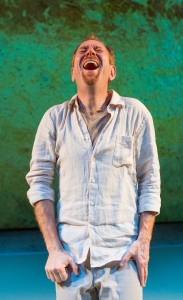

Henry V, the capstone of the Royal Shakespeare Company productions at BAM in this 400th anniversary year of Shakespeare’s death, is a robust staging of a play often regarded as excessively jingoistic. Yet in the hands of director Gregory Doran, it proves far more nuanced than that, a lively and fascinating mixture of the heroism and opportunism that war produces. Alex Hassell inhabits the nobility of Henry V more persuasively than he does the callow prince in the two parts of Henry IV; tall and strapping, he bears the weight of duties with confidence and speaks the renowned speeches thrillingly.

Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2

Shakespeare’s two plays that focus on the reign of King Henry IV are a panoramic view of medieval life. The historical portions, which occur early in the 1400s, take on the question of a monarch’s duty to his country, not least of which is preparing the heir to take over. Ignoring his father’s complaints, Prince Hal (Alex Hassell), Henry’s heir, fritters away his time with lowlifes, notably Falstaff, the fat, rascally knight who is one of Shakespeare’s great creations. The political maneuvering of nobles in rebellion also shapes the narrative about high-born responsibility, leadership and compassion.

Matthew Needham plays Hotspur in Henry IV, Part 1. Top (from left): Antony Sher as Falstaff, Sam Marks as Poins, and Alex Hassell as Prince Hal.

Yet in the tavern scenes and, in Part 2, the country scenes with Justice Shallow and Silence that involve conscription of men for war, the life of the common man is portrayed, more closely reflecting Shakespeare’s own time. From the king down to the lowest conscriptee, the plays provide a broad view of issues that touched Queen Elizabeth I and her subjects.

As Henry IV, Part 1 opens, the king (Jasper Britton) announces plans for a crusade to Jerusalem to retake the city from the Saracens—something he promised in his last speech in Richard II, the chronological predecessor (and also part of the RSC’s visit to the Brooklyn Academy of Music). Quickly, however, Henry is advised of rebels gathering against him: the Earl of Northumberland (Sean Chapman), a former ally in deposing Richard II; his brother, the Earl of Worcester (Antony Byrne); Northumberland’s son, and Lady Percy’s brother, Lord Mortimer (Robert Gilbert). Chief among them, though, is Matthew Needham’s stunningly good Hotspur, a fierce, intemperate warrior whose skill at arms is set against the dissipated life of Prince Hal (Alex Hassell). The trip to the Holy Land must be postponed.

Falstaff, the surrogate father to Hal, is embodied by Antony Sher, a great actor who has nevertheless seldom tackled comedy. Anyone who has seen him in classical roles (Massinger’s The Roman Actor, Marlowe’s Tamburlaine, Marston’s The Malcontent) knows he is a master of the language and a powerful stage presence. As Falstaff, though, something is not quite right. Sher growls a lot to sound dissipated and lumbers around to seem overweight. He can nail the wit, but one has the impression of someone giving a grand performance (and Falstaff is an actor at heart) but not completely inhabiting the character. He’s great fun to watch, but his roistering as Falstaff doesn’t feel natural. Yet there are splendid moments: when he’s trying to connect with his cronies in the darkness on Gad’s Hill to rob some pilgrims, he comes on, stepping slowly and whispering loudly, “Poins? Poins?” to find his compatriot.

Needham (right) with Jasper Britton as King Henry IV. Photographs by Richard Termine.

In a similar way Hassell is not totally persuasive as Hal. Frivolity and callowness don’t sit naturally on him, but as he assumes the gravitas required of a future king, he becomes more persuasive. He gives the speeches clearly but, perhaps because he’s the centerpiece of three plays, there are times when they’re closer to masterly recitation than insightful characterization.

In Part 1, however, Britton, overshadowed in Richard II by David Tennant’s terrific performance, comes into his own as Henry, the usurping king who struggles with his son’s wastrel ways. His halting first lines, “So shaken as we are, so wan with care,” present a royal whose voice literally trembles. And news of Hotspur’s valor against rebels brings joy until his counselor Westmoreland remarks, “It is a conquest for a prince to boast of”—pointing up that Hal should have been leading the victory. The haunted Henry’s grappling with his son’s fecklessness is an important through line for both parts. Part 2, however, also affords Hassell the opportunity to navigate from Hal’s callowness to something that fits the actor better: nobility and valor.

