Popcorn Falls, James Hindman’s new two-hander, begins with a burst of energy. With “O Fortuna” from Carmina Burana blaring through the speakers, the performers, Adam Heller and Tom Souhrada, sprint about the stage preparing the props, costumes, and set pieces for the screwball play to follow. Indeed, the mad dash is intended to set the scene for the evening’s romp in which the two actors play a combined total of 21 different characters.

What the Constitution Means to Me

Like many teenagers in the late 1980s and early 90s, Heidi Schreck was obsessed with Patrick Swayze. Unlike many teenagers, Schreck earned money for college by winning speech contests in American Legion halls across the United States. What the Constitution Means to Me, Schreck’s reimagining of those speeches, is less about America’s founding document than the country’s history of violence against women. The play’s humdrum title is misdirection. What the Constitution Means to Me is feminist agitprop autobiography masquerading as civics lesson, not blurring the line between the personal and the political but denying that such a line ever existed.

Mike Iveson as a member of the American Legion in What the Constitution Means to Me. Top: Heidi Schreck makes the political personal.

The play plants its femme-centric flag with preshow songs like Ariana Grande’s “God Is a Woman” and Dua Lipa’s “New Rules,” with the lyric “I keep pushin’ forwards but he keeps pullin’ me backwards.” These he’s dominate the stage, with row after row of photos of pale, stale, and male veterans lining the walls of Rachel Hauck’s Legion Hall set, reconstructed more from Schreck’s memory than precise research. The play is not anti-veteran, but neither does it equivocate about the primary source of violence against women. In fact, Schreck implicates the whole audience in this violence, or at least invites them to consider their complicity, by pretending to be her American Legion onlookers. “You are all men,” she says, though Schreck’s ultimately hopeful play implies that the condition is not terminal, and might even be treatable; Mike Iveson, who joins Schreck onstage as the competition arbiter, eventually removes his costume to reveal his “true” self, which Schreck hopes can represent “positive male energy.”

What the Constitution Means to Me is built on such fluctuations of identity, with Schreck slipping in and out of character as her younger and current selves. Her conversational introduction engenders an easy and immediate intimacy with the audience. Raised to be “psychotically polite,” Schreck is a generous, responsive entertainer, tailoring her performance to the crowd’s humor and at one point waiting for an overwhelmed patron to leave before continuing a story of abuse. Hers is no vanilla presence, however; after a few more walkouts, she conceded that “those of you who are still here seem to be nice.” Schreck spends most of the evening playing her current self, so What the Constitution Means to Me might be more appropriately termed a stand-up routine than a play.

This obscuring of identity, so well-suited to the theater, at once broadens and limits the play’s scope. The stories of Schreck’s great-grandmother, a mail-order bride from Germany who died of “melancholia” in a mental institution at age 36, and her mother, who was repeatedly sexually abused, are affecting and horrifying. Yet it is never apparent if Schreck is speaking as herself or as the version of herself created for this play, and when she conjures tears at her ancestors’ trauma, it’s hard to not feel like the audience is being taken for a ride, or at least instructed how to feel.

Rosdely Ciprain debates the Constitution’s virtues. Photographs by Joan Marcus.

The play’s coup is the inclusion of a high-school-age debater from New York City; Rosdely Ciprain and Thursday Williams alternate in the role. Though the debater doesn’t enter until late in the show, her arrival brings the hope that allows Schreck to cope with the “staggering facts of violence against women.” Schreck and her young companion engage in playful scripted debate, again uneasily walking the “real”/performed divide, but the vision of young, diverse womanhood leading the charge is undeniably moving.

To call What the Constitution Means to Me timely is to state the obvious, yet it’s sheer theatrical serendipity that this play, long in development, should come out right when the confirmation of a new Supreme Court Justice is affirming our country’s ugliest tendencies. There is no period in the history of this country, though, in which its anti-patriarchal message would not be timely; that’s the whole point. Schreck demonstrates again and again that women’s bodies, just like those of African-Americans and all immigrants deemed “bad,” have been left out of the Constitution from the beginning. At the end of the play, Schreck and the young debater model community-building by asking each other questions submitted by audience members. Yet despite the evening’s timeliness, its optimism feels increasingly ingenuous. The play’s final line, “Are we done?” spoken by the young debater as a comedic throwaway, is chilling in ways the play neither intended nor can do much about.

