs of various lengths in London, San Francisco, Seattle, San Jose, Denver, Canada, India, and Poland. Yet his emotional interpretation of the script and all its characters is vivid, believable, and unremittingly forceful, as though he’s living these experiences for the first time.

What’s “trickiest” about Moran’s saga is that his relationship with Bob, both historically and even after the confrontation that provides the play’s climax, has positive as well as sinister aspects. “I want to disown it,” says the grown-up Martin, “but it flashes through me that with this guy I rafted a river, watched a calf being born, cleared a field, conquered a glacier, learned a heifer from a Holstein, a spruce from a cedar.” Bob did damage, yet Moran wouldn’t be the strong figure he is today, nor would his play have its distinctive moral voice, without the totality of his experiences.

The Tricky Part runs through Dec. 16 at The Barrow Group (312 W. 36th St.). Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. Thursday to Monday; matinees are at 3 p.m. Dec. 8 and 16. For information and tickets, call (866) 811-4111 or visit barrowgroup.org.

Wild Goose Dreams

The Internet and technology allow us to be connected more than ever—but sometimes, it makes it easier to feel alone. This conundrum is at the heart of Wild Goose Dreams at the Public Theater, an alternately gentle and hard-hitting look at life and loneliness in the digital age.

Peter Kim (left) as Guk Minsung and Michelle Krusiec as Yoo Nanhee in Hansol Jung’s Wild Goose Dreams. Top: Kim performs on guitar with chorus members (from left) Jamar Williams, Lulu Fall and Jaygee Macapugay.

Written by Hansol Jung and directed by Leigh Silverman, Wild Goose Dreams centers on Guk Minsung (Peter Kim), a so-called “goose father,” who lives alone in South Korea while sending money to his wife (Jaygee Macapugay) and daughter (Kendyl Ito) in America, and Yoo Nanhee (Michelle Krusiec), the North Korean escapee whom Minsung meets online and soon begins an affair with. The show spotlights the couple’s fledgling relationship amid their lonely lives: Minsung isolated in a tiny apartment, watching his wife drift away through Instagram posts while his daughter blocks him on Facebook, and Nanhee as a low-ranking government administrator plagued by guilt over the father (Francis Jue) she left behind in North Korea. “We are together because we are alone, and being together paralyzes that terrible feeling for a while,” Nanhee angrily tells Minsung during a fight, though love blooms out of the pair’s initial desire for companionship.

The endearing love story is told with a light touch. The two find peace with each other amid their bleak lives through tender in-person moments and nervous online exchanges, carefully conversing in the slightly stilted English of people speaking a foreign tongue. (“Do you wish to talk about the problem of love?” Minsung asks Nanhee.) But this is no straightforward romance. The play takes place in a world of magic realism, where the understated love story is offset by Nanhee’s dreams of guilt and hallucinations of the father she left behind. These visions are wildly fanciful—penguin costumes (by Linda Cho) are used liberally—yet they grow increasingly antagonistic, as Nanhee fears the consequences of her defection by North Korea’s oppressive regime. “You left us to cross the river. You knew what that meant for us,” Nanhee imagines her parent saying.

“These three aspects of the world of the show—the romance, the Internet and Nanhee’s dream world—collide in both helpful and detrimental ways. ”

The characters’ online lives add another layer, as Nanhee and Minsung’s Internet usage is personified through spoken interjections—“no new emails, no new messages”—and musical interludes (composed by Paul Castles) by the production’s chorus. Performers shout out Internet buzzwords — “Win a free trip to the paradise of your dreams!”, “28 reasons skinny is the new fat!”—before joining in a sung binary code chorus. The tactic is a refreshing alternative to the screened projections other shows use to depict the Internet; using ensemble members acknowledges the humans behind online usernames, and their overlapping and cacophonous voices illustrate the chaotic nature of the average Internet session.

These three aspects of the world of the show—the romance, the Internet and Nanhee’s dream world—collide in both helpful and detrimental ways. The dream sequences and the Internet scenes’ boldness can overpower the gentle tale, and they often take precedence over the love story at the production’s core. An overlong Internet scene at the beginning of the piece gets the storytelling off to a slow start, and Nanhee’s metaphoric visions dominate many of her interactions with Minsung to slightly tiresome effect.

Yoo Nanhee speaks with an imagined version of her father, played by Francis Jue. Photographs by Joan Marcus.

Yet these other elements’ brashness is advantageous as well, demonstrating the outside forces’ weight on the characters and how the digital world and Nanhee’s dreams drive their actions as the show pushes into tragedy. The vibrancy of these worlds builds out the pair’s otherwise solitary existences, showing the vastness of their inner and online lives in contrast to the quietude of their lonely realities. In addition to the play’s various performed realms, Clint Ramos’s scenic design successfully blends loudness and simplicity, transporting the audience to urban South Korea not through elaborate set pieces, but through immersive bright imagery and signage coating the walls of the theater.

The show’s central love story is told effectively by Kim and Krusiec, who bring the show to life through their understated chemistry. Kim brings a sadly sweet eagerness and naiveté to Minsung that’s both endearing and deeply heartbreaking, while Krusiec’s blend of emotional guardedness and smart determination captures Nanhee’s struggle between embracing her South Korean life and holding onto the North Korean one she escaped. Jue’s fiendish sprightliness in his role as Nanhee’s imagined father matches his whimsical dream persona, yet also captures the emotional heft needed when the fantasies turn dark. Though these performers face stiff competition from Wild Goose Dreams’ flashier elements—and sometimes are drowned out by it—their take on this digital, fantastical, yet deeply human tale shows that this story still deserves to rise above the noise and be heard.