Looser than Part 1, Henry IV, Part 2 also lacks Hotspur. Moreover, the lower-class scenes in it prove a slog. One problem is that Antony Byrne’s Pistol, a swaggering braggart soldier, is a type that may have been funny 400 years ago but grates now. Made up as a yob, with thick black mascara under his eyes and a braid, and dressed in a punkish leather outfit by Stephanie Arditti, he is a tedious figure, offsetting Falstaff’s raillery. Thus, much of the first half of Part 2 is an ordeal, redeemed after intermission by Oliver Ford Davies’ hilarious Justice Shallow, paired with Jim Hooper’s wide-eyed, perplexed Silence.

Hassell as Hal banters with Sher as Falstaff.

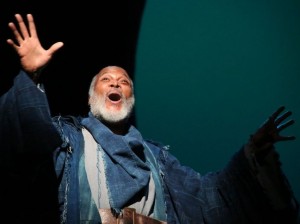

But the most memorable scenes are those with Hotspur. “I can call spirits from the vasty deep,” says Joshua Richards’s Gandalfian Welshman, Owen Glendower, a behemoth in skins and long gray beard, and Hotspur’s in-law. To which Hotspur replies: “Why, so can I, or so can any man/But will they come when you do call for them?” And his scenes with his wife (Jennifer Kirby) are both touching and frustrating; though in love, each tries to connect emotionally with the other and doesn’t always succeed. Other standouts are Sam Marks’s vital Poins and Richards (again) as a red-nosed, dryly comic Bardolph, one of Falstaff’s cronies.

The plays are rich with smart business by director Gregory Doran. With Hotspur on a tear, his father, Northumberland, grabs him by the scruff of his neck and forces him to his knees. Some extended comic business with the serving-boy Francis plays beautifully (and sets up a cameo for Henry V). One clumsy interpolation, however, is Doran’s opening Part 2 with Rumour (Byrne) coming on in modern clothes against a field of projections of #Rumour. It may be intended to parallel gossip on the Internet, but it’s a jarring moment.

Though the first part is the stronger play, together the pair are an indispensable challenge that any lover of Shakespeare’s work will want to experience. They aren’t often done together, and this is an opportunity to hear verse-speaking of a high order and experience outstanding, if not flawless, productions.

The Royal Shakespeare Company’s Henry IV, Part 1 and Part 2 play in repertory with Richard II and Henry V through May 1 at BAM Harvey Theater (30 Lafayette Ave. between Ashland Place and St. Felix Street in Brooklyn). Tickets start at $35. Visit www.bam.org/theater for information.

Richard II

Gregory Doran’s production of Richard II at the Brooklyn Academy of Music is a thunderous start to “King and Country,” the umbrella title for Shakespeare’s histories of three consecutive kings, Richard II, Henry IV (in two parts) and Henry V, visiting from the Royal Shakespeare Company, where Doran is artistic director.

Perhaps “thunderous” is not the right word, since David Tennant’s Richard is never shown at war, but is a frivolous and arrogant ruler as the play opens. He holds himself imperiously aloof in the early scenes, clutching his orb and scepter, but Tennant also finds much humor in the flawed character. The play turns on family relationships, and in describing his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke, the actor terms him “my father’s brother’s son” with slight hesitation between the words, as if Richard is saying to himself, “I’ve got to get this tricky part right.”

Jasper Britton (left) is Henry Bolingbroke and Matthew Needham is his son, Harry Percy, aka Hotspur, in Richard II. Top: King Richard II (David Tennant, right) with Sam Marks as Aumerle.

In order to fund wars to subjugate the Irish, Richard plans to tax the rich. With Bolingbroke banished for feuding with another noble, and his father, John of Gaunt, dead, Richard seizes the inheritance that belongs to his cousin, and goes off to war, where he is unaware of a rebellion at home: Bolingbroke has returned from exile to claim his inheritance and is likely to depose Richard. At the center of the play is the issue of divine right: does the king rule as God’s representative on Earth? Is everything he does God’s will?