Heidi Schreck’s What the Constitution Means to Me plays through Oct. 28 at New York Theatre Workshop (79 E. 4th St.). Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Tuesdays through Thursdays and 8 p.m. on Fridays and Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays, with a special 7 p.m. closing performance on Oct. 28. For tickets and information, visit nytw.org.

High Noon

With Network and To Kill a Mockingbird just around the corner, it seems like a good time to question the practice of putting classic movies onstage. Can the theater bring any added value to such highly regarded works? Certainly it can reshape them: Network, it seems, will come with a lot of multimedia doodads and whatever else director Ivo van Hove drags into it, and Mockingbird will feature adults in the kids’ roles. Whether those shows will equal the impact they had on the big screen remains to be seen. Meantime, downtown, Axis Company is also having a go at screen-to-stage, with its adaptation of High Noon.

Final Follies

If you thought you knew A.R. Gurney, you’re in for a bit of a surprise. Final Follies, Primary Stages’ collection of three Gurney one-acts, reveals facets of the late, beloved playwright that steer clear of the collective impression of him. Yes, WASPs frequent the stage, though not exclusively, and Gurney is concerned as usual with questions of status, repression, and traditions passed on from generation to generation. But he wanders into what seems very un-Gurney territory—with uneven but often beguiling results.

The Evolution of Mann

Despite the title, the lead character in The Evolution of Mann, a busy and lovelorn new musical from Douglas J. Cohen and Dan Elish, does not rise to a higher plane of existence. Rather than evolve, Henry Mann, played with his broken heart on his sleeve by Max Crumm, falls victim to his own choices as well as to the whims of those he matrimonially pursues. If, over the course of 90 minutes and a dozen songs, he ultimately finds a ray of hope, it is the females around him who elevate his consciousness, if not his likability.

Uncle Romeo Vanya Juliet

Bedlam, the estimable theater company founded in 2012, has a reputation for reinvigorating classic texts with a combination of raw energy and incisive interpretation. At its best, Bedlam distills a work to its bare essence using a small cast to reveal the play’s soul, which apparently had always been hiding in plain sight. Their production of Saint Joan, for instance, employed just four actors and revealed the vigor and immediacy within Shaw’s verbosity. The same four actors performed Hamlet as a giddy romp that also succeeded in finding new depths of pathos and urgency. And their adaptation of Sense and Sensibility managed to plumb the theatricality from Jane Austen’s 19th-century novel with 21st-century showmanship.

Bedlam’s latest production, Uncle Romeo Vanya Juliet, described in the show’s publicity as a mash-up of Uncle Vanya and Romeo and Juliet, takes a different approach. Rather than burrowing into the separate plays for new subtextual insights, the adaptation by Kimberly Pau looks outside of the texts for inspiration. The dramaturgical merging attempts to show how the classic works complement each other through their über-textual parallels. The final result, unfortunately, is as ungainly as the show’s title. The production ultimately numbs Chekhov’s aching anguish and neuters Shakespeare’s romantic poetry.

Susannah Millonzi as Sonya and Eric Tucker as Astrov in Kimberly Pau’s Uncle Romeo Vanya Juliet. Top: Zuzanna Szadkowski as Yelena/Juliet and Edmund Lewis as Vanya/Romeo.

Actually, the mash-up designation is rather misleading. While one might expect this appellation to be a classical cocktail mixed with equal parts Vanya and equal parts Romeo and Juliet, the primary focus is essentially on the former. Pau has provided a script that is a generally faithful version of Chekhov’s play with just two eliminated characters (Vanya’s mother and Sonya’s former nanny), but the rest of the existentially afflicted individuals are all present.