Wild Goose Dreams runs through Dec. 16 at the Public Theater (425 Lafayette St.). Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday, with matinees at 1:30 p.m. on Saturdays and Sundays. For tickets and information, visit publictheater.org.

Downstairs

As the novelist Joseph Heller observed, “Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you.” And as the three characters who barely survive Theresa Rebeck’s twisting and twisted thriller, Downstairs, demonstrate, paranoia is merely one indication that someone you know could be harboring bad intentions. Other warning signs include psychopathic tendencies, the inability to separate reality and fantasy, and sheer, anesthetizing dread. Maybe your workmates are dispensing poison, or your husband is not the man you thought you knew, or your sister has had enough. Maybe that pipe wrench would be an effective blunt instrument. Or, maybe it’s just all in your head. Rebeck and her stellar cast keep us guessing through a tense, intermission-less hour and 45 minutes, while simultaneously pondering larger questions involving inheritances of both the genetic and financial variety.

John Procaccino plays Gerry, the controlling husband of Irene in Theresa Rebeck’s Downstairs. Top: Real siblings Tyne Daly and Tim Daly are Irene and Teddy, the sister and brother in Rebeck’s thrilling family drama.

Basements are notoriously the dark room where the bodies are buried, but Rebeck flips the script from the start. With a comfy couch, a coffee-making machine, and a ray of light coming in from a street level window, the downstairs is the only secure space to be had in the house of Irene and Gerry (Tyne Daly and John Procaccino). Finding safety there is Irene’s brother, Teddy (Tyne’s real-life brother, Tim Daly). He is in lost-boy mode, a grown adult wandering the room in his underpants with a glazed expression on his face. He’s had a tough time of late, but just how reliable are his tales of woe and plans for redemption? Given his stinginess with details and his shaky grasp of reality, chances are he is just plain desperate.

None of this is lost on Irene, who genuinely cares about her sibling, fortifying him with this sanctuary as well as with hot meals and desserts from their youth. Their interactions reveal an ominous family history involving an absent father and a cruel, alcoholic mother who left Irene a cash windfall and bequeathed Teddy nothing other than an unstable mind.

Irene, meanwhile, has her own dilemma. Her husband has, over the years, broken her to the point where she has become a hostage in her own home. Her talks with Teddy reveal that Gerry has taken over the finances, denied her the chance to have children and generally terrorized her into submission. The audience first encounters him at the same time Teddy does. With Irene out shopping (at least, we hope she is out shopping and not, perhaps, stuffed in an upstairs closet), the man of the house comes down to give Teddy his marching orders. He is a big guy with a creepy calmness who cannot quite sell the story that it is Irene who really wants him gone. The second time we encounter Gerry, Teddy has indeed made a departure but not before leaving Irene with information she can use to free herself from her living hell. In a wonderfully dark resolution between husband and wife, Gerry goes full psycho, uttering menacing lines like, “You found rat poison in the basement? Maybe I was killing rats.” Irene, though, holds the upper hand, and it is clenching that pipe wrench.

“Warning signs include psychopathic tendencies, the inability to separate reality and fantasy, and sheer, anesthetizing dread.”

Despite such theatrics, Rebeck avoids melodrama and endows her work with patches of poetry. For instance, reflecting on the mechanics of human nature, Irene observes, “There’s that funny thing they say, that all your cells die every seven years. ... You’re a new person, every seven years. So since then, since we were kids, we’ve been new people how many times?” Director Adrienne Campbell-Holt knows when to be subtle and when to be harsh, exploiting the seeds of doubt that, despite what the audience knows to be true, never quite go away. Is Gerry really a madman, or a reasonable fellow with an unstable wife? How is Teddy sure of his sister’s predicament while barely understanding his own? Is Irene a victim of abuse, or does insanity run deep in the family? Late in the play, Teddy is passed out on the couch, and the odds are fifty-fifty that he is either in a happy slumber, or stone-cold dead.

Teddy (Daly) makes an unsavory discovery. Photographs by James Leynse.

Mr. Daly skillfully walks the line between victim and savior. Ms. Daly, returning to the Cherry Lane, where her theater career began in 1966, pulls off the admirable feat of bringing depth to a character who has been beaten numb. And Procaccino is bone-chilling, chewing the scenery when called for, demonic when up against the wall. Among the many clever touches in the scenic design by Narelle Sissons, the smartest is the landing near the top of the staircase that leads from the unseen upstairs down to the basement. It serves as a beacon. When we spy Gerry, visible from the waist down, pausing there, the tension mounts. When a pair of female legs come into view, there is a palpable sigh of relief that Irene is still on her feet.

Theresa Rebeck’s Downstairs runs through Dec. 22 at the Cherry Lane Theatre (38 Commerce St.) on a schedule as twisted as its plot. Evening performances are at 8 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday, with an additional performance at 8 p.m. Dec. 2 but none on Dec. 20. Matinees are at 2 p.m. Wednesday and Saturday and 3 p.m. Sunday but there are no matinees on Nov. 28 or 30, or on Dec. 12. For ticket and information, call (212) 352-3101 or visit primarystages.org.

Life x 3

Life x 3, Yasmina Reza’s high comedy about a dinner party gone seriously wrong, falls almost midway between her breakthrough hit Art (1994) and the equally acclaimed God of Carnage (2005). That may partly explain why this 2000 play has remained in the shadows, but on the surface it also seems a mere artistic exercise for the Iranian-born French playwright. As the title implies, Life x 3 examines the same evening from three different angles, but it also comments on its characters’ stresses and petty conflicts in relation to the universe. The excellent production is a welcome, if unusual, revival by the New Light Theater Project, which usually presents new plays.