Doran plays up the notion of Richard as a divine figure with costume supervisor Stephanie Arditti’s white robe that gives Richard, with very long hair, the look of Christ. The language of Christianity is threaded throughout: “balm,” “water” and “Pilate.” In a climactic scene, Richard himself calls his eventual killer “Judas.” (It’s a key change from Shakespeare, where Richard is slain by Sir Piers Exton, an assassin; this murderer is closer to home.)

The other key relatives in Richard II besides the short-lived John of Gaunt (Julian Glover), who delivers the speech about “this earth, this realm, this England” thrillingly, are the Duke of York, the last of seven sons and also Richard’s uncle, and his son Aumerle (Sam Marks), who becomes Richard’s cousin-with-benefits in Doran’s reading—the homosexual subtext is more forthright here but not unheard-of. Oliver Ford Davies plays the Duke of York with a booming voice, by turns denouncing his nephew Bolingbroke and then backing off. Torn between believing the king is chosen by God, yet finding his regency while the king fights in Ireland is undermined by men with troops, he finally says, “I am neuter” in a great Shakespearean pun.

There is a brief appearance, too, by Harry Percy (Matthew Needham), who will become known as Hotspur by Henry IV, Part 1 and is already clearly a man of action and sinew, albeit a bit dim.

Britton (right) with Sean Chapman as Northumberland. Photographs by Richard Termine.

Richard II is all verse, and is spoken commandingly here. Tennant raises the pitch of his voice as the lightweight king. His delivery of “For God’s sake, let us sit upon the ground/And tell sad stories of the death of kings” is beautifully staged—his dwindled retinue all sit, although it’s clear their butts are unfamiliar with the Earth. When Richard then takes off his crown and contemplates it, the parallel of Hamlet looking at Yorick’s skull is unmistakable. (Some critics viewed Tennant’s Hamlet in 2008 as the best since Laurence Olivier’s; this New York debut is mandatory for anyone who regrets missing that.) The crown itself is used again when Tennant spars wittily and cleverly with Bolingbroke. He takes it off and holds it out to his side. “Seize the crown,” Richard tells Bolingbroke, and then, in the tone of coaxing a dog to fetch, “Heee-re, cousin.”

With the language on display, the primary feature of Stephen Brimson Lewis's set is a catwalk that descends at times for Richard’s court appearances; projections, including a white stag and a bloody moon, add color. Trios of trumpeters and plainsong singers in the side balconies provide considerable aural texture, while the smell of incense is an unexpected addition of medieval atmosphere along with Tim Mitchell’s tenebrous lighting.

Any quibbles are minor. Occasionally a character lowers a voice and a word or phrase is dropped. Leigh Quinn’s Queen is passionate and speaks clearly, but one wishes her power of projection were as strong as her acting.

Overall, though, Doran has created this 14th-century Shakespearean world with great precision, attending not just to Tennant’s towering performance, but to tiny moments: the forgetfulness of Jane Lapotaire’s Duchess of Gloucester, the dry joke cracked by a lady-in-waiting and the chilling prophesies from a minor character: “The pale-faced moon looks bloody on the earth/And lean-looked prophets whisper fearful change.” This Richard II is curtain-raiser to what promises to be a landmark visit.

The Royal Shakespeare Company’s Richard II plays in repertory with Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2, and Henry V, through April 21 at BAM Harvey Theater (30 Lafayette Ave. between Ashland Place and St. Felix Street in Brooklyn) through April 29. Tickets start at $35 and are currently on standby for this performance. Visit www.bam.org/theater/2016/richard-ii for information on availability or the day-ticket lottery.

Crossing Into Madness

The filth, danger and enchantment of the South comes alive in Adam Rapp’s Wolf in the River and it all takes place around a fresh mound of earth with intoxicating purple flowers. The Man (Jack Ellis) is a shapechanger and he stands barefoot in the dirt, like he is on a soapbox, and counts each audience member one at a time. He is shirtless and holds his torso firmly as he moves around the room demonstrating his dominance. The shapechanger can supernaturally change from a man, to a wolf, and to a nasty, old woman named Dumptruck Lorna. The Wolf smells a pair of used panties from a canvas sack and examines a muddy sundress, cutoff jean shorts, sneakers and a cell phone. Ghoulish men and women known as the Lost Choir creep around the space and hide in the shadows. Suddenly, a distraught, young woman, Tana Weed (Kate Thulin), runs onto the stage naked, grabs the items and is attacked by the Wolf and Lost Choir.