For the first two thirds of Uncle Romeo Vanya Juliet, directed by Eric Tucker, audiences can expect a fairly straightforward interpretation of Chekhov’s masterwork. For those unfamiliar with the plot, the lives of Vanya (Edmund Lewis) and Sonya (Susannah Millonzi) are thrown into turmoil with the arrival of Sonya’s father and pedantic professor, Serebryakov (Randolph Curtis Rand), and his young wife, Yelena (Zuzanna Szadkowski). Astrov (Tucker), the neighboring doctor and dabbler in botany, has become a permanent fixture in the home, and his passionate love for Yelena wreaks emotional havoc on the household.

Vanya also loves Yelena, and both Sonya and Yelena love Astrov, and although no one dies as a result of star-crossed passions, their fates are even worse: except for the haughty professor, the characters will presumably live in eternal misery and loneliness.

In Bedlam fashion the proceedings are punctuated with cheeky anachronisms and choreographed chaos. When Vanya threatens Serebryakov with a gun, for example, the characters scream that he is “going postal,” and Yelena has a momentary daydream/dance break underscored by the 1980s lovers’ anthem, “Total Eclipse of the Heart.” Moments of emotional turmoil are highlighted with actors forcefully rolling set pieces into and out of the playing space. (John McDermott’s scenic design, which playfully creates a Russian estate with moveable birch trees, office furniture, and an iconic samovar, is spot-on.)

Tucker and Szadkowski. Photographs by Ashley Garrett.

The Romeo and Juliet tangents offer little in the way of emotional or intellectual illumination. At times, there are moments of cleverness, such as in a reference to Vanya’s dream. This prompts Astrov to metamorphose into Mercutio and recite his well-known Queen Mab monologue. There is also an extended riff late in the play in which Vanya fantasizes about killing Serebryakov, and the characters assume an alternative reality. Vanya/Romeo and Yelena/Juliet are romantically tragic in ways that undercuts the quotidian tragedy that Chekhov presents.

If the amalgamation does not effectively serve Chekhov’s and Shakespeare’s works, the five-member ensemble (with an on-stage musician, John Coyne, who masterfully accompanies the cast in periodic Russian folksongs) tears into the material. Alternating between rough-and-tumble acting and broad comedy, each actor also has quiet moments to show the sense of solitude just under the surface.

Les Dickert’s impressive lighting (with a special nod to the birch trees with red fairy lights) and Charlotte Palmer-Lane’s mix of contemporary and period-inflected costumes (including putting Yelena/Juliet in a white wedding dress for most of the second act) provide a waking dreamlike quality to the proceedings.

Chekhov purists might be more inclined to see the current production of Uncle Vanya across town at Hunter College. Richard Nelson’s spare, quiet production seems more radical in its simplicity. The Bedlam production needlessly and regrettably complicates the play with its infusion of dramatic schizophrenia.

Uncle Romeo Vanya Juliet plays through Oct. 28 at A.R.T./New York Theatres Mezzanine Theatre, 502 W. 53rd St. Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Tuesday and Thursday through Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday. For a performance calendar and tickets, visit bedlam.org.

A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur

If you didn’t know that A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur was by Tennessee Williams, you might easily guess it. When the critic John Mason Brown reviewed A Streetcar Named Desire in 1947, he noted that play’s similarities to The Glass Menagerie: “Mr. Williams’ recurrent concern is with the misfits and the broken; with poor, self-deluded mortals… If they lie to others, their major lie is to themselves. In this way only can they hope to make their intolerable lives tolerable. Such beauty as they know exists in their dreams. The surroundings in which they find themselves are once again as sordid as is their own living.” Brown might have written the same words about Creve Coeur, first produced in 1979.

Its two main protagonists are Dorothea (“Dotty”), a young teacher, and an older woman, Bodey, from whom she rents a space in a cramped apartment (vividly evoked by Harry Feiner as a warren of furnishings with a smash of colors). The other two characters are Helena, a well-dressed, determined woman with a plan to upset the arrangement and Miss Gluck (Polly McKie), an emotional mess in a bathrobe. Her mother has recently died, and she thinks her upstairs apartment is haunted and keeps dropping down to see the sympathetic Bodey.

