Hugh Leonard’s Da is a painful coming-of-age story being given an engaging and rare revival by the Irish Repertory Theater in its temporary home at DR2 Theatre off Union Square.

Set in a rural town in Ireland, Leonard’s 1978 Tony winner deals with Charlie, a middle-aged man who has returned to his family home after the death of his father. The memories he has are painful, and it’s clear immediately in Charlotte Moore’s production that Charlie feels some relief at the recently severed tie to his father. But Da isn’t done with his son: his ghost, a boisterous and peremptory Paul O’Brien, shows up to harangue and browbeat Charlie. And Charlie, for his part, feels resentments bubble up in him once again. As the play unfolds, one learns about the origins of their friction, as well as Charlie’s adolescence and working life. He is, in fact, an adoptive son to Da and his Ma (Fiana Toibin).

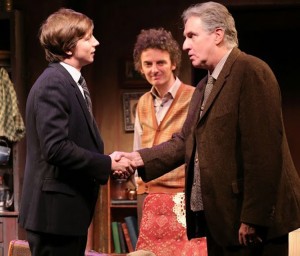

Clues come early on about how difficult Charlie’s life was, as the family prepares for the arrival of a Mr. Drumm who will interview Charlie for a job. There’s a battle over the shirt that Charlie is supposed to wear. (Adam Petherbridge plays the younger Charlie with a mixture of rebellion and Catholic guilt, while Ciarán O’Reilly shines as the more confident and calmer adult observing his life.) He doesn’t want to wear the one that his mother has patched, and his resistance causes a squabble and earns him a slap.

After Sean Gormley’s thin-lipped, priggish Mr. Drumm arrives, Da, though warned to speak minimally, launches into praise of Hitler. (Some Irishmen supported Hitler because he was at war with their historical enemy, England.) Drumm, judgmental and bloodless, has nothing but contempt for Da, and he expresses it bluntly. Drumm offers Charlie a job nonetheless, with the warning that he shouldn’t stay in it too long—a warning that Charlie, a budding writer, doesn’t heed for more than a decade. A nice irony is that Drumm, unsusceptible to sentiment, gives Charlie sounder advice than his parents offer: “You’ll amount to nothing until you learn to say no.”

Leonard’s story slips from memory to the present and back, sometimes a bit strangely: older Charlie doesn’t merely watch his younger self in scenes—they converse about what’s going on, with the older self advising the younger. O’Brien’s Da is by turns morose, cheerful, overbearing, and proud, and it’s clear he will never be a figure his son will worship. In spite of the cozy warmth suggested by James Morgan’s crockery-filled parlor, this autobiographical play is also rife with unhappiness, stupidity, and emotional abuse.

Leonard’s rich language— “Old faces. They’ve turned up like bills you thought you’d never have to pay”—gets full weight from an excellent cast. Although men are the focus, two actresses in smaller parts make the most of their single scenes. Nicola Murphy plays Mary Tate, a reputed good-time girl that Charlie wants but who has more sweetness than he appreciates. Petherbridge is terrific in the scene, alternately bashful and on the make, and Murphy brings true poignancy to poor Mary, initially aloof, then warming to Charlie’s charms. It’s to Leonard’s credit that Charlie, his own stand-in, comes off poorly. As Da’s employer of decades, Kristin Griffith arrives late in the play to deliver a clueless, insulting pittance to the man who has served as her gardener for years, while she eagerly gathers the bounty he has cultivated. Da is ever the apologist for his poor treatment, too proud to claim more than others are willing to give him, and that gripes the older Charlie. It undoubtedly reflects Leonard’s own struggle to find confidence in himself that he is never destined to receive from either father or mother. Yet, as Charlie finally learns, "Love turned upside down is love for all that."

Performances of Da by the Irish Repertory Theatre take place through March 8 at the DR2 Theatre at 103 E. 15th St., off Union Square. Evening curtains are at 7 p.m. Tuesdays and Thursdays and 8 p.m. Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays. Matinees are at 3 p.m. on Saturdays and Sundays.