The production explores Tana’s relationship with her apparent first love, Debo (Maki Borden)—a jovial young man from Benton, Illinois. Lighting designer Masha Tsimring uses the warm light from a worn fridge skillfully to create intimacy as Tana and Debo talk to each other over the phone. Scenic designer Arnulfo Maldonado constructs a psychotic background with black stick figures drawn across plywood walls and a thick rope looming over the stage. On a back wall hangs a picture of Jesus Christ with a green, plastic Christmas garland and red bow.

Tana also experiences a contrasting world of chaos and violence that is ran by Monty Mae Maloney (Xanthe Paige). Monty is a blood collector and uses a cane with an alligator head on top of it even though she walks perfectly well. She is also the girlfriend of Tana’s older brother, Dothan (William Apps). Dothan is a dishonorably discharged veteran who spends his time silently tinkering with electronic gadgets. Monty’s gang consists of Aikin (Karen Eilbacher) and Ansel Pinwood (Mike Swift), who goes by Pin. Aikin appears to be a masculine lesbian and eats the purple flowers to get high. Pin runs onto the stage half-naked with a printed copy of Miley Cyrus’ face taped to a blow-up doll. He has sex with the doll over the mound of dirt. Monty ensures that her crew have their intravenous medical ports working properly so that she can draw blood from them.

Theatergoers experience Tana’s worlds as though they are sitting right next to her, and this intimacy is the real value of this production. When Monty slams Tana’s head into the fridge, audience members might even get fake blood splattered on their clothes. The fresh soil from the center mound of earth and burning incense also brings a sense of smell to these worlds. Tana’s life is exposed, criticized and objectified. Nothing, including Tana’s virginity, is not left unjudged. Under Rapp’s direction, The Flea Theater’s resident volunteer acting company, The Bats, have these worlds come alive in raw form.

Rapp and the cast make bold choices and commit to them, but the challenge is having these choices payoff with theatergoers. The vulgarity in some of the scenes can create distance for theatergoers who are trying to relate to the characters and understand the storyline. It is awkward watching the Wolf engage with audience members when the audience is still just trying to figure out what is going on. The overall aim and vision can be unclear and other markets may not respond to this material.

At the same time there is so much depth to these characters that each of them could have their own play written about them. The issues are rooted more so in the characters and not the plot. Each character’s stand is like figments of Tana’s imagination. The violence, nudity and sexual situations do effectively show the characters’ vulnerability, desperation and fears–even when theatergoers have already seen enough.

Wolf in the River is recommended for theatergoers who want to be challenged and still have the patience to see what this production has to offer at the end. It is not recommended for those seeking a nicely woven and easy-to-swallow story. Thulin’s performance as Tana is solid and her ability to stay in character and be innocent while going through hell is very impressive. Tana’s hunched shoulders and bloody nose suggests that she is timid and defeated, but her determination to leave her hometown and run away with Debo stays present in her eyes. She is not a victim, but a survivor who hides her reality from Debo. The audience is the river and the Wolf says, “You go for miles and your current’s so strong this time a year that the people in this town string ropes across to help folks get to the other side.”

Wolf in the River runs until June 6 at The Flea Theater (41 White St. between Church Street and Broadway) in Manhattan. Evening performances are Monday and Thursday-Saturday at 7 p.m. and select matinee performances are Saturday at 1 p.m. and Sunday at 3 p.m. Tickets range from $20-$100. To purchase tickets, call 212-352-3101 or visit TheFlea.org.

Shards of Light

How many times has someone attempted to explain the "situation" in the Middle East? And, of those times, how many have felt one-sided? No matter how hard the best of us try, the reasoning often has a bent, a leaning toward one side or another. “It’s complicated,” after all. In Wrestling Jerusalem, Aaron Davidman presents 17 voices of men, women, Israelis, Palestinians, Brits, doctors, farmers, and rabbis, among others, in a manner that can be heard and understood with refreshing deference. His affinity for the material, as well as the struggle and heartbreak of people, is breathtaking.