Kristine Nielsen (left) is Bodey and Jean Lichty is Dotty in Tennessee Williams’s A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur. Top: Nielsen and Lichty with Annette O’Toole as Helena.

Produced by La Femme Theatre Company, “dedicated to the exploration and celebration of the universal female experience,” Creve Coeur doesn’t have the more experimental elements of Williams’s late plays, nor even the framing device of A Glass Menagerie—although Creve Coeur is set in St. Louis, in the 1930s—but the delusions are present.

Dotty (Jean Lichty, founder of La Femme) is a struggling schoolteacher who rents space in a cramped apartment as she’s waiting for something better to turn up, specifically a phone call from Frank Ellis, the flashy high school principal who has taken her out.

Bodey (Kristine Nielsen), the landlady, is a dynamo who cooks, sympathizes and tries to interest Dotty in her brother, Buddy. Bodey has planned a regular Sunday outing for Creve Coeur, where there’s an amusement park, and she hopes Dotty will go. Buddy will be there.

Dotty knows that Bodey is playing matchmaker, despite Bodey’s denials, and she tries to emphasize her lack of interest in Buddy: “He simply isn’t a type that I can respond to…In a romantic fashion, honey. And to me, romance is—essential.” Fans of Williams can foretell there’s going to be heartbreak (crève-coeur is French for “heartbreak”), even if Dotty is shrewd enough to see past Bodey’s machinations, in Williams’s lyrical description of a grim future: “You’ve been deliberately plotting to marry me off to your brother so that my life would just be one long Creve Coeur picnic, interspersed with knockwurst, sauerkraut—hot potato salad dinners.”

Nielsen with Polly McKie as Miss Gluck. Photographs by Joan Marcus.

In spite of the lyricism, though, Williams’s extended back-and-forth between the two women feels laborious, and director Austin Pendleton, who does a fine job otherwise, makes a crucial mistake by having Bodey read a notice in the newspaper and throw it to the ground, unnoticed by Dotty; you can almost predict in the first moments that the paper has an engagement announcement involving Ellis. The action hangs like an albatross on the already repetitious dialogue of the first half.

Things pick up when Helena arrives. Annette O’Toole is a smartly dressed social climber who teaches at Dotty’s school; she has found an apartment but needs Dotty to share expenses. It’s the clash between Helena and Bodey that provides the interest.

From the start, the elegant, supercilious Helena is thwarted by Nielsen’s tough broad, and you can’t help but root for Bodey as she prevents the pushy intruder from walking all over her—even suggesting a possible physical opposition. Nielsen expertly navigates the kindness, toughness and self-delusion of her character while finding unexpected comic moments. O’Toole, too, though easy to dislike, makes Helena more than a mere snob; she is also a woman with dreams who is too proud to admit she needs a helping hand. Lichty charts Dotty’s slow disintegration of confidence and her growing fragility and frustration, but her Dotty never implodes, even when her hopes are dashed. McKie, in a part that requires little English but expertly accented German, excels in making the weepy Gluck memorable.

Ultimately, it’s the actors who refresh the tired themes of this late Williams drama. Williams fans who rarely have the chance to see his lesser plays in good productions will welcome this opportunity.

La Femme’s production of A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur plays through Oct. 21 at Theatre at St. Clement’s (423 West 46th St.). Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Wednesday and Thursday and at 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Saturday and 3 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are $55–$99 and may be purchased by calling (866) 811-4111 or visiting lafemmetheatreproductions.org.

Experimenting with Katz

It’s getting a little late in the day for a contemporary coming-out comedy. Isn’t that battle pretty much over, and aren’t plays like Gemini and Torch Song Trilogy period pieces by now? That said, David Adam Gill gets a fair amount of comic mileage out of Experimenting with Katz, his “new comedic play” about, shades of Albert Innaurato or Harvey Fierstein, Michael Katz (Paul Pakler), a youngish gay man with self-esteem issues, romantic issues, and severe mother issues. Gill hasn’t quite merged his characters and themes into a cohesive whole, and he needs to acquaint himself with the Delete key—Katz, small as it is, runs more than 2½ hours. But he knows how to make us laugh, and, a few contrivances notwithstanding, care a little, too.

