Old Testament history has been amply recreated on the stage and in film—enslavement in Egypt, the Hebrews’ 40-year desert trek to Mount Sinai, the Ten Commandments, transmission of Jewish laws, and a passionate yearning for the Promised Land. In Two Jews, Talking, playwright Ed. Weinberger loosely and innovatively paints both this saga, a “revisionist” desert adventure, and its cemetery-centered finale, with a very broad brush. He does so with the aid of veteran actors Hal Linden and Bernie Kopell, whose characters face off against each other theologically and temperamentally yet find comfort in each other’s company.

The Near Disaster of Jasper & Casper

It can’t be easy to invent a brand-new fairy tale; even James Lapine and Stephen Sondheim had to rely on the old favorites. But here comes Jason Woods, not only cobbling together an entirely original fantasy with The Near Disaster of Jasper & Casper, but performing all the parts, with distinctive voices and personalities for all the characters. Woods may seize on some familiar plot points, and he’s not always tidy: “Jasper and Casper” don’t rhyme perfectly with “Disaster,” as he seems to have been aiming for. But he knocks himself out to engage the audience.

Macbitches

Sophie McIntosh’s Macbitches is proof positive that some of the most exhilarating theater in New York City is being staged in Off-Off-Broadway houses. McIntosh’s 85-minute piece dramatizes what happens when Hailey (Marie Dinolan), a freshman acting major, is unexpectedly cast in the plum role of Lady Macbeth, and Rachel (Caroline Orlando), the queen bee of a college theater department in Minnesota, is left with big bruises on her ego.

On That Day in Amsterdam

On That Day in Amsterdam begins on a morning in 2015, after two young men have hooked up at a dance club in the Dutch metropolis. One of them, Kevin (Glenn Morizio), an American of Filipino extraction, is impatient to depart: he has a flight back to America later in the day, and he feels no emotional connection. The other, Sammy (Ahmad Maksoud), hopes to know Kevin better and nudges him to have breakfast. A heavy snow delays Kevin’s trip, and what ensues in Clarence Coo’s emotionally reverberating play expands to far more than a gay love story: it is a moving drama about life’s fleeting encounters, loss, nostalgia, home, art, and memory, told in scenes that skip through centuries.

Katsura Sunshine’s Rakugo

Katsura Sunshine’s Rakugo is a fresh and funny solo show in which the director and star, Katsura Sunshine, spins yarns with entrancing charm in the ancient Japanese comic storytelling tradition known as rakugo. It is a pleasure to come across a piece that deals, wittily and delightfully, with a little-known dramatic art form.

The Butcher Boy

Whoa! At the ends of both acts of The Butcher Boy, the Irish Rep’s new musical adapted from Patrick McCabe’s 1992 novel, such unsettling things happen that you’re forced to revisit everything that preceded them, assessing how much was fact, how much was fantasy, and whether or not we should trust our narrating protagonist, Francie Brady (Nicholas Barasch, and we shouldn’t). The Butcher Boy isn’t comforting or reassuring or lovable, and it won’t send you out whistling a happy tune. But, and this puts it ahead of much of the current pack, it isn’t stupid.

The Panic of ’29

The Panic of ’29 isn’t deep. It hasn’t much on its mind, except camp silliness and an encyclopedic knowledge of old-movie tropes, mixed up and scrambled and spilled out on the modest 59e59 stage. Graham Techler’s loose comedy is a Less Than Rent production, which claims in the program that its mission is “examining the relationship we have to capital and the web of injustices that stem from an allegiance to profits over people.” We don’t get a whole lot of that, except in the broadest terms, but we do get some zingy one-liners and a lively troupe of players. The first half-hour or so of The Panic of ’29 is rather delightful. And then it just goes no-damn-where.

Under the Dragon’s Tail

On the lam criminals, a would-be king living as an exiled stoner, an untethered cosmonaut, and a pair of lovers sorting through the detritus of a terminated relationship—are the characters populating Isaac Byrne’s Under the Dragon’s Tail. Byrne also directs the quartet of one-acts that are not always in perfect harmony, but as a quadriptych, they intriguingly show the ways in which elements of mythology, metaphor, and symbolism can give order to the chaos of the contemporary world.

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof features roles that are (pardon the expression) catnip to adventurous actors. This land mine of a play premiered in 1955, a year that, in retrospect, seems the apex of Williams’s success. The playwright’s career took off with The Glass Menagerie in 1945, followed by A Streetcar Named Desire in 1949, and continued for 28 years after Cat, until his death in 1983. During a long literary decline, he wrote a number of lesser, though admirable, plays, but even the best of those don’t measure up to his depiction of the Pollitts, a clan of nouveau riche Southern strivers squabbling over “twenty-eight thousand acres of the richest land this side of the valley Nile.”

Sex, Grift and Death

Potomac Theatre Project’s Sex, Grift and Death, an evening of one-acts by British playwrights Steven Berkoff and Caryl Churchill, captures the brutal nature of sex, financial survival, death, and illness. The lively cast uses a mixture of British and American accents that work for the sensibility of each piece.

Mister Miss America

Neil D’Astolfo’s Mister Miss America provides many pleasures beyond its nifty title, even though the material treads some pretty familiar ground. In the solo show, the beauty pageant obsessions of gay hero Derek Tyler Taylor (D’Astolfo) take center stage. DTT wants to share the story of his attempt to break the gender barrier at a beauty pageant in southwestern Virginia, where the contestants mostly hail from obscure burgs, such as Bristol, Galax, Martinsville and Radford, and the announcer uses descriptions like “She’s hotter than your pappy’s pistol!” as an introduction.