As the playwright, Davidman has done his homework. “You might say it all started in 1948” or “You might go back to World War I,” he says, but wherever you might think he is leading you, it’s not where he’s going. Wrestling Jerusalem is in uncharted territory. Six Day War, Intifada, United Nations Resolution 181, Invasion of Lebanon, or the settlements: he unwraps the causes and the concerns, the politicians and the terror attacks with such deftness that he draws the audience into being concerned regardless of any predilection they had when they walked in. He causes one to care, to want to know more. “If, if, if, if, if, if,” he declares. If only this hadn’t happened or if that hadn’t occurred, things would be different, right? It’s the manner in which he constructs the inquiry that is at heart of his invitation to look deeper, practically challenging the audience not to care.

Davidman’s skill reaches well beyond his writing. His talent as an actor, adept at the nuance and complexities of characterization, is thoroughly engaging. Each of the 17 is based on people he has encountered in his attempt to understand the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, whether in North America or on his travels through Israel and Palestine. Like a chameleon he embodies the subtleties of Farah, a Palestinian woman in her 30s, or Professor Horowitz, a British man in his 50s, or Rabbi Moses, an American in his 60s. Davidman sings Yiddish songs from his days at children’s camp to the cherished “Shalom Aleichem.” He dances to folk songs from the homeland as Allen Willner’s lighting creates shadows around him. It is equally as powerful to observe him on the ground pushing invisible sand, as it is to viscerally feel his fear crossing the Israeli border into Palestine; he is that passionate.

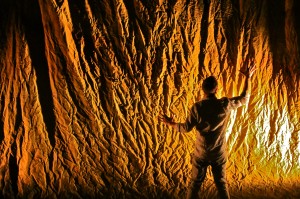

The backdrop for this extraordinary experience is a beautiful, yet simple painted tarp along the back wall designed by Nephelie Andonyadis. At times it has the feeling of windswept sand and at others a ragged mountain range, depending on the lighting of Willner who colors the backdrop and space with rich oranges and yellows, or a vibrant blue, and then in an instant throws Davidman into the harsh, bright sunlight of the Ben Gurion tarmac. Bruno Louchouarn is responsible for original music and haunting sound effects. Credit for the keen direction of Wrestling Jerusalem goes to Cuban playwright and director Michael John Garcés. He brings a rich and varied background in community-focused plays, which is particularly evident in this production.

There are many profound and wrenching moments in the 90-minute Wrestling Jerusalem. Davidman’s character, Ibrahim, a Palestinian cries, “The only Israelis my children have known drive tanks, invade neighborhoods, intimidate their parents at checkpoints. The only Israelis I have known own the water trucks that deliver my water. My water.” His interaction with Rabbi Moses, who emphatically declares, “Adonai Echad does not mean there is only one God. Adoni Echad means God is One. What’s the difference? There’s a huge difference. God is One. One, not the number. One, the truth of indivisibility.”

All of which is extremely important in a landscape where people, politicians, and religion drive the conversation as to “who does the Holy Land belong to?”

“As the muezzin’s call to prayer floats out over the Wall,” Davidman tries to make sense of it all. “Please. You can hear the cry inside the cracks. Please, God, help me. Help us. The Wailing Wall holds the tears of generations.” His inquiry into the Middle East conflict may not answer any questions or even the ones everyone has come to expect, however he wrestles the word humanity into the bright light of day. “’And it’s the work of human beings,’” say the Kabbalists, “’to find those sparks, those fragments of goodness, and put them back together. It’s how we heal the world, they say.’”

Wrestling Jerusalem runs through April 17 at the 59E59 Theaters (59th between Madison and Park Avenues) in Manhattan. Evening performances are Tuesday through Thursday at 7:15 p.m. and Friday and Saturday at 8:15 p.m. Matinees are Sunday at 3:15 p.m. There is no late seating. Tickets cost $35. To purchase tickets, go to 59e59.org or visit TicketCentral.com.

Air Pump Wheezes

Anne Washburn’s perplexing Antlia Pneumatica takes its name from a constellation. In the 1750s, French astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille “pulled together leftover stars and made new constellations,” explains Adrian, a visitor to a remote Texas home. The astronomer named one of the constellations he created “the air pump,” known by its Latin name as Antlia Pneumatica. It’s one of the few fascinating points in Washburn’s meandering play.

Subtitled “a play about place, space, grace,” Antlia Pneumatica is structured as a collection of scenes around a kitchen island, monologues, stories, recitations and audio conversations. Most of the latter involve Nina’s two children, who are 5 and 7, but there is a scene of a nighttime encounter of two of the adults that proves a red herring. During these voice-overs, for seemingly interminable stretches, the stage is dark. Although a note from the playwright extols the art of listening to rather than seeing a play, the scenes come off as a torturous radio show and may spur you to cancel your subscription to NPR.