You and I

Maitland White, the protagonist of Philip Barry’s unjustly forgotten comedy You and I, has a blissful marriage, children on the cusp of adulthood and a highly remunerative corporate job. To all appearances, he’s the world’s most contented man, sharing a luxe existence with his loving family in the roaring days before the stock market crash of 1929. What no one around him knows is that Matey retains the great ambition of his youth. And, in middle age, that secret urge—to be a professional painter—is becoming increasingly insistent.

This Is When We Rest

An asteroid collides with Earth in just over an hour. You are at an apartment party in New York City with eight people whom you know from various stages of your life. What do you discuss with them? What is going through your mind? Do you have any regrets? These are the large, existential questions brought forth by Part Two of Live In Theatre’s This Is When We Rest, an apocalyptic theater experience designed by Leland Masek that combines Live Action Role Play (LARP) gaming and participatory theater.

Spin Off

Bernard Pomerance, who died last year at age 76, is best known for having written that brutal little lesson in humanity, The Elephant Man. That play’s best line, “We have polished him like a mirror, and shout hallelujah when he reflects us to the inch,” nicely encapsulates the playwright’s concerns over the societal tendency to perform acts of charity for the sake of the giver. But, as is discovered in the wandering world premiere of Spin Off, which was drafted in 2003 and revised in 2006, Pomerance’s thought processes were not always so tidy.

Beep Boop

Richard Saudek, the creator and performer of the one-man show, Beep Boop, is a self-confessed “idiot who likes to make faces at himself in the mirror.” If his program bio is to be believed, “when he was ten, he ran off to perform in the circus as a young clown, then left the circus at the age of sixteen to pursue other theatrical stuff, such as commedia dell’arte in Florence; improv in Chicago; stilt-walking in Shanghai; burlesque opposite Steve Buscemi; and has portrayed madmen and fools for over a decade all over NYC.” Whether Saudek’s resume is 100 percent accurate or not, one thing is certain: his kind of rigorous talent does not happen overnight.

The True

To anyone who grew up in the Albany area before cable television (or, as I did, in western Massachusetts, served only by Albany stations), the name Erastus Corning was inescapable. For 35 years he was the Democratic mayor of the city, and nightly broadcasts featured him prominently. Sharr White’s marvelous new play The True makes Corning (Michael McKean) a central character in a story of what political parties and machine politics once were and, by contrast, what they have become. It has scope, intelligence and terrific writing.

The Revolving Cycles Truly and Steadily Roll’d

A teenage boy goes missing, and his foster sister embarks on an urban odyssey to track him down in the Playwrights Realm’s brazen production of The Revolving Cycles Truly and Steadily Roll'd. Early-career dramatist Jonathan Payne unleashes a Pandora’s box of theatrical devices, including symbolically named characters, direct audience interaction, screen projections, a live-streaming cellphone, and actors not only breaking the fourth wall but breaking character as well. Veteran off-Broadway director Awoye Timpo molds it all into a bracing panorama of societal failures amid institutional racism. That is, until the final scene when, with the play’s momentum waning, she and Payne risk one last gambit that unfortunately swallows up all that came before it.

James and Jamesy in the Dark

James and Jamesy in the Dark is an extraordinary piece of theater that fits no mold but its own. It draws on many sources—or pays homage to them—but it is a unique, thought-provoking delight. Two gifted physical performers (in whiteface and dressed top-to-toe in gray outfits, including gloves) embody the title characters. Eventually, the audience comes to recognize the taller one as Aaron Malkin’s more phlegmatic James and the shorter, more emotionally fragile one as Alastair Knowles’s Jamesy.