Reverse Transcription

For theater aficionados, the summer visits of Potomac Theatre Project to the Atlantic Theater are bracing—weighty pieces rather than fluffy fare. British writers, often well-represented, comprise one evening this year, but two American plays comprise the second. A revival of Dog Plays, a 1989 one-act with snapshot scenes that focus on the AIDS crisis, is by Robert Chesley, who wrote it after receiving “the diagnosis.” (He died in 1990.) It has been dusted off and paired with a new play, A Variant Strain, by writer-director Jim Petosa and Jonathan Adler, that is indebted to the older work.

Richard III

In William Shakespeare’s Richard III, the title character is a hunchback whose anger is fueled because he feels like an outcast. His quest for power becomes a form of revenge. Under Robert O’Hara’s direction, Richard III for the Public Theater is loose and playful. Actress Danai Gurira, in the gender-swapped title role, is sinewy and tiger-like. As Richard, she pounces, manipulates, smiles, grins, and grimaces: a shape-shifter who manipulates others.

Hamlet

“If a work is quite perfect,” wrote W.H. Auden about Hamlet, “it arouses less controversy and there is less to say about it.” Across four centuries, critics have found plenty to discuss in this longest of Shakespeare’s plays (also one of his most frequently performed). Auden is prominent among those viewing it as severely flawed. Director Robert Icke has joined the colloquy with an absorbing stage production, now at the Park Avenue Armory, that handles the script’s ostensible defects with aplomb and, in so doing, refutes T.S. Eliot’s suggestion that Hamlet is an “artistic failure.”

Prince Charming, You’re Late

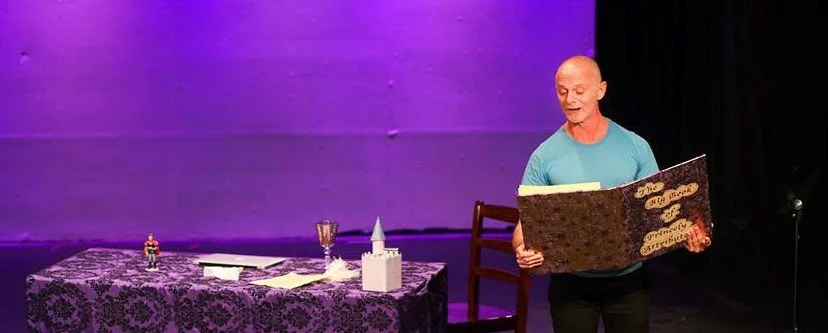

The title of Billy Hipkins’s solo show promises lighthearted fun, and the actor often has a twinkle in his eye as he performs it. However, in spite of the elfin charm of Hipkins himself—a sixtysomething gay man who has worked in theater as a dresser and occasionally an actor—Prince Charming, You’re Late strikes many of the darker notes of a fairy tale by the Grimm brothers.

Epiphany

Anybody who remembers the 2000 Broadway musical adaptation of James Joyce’s The Dead would not be surprised to learn that Joyce’s story inspired Brian Watkins to write Epiphany. The productions look similar: set in a somberly lit room with a large rug in the center, a piano off to one side and multiple tables around. And in Epiphany, just as in The Dead, a group of people gather for a wintertime party in the home of someone named Morkan.

Chains

Elizabeth Baker wrote her first full-length play, Chains, at 32, and after it premiered in London in 1909, critics hailed a “new playwright of unmistakable dramatic genius.” But despite many plays that followed, success in London did not come again for Baker. And so Chains fits into the Mint Theater Company’s mission to “find and produce worthwhile plays from the past that have been lost or forgotten.” That mission is fulfilled in remarkable fashion in director Jenn Thompson’s lucid, moving, and exquisitely acted production, which feels both grounded in a specific historical and cultural milieu and yet also relevant today.

Yes! Reflections of Molly Bloom

James Joyce’s Ulysses is a brilliant but dense and sometimes inaccessible work. Aedin Moloney’s solo performance in Yes! Reflections of Molly Bloom is adapted from Molly's “Yes!” soliloquy at the end of Joyce’s novel. Co-created by Moloney and acclaimed Irish author Colum McCann, the show is a remarkably ambitious collaboration, a welcome contribution to understanding the complexities of Molly Bloom (wife of Ulysses’ protagonist Leopold “Poldy” Bloom), and a consummate one-woman show.

The Orchard

After squandering her inheritance as an expatriate in Paris, Lyubov Ranevskaya, protagonist of Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, comes home to Russia to discover that the old order, so favorable to the haute bourgeoisie, has been scrambled by burgeoning social mobility. Unable to meet the carrying charges on the family estate, Ranevskaya (Jessica Hecht) and her brother Gaev (Mark Nelson) dither rather than addressing the double whammy of altered personal circumstances and a transformed national culture.

The Bedwetter

Six months ago the Atlantic Theater presented Kimberly Akimbo, the musical tale of a 15-year-old girl whose young mind is trapped in a quickly aging body. Now, with the premier of The Bedwetter, it offers up the story of Sarah (Zoe Glick), a 10-year-old girl with a troubled, adult mind trapped in a child’s body that is always letting her down. And though Kimberly is headed toward an early death while Sarah advances toward certain fame, it is the latter character who wants our sympathy. She struggles, however, to fully earn it. In this uneven production, as director Anne Kauffman has discovered, a depressed kid with a foul mouth makes for a problematic protagonist.