Insofar as Washburn’s title has any parallel to the action, it seems to be that she has used bits and pieces and leftovers as the meat of her story, in the same way that Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille collected unused stars for his constellations.

The deceased friend is named Sean, and he lived in New York; most of the characters had lost touch with him following his downward spiral into alcoholism. Much is made of who is coming for the scattering of Sean’s ashes, and a viewer has to listen closely to realize that, as the play progresses, other characters have arrived besides the ones who are on stage. New cars belonging to new names are parked in the driveway.

The conversations seem deliberately mundane and opaque, and although director Ken Rus Schmoll imparts a certain sporadic charge to them, and there’s a sense that the characters know one another so well they use shorthand to communicate, the effect is frequently to leave the listener at a loss.

When Len arrives carrying the ashes of Sean (earlier the character who was picking them up was a woman, but who knows what happened to her?), there’s talk about where to scatter him, and Nina even suggests baking a teaspoon into food they’d consume. This plot twist is not only unpalatable, but it has been done to death: the mistreatment of cremated remains in the theater is a Ph.D. thesis waiting to happen.

Late in the play, a friend named Bama arrives, and Crystal Finn brings an espresso shot of energy to the lethargic proceedings as a fast-talking Southern charmer. (Finn appears earlier in a scene with the others, all standing at the forestage and speaking directly to the audience; there’s no effort to explain who her character is or why she’s there and then disappears until the end.) A recollection from Bama sparks a story from Len that ends the drama on a supernatural note. The cast sings a song as the play peters out.

Washburn has a following and her work is produced regularly, but she also has skeptics. Obscure and unsatisfying, Antlia Pneumatica will give the latter plenty of reason to carp.

Anne Washburn’s Antlia Pneumatica runs through April 24 at Playwrights Horizons (416 W. 42nd St. between 9th and 10th Aves. in Manhattan). Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. on Wednesday-Saturday and at 7 p.m. on Sunday; matinees are at 2 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. For tickets, call Ticket Central at 212-279-4200 or visit TicketCentral.com.

Q&A: Stronach’s Choreography Drives ‘Light, A Dark Comedy’

Tami Stronach began her career playing the Childlike Empress in The NeverEnding Story (1984). However, she followed the screen credit by pursuing dance. While dancing full-time on her toes, she started to miss theater so her next move brought her back. Fortunately, acting chops didn’t have to suffer the lift her high step always gave her. As part of Flying Machine with several friends, this company approached theater though movement, and for seven years, she stayed connected to both disciplines before folding. But the members eventually realized they missed each other, and coalesced movement around providing high quality theater for families. The formation of Paper Canoe would coincide with a New Victory Theater LabWorks program seeking plays for children and resulted in a production that “sucks the light out of the theater,” according to Stronach, who choreographed the play and stars as the lead character Moth. OffOffOnline: So does Light, A Dark Comedy have everyone in the dark, bumping into each other?

Stronach: No, the play is well lit. The audience can see everything. It’s the language of the play. But the premise is the sun has been stolen and forgotten. We’re trying to show how quickly history can vanish, and the importance of keeping stories alive.

OffOffOnline: Who stole the sun and why?

Q&A: Stronach’s Choreography Drives ‘Light, A Dark Comedy’

Stronach: The world was constantly lit and everybody worked all the time. This meant everything was go-go-go, and people never saw their children. At the same time, the space for reflection and dreaming got sucked up into this constant, bright, manic whirlwind. So an inventor tried to bring balance by creating a dark maker and ended up stealing the sun. The world was left in the dark, and Moth, my character, is trying to bring it back.

OffOffOnline: Where did this idea come from?

Stronach:We were brainstorming, and our director (Adrienne Kapstein) just said, “what if we created a world where there was no light.” We decided that was near impossible. But the impossibility intrigued us. Then Greg Steinbruner, Robert Ross Parker and I went on a writer’s retreat. We covered the wall with Post-it Notes and came up with the first two acts. But eventually Greg made revisions and completed the end. On the other hand, this is physical theater. So the story was written as we improvised things in rehearsal. We would then go home, and write what they saw. So the relationship between image and text was very organic and fluid. This amounted to a play written by a choreographer, a writer and a physical theater artist—providing all these different entry ways into the drama. Then last year Greg Steinbruner rebuilt the script into what it is now with the help of dramaturge Jeremy Stoller. Ultimately our goal as a company is to produce work that is as rich in narrative and text as it is invested in creating visual poetry.