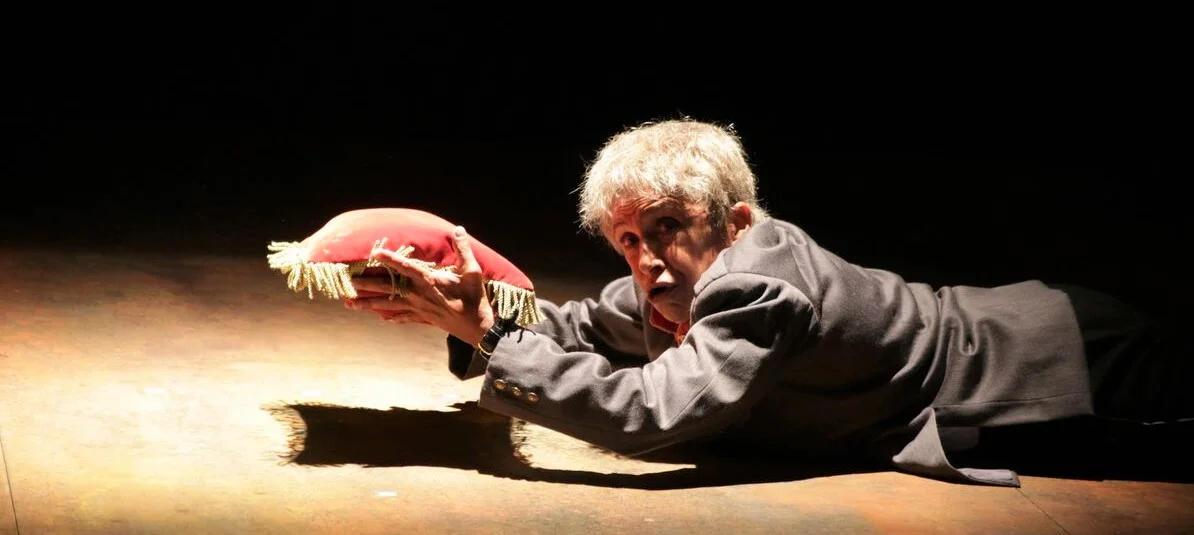

The Emperor

The Emperor, based on a book of interviews with elderly government employees in the court of Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, is every bit as intellectual a docudrama as it sounds, mostly lacking emotional engagement. It’s more like history presented with interspersed activity as window dressing. Those who attend are likely to do so because of actress Kathryn Hunter’s reputation rather than a burning desire to hear about Selassie, who died in 1975.

The Naturalists

The three principal characters of Jaki McCarrick’s drama The Naturalists are refugees from a society that, in their view, damages the earth and is toxic to the human heart. The time is 2010; the place, the Republic of Ireland’s Border Region. Brothers Francis and Billy Sloane (John Keating and Tim Ruddy) have settled into middle age as small-time farmers, accustomed to being alone with each other and the glorious landscape around them.

Heartbreak House

The Gingold Group in New York thrives on the plays of George Bernard Shaw. Each month, artistic director David Staller assembles a cast for readings of them, but far too seldom is a Shaw work fully staged in New York. As Staller’s production of Heartbreak House shows, Shaw is still timely, almost uncannily so. Set during World War I, the play is an examination of the British nation; its characters encompass rich and poor, young and old, gentry and businessmen and clergy. In the view of the shrewd old socialist, it is, in the words of heroine Ellie Dunn, a “house without foundation—I call it Heartbreak House.”

Hurricane Party

A dangerous storm, Evelyn, is bearing down on the characters in David Thigpen’s Hurricane Party, but the more immediate threat to their existence arises from their own behavior. Opening on a steamy sex scene, Maria Dizzia’s production is suffused with an eroticism often associated with a hot climate, akin to that of the film Body Heat. The characters in the scene, Dana and Macon (Kevin Kane and Sayra Player, respectively), are entering middle age and at a crossroads. Each is married to another person, and, in Macon’s case, it’s Todd, Dana’s best friend. She and Dana have been conducting an affair for “two years and three months,” and now he plans to spirit her away within the week for a future together.

Be More Chill

The Broadway-bound Be More Chill is a Black Mirror–meets–Mean Girls musical with a cult following that has propelled it from its 2014 premiere at the Two River Theater in Red Bank, N.J., to an Off-Broadway run. The power of social media and an obsessive teenage fan base took this little-known show and made it the second most mentioned musical on Tumblr in 2017 (behind Hamilton).