OffOffOnline: Can you describe this world a little more?

Stronach: The actors wore a headgear called dim makers, which helps them see, and the city functions on a grid of hooks and ropes so people don’t get lost. It’s sort of like the trolley system in San Francisco. But acts as a metaphor for staying inside the box and not questioning the way things are. As a result, adults might contract “the sleep,” where they enter into a dream state and never come out.

OffOffOnline: How does Moth figure into all this?

Stronach: She unplugs from the grid, and goes off into the darkness where she meets a boy who has lived his whole life alone. Figuring out all these genius mechanisms for surviving, they then meet Sunny and Ray who have created a clandestine radio show. From their platform, the duo pretends to be on a beach and have gone into complete fantasy to deal with the problem. So they sit around and pontificated about the sun without doing anything about it. But the idea is to have characters with flaws and together there’s enough inertia and alchemy to achieve the things that shift society.

OffOffOnline: The play is billed as a little scary? Do parents have to worry?

Stronach: Well, it’s a mix. There’s a lot of humor, but I think losing your mom in a black void would be scary for a 4-year old. An 8-year old, on the other hand, should be fine and doesn’t mind being a little scared—especially since we have a happy ending.

OffOffOnline: What was the challenge of writing for children and adults?

Stronach: People underestimate the intellect of kids. They come into the theater with fewer assumptions and are more willing to be carried away by the story. So the story can reach audiences of all ages.

OffOffOnline: Finally, what message are you conveying about breaking free from your parents’ worldview?

Stronach: Moth doesn’t accept the gloomy truth she’s supposed to accept, and she changes the world. So I want my daughter to believe that she has the strength to find solutions that my generation didn’t think of.

Read Ray Morgovan's review of Light, A Dark Comedy here.

Light, A Dark Comedy runs until April 10 at the Triskelion Arts Muriel Schulman Theater (106 Calyer St. between Clifford Pl. and Banker St.) in Brooklyn. Matinee performances are Saturday and Sunday at 10:30 a.m. Tickets cost $18. To purchase tickets, visit www.papercanoecompany.com.

The Opposite of Light

Light, A Dark Comedy is a clever and smartly written play wrapped neatly with an amazing array of costumes, puppetry, lighting and media. It delivers a futuristic world ruled by an evil mayor and her equally evil, if somewhat “pretentious mystical nitwit,” sister. Sunlight has been literally sucked from the sky and leaving everyone to "stay online" or fall into darkness. No one really remembers actually seeing the sun, however, there are references and ditties scattered throughout the play that alludes to the sun. So much so that the words "day" and "light" have been replaced with the word "dim." What happens to the human spirit when subjugated by darkness and despair? And, for a young girl–what will she resort to for extra rations for her and her mother?

While pulling from modern mythology, movies and history, Light, A Dark Comedy is rich with symbolism making for an ominous, expressive tale for a modern age by playwright Greg Steinbruner. The story follows a young girl called Moth on a journey through her own darkness, from completely believing the evil Mayor to eventually confronting the truth and the Sandman. Along the way, Moth, played by Tami Stronach, encounters the Sleeper Services, who take away those who have fallen asleep. Moth also comes across the evil Mushanto Mushroom Corporation–where orphans are conscripted to work off their debt to pay for the care of the sleepers, The Underground–a rag tag group making up the resistance movement, the Queen–whose whispers cause people to sleep so that she can control their dreams, and finally Sunny and Ray–who broadcast an illegal radio show with supposedly cryptic messages for The Underground. The story languishes in the middle and it might be a tough sell for children due to the length and heavy subject matter. However, the detail in the story woven by Steinbruner and the tightly choreographed production is incredibly engaging.

Light, A Dark Comedy is brought to life by a great cast who, with the exception of Stronach, play multiple roles while creating and re-creating the stage for each scene. Here, darkness and shadows allow for characters to blend in while holding up a screen to complete the set or make a large flock of birds swirl overhead. Stronach, similar to Judy Garland in the Wizard of Oz, is the thread throughout this 90-minute journey and is rarely off stage. She, as well as the entire cast, is completely immersed in her character, movement and the story. Everything is so tightly intertwined to bring anything less to the stage could easily be catastrophic. Carine Montbertand plays the evil Mayor with great aplomb delivering a wicked, sinister character. It is her portrayal of the Mayor’s sister, The Queen, though, that appears forced. It is almost as if she is trying too hard to make her character uniquely different than the Mayor. Steinbruner's play challenges six actors, including himself, to play 16 roles in one production. With the extraordinary direction of Adrienne Kapstein the cast utilizes every opportunity to nuance 16 characters to life. From language and dialect to physical attributes and an abundance of costuming this is a challenging play both physically and mentally, and the cast made it appear seamless under her guidance. It is quite surprising when only seven actors appear on stage at curtain call.

Before all of this could take place, a talented development team created a very complex and moving production. Barbara Samuels delivers unique lighting to a relatively sunless play, Theresa Squire layers costumes for 16 characters to change into quickly, Mark Van Hare designs subtle sounds and striking music, Tom Lee designs vivid projection imagery, and Lake Simmons' delightful puppetry includes an expressive chicken laying an egg and a giant dragonfly who buzzes about the characters. Tying the vivid production together is Deb O with a steampunk style set design that utilizes three rolling “stages” and holds a multitude of props to create scene upon scene.

Light, A Dark Comedy is an unexpected 90 minutes that touches each of the five senses and is an invitation to explore the sixth. As Moth describes, “It’s on the tip of your tongue, but the name of the thing–the thing that’s missing–just doesn’t come to your lips.” It’s when Moth ventures out into the world and she comes to the crossroad of curiosity and dreaming, that she understands that only light can overcome darkness.

Light, A Dark Comedy runs until April 10 at the Triskelion Arts Muriel Schulman Theater (106 Calyer St. between Clifford Pl. and Banker St.) in Brooklyn. Evening performances are March 25 at 7:30 p.m. and matinee performances are Saturday and Sunday at 10:30 a.m. Tickets cost $18.00. To purchase tickets, visit papercanoecompany.com.

On Puppets, Music and Race

In standing publicly and personally for the contribution of black spirituals and melodies to the future of American music, 19th-century European composer Antonín Dvorák took up arms against a sea of racism that did not subside with the ending of the Civil War. The New World Symphony: Dvorák in America, produced by the storied Czechoslovak-American Marionette Theatre, uses the little-known visit of the composer to our shores only 27 years after the Civil War to take a bold, bracing and exuberant swipe at American racism of the past and its echoes up through our current presidential elections. The production, which combines puppets with human actors, is nothing if not wildly imaginative and, at the same time, deeply serious and grounded in the historical record of Dvorák’s sojourn in the United States. Written and brilliantly directed by Vit Horejs, it is playing at the La Mama Experimental Theatre Club.

From 1893-95 the unassuming, prolific and famous Dvorák was the director of the National Conservatory of Music of America, based in New York, a brainchild of the philanthropist Jeanette Meyers Thurber. A woman far ahead of her time, Thurber sought out musical talent among “female, minority, and physically disabled” students, and in 1893—at the height of Jim Crow and of lynchings across the South—she and Dvorák initiated a tuition-free policy for black students. It was during his residency as director of the school that Dvorák composed arguably his finest and most beloved work, the New World Symphony. Among other pieces written in his “American” period, it was music influenced by the “Negro melodies” Dvorák so deeply admired.

At one point Dvorák remarks that “the future music of this country … must be founded upon what are called the Negro melodies. This must be the real foundation of any serious and original school of composition to be developed in the United States.” The statement, like many of the lines in the play, is drawn verbatim from writings by and interviews of Dvorák and contemporaries. While Dvorák’s prescient vision of the development of an American musical idiom within a deeply hostile and racist context is the overpowering theme of the play, the lively portrait of the period, wrapped, as it were, in the candy of broken violin parts, puppets, and theatrical slapstick, includes Prohibition, labor unrest, Tammany Hall, the Haymarket Riots and, importantly, the Columbian World Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893, in which the black Paul Lawrence Dunbar makes his appearance.

Horejs’s production includes both period and modern costumes at the same time that a fair number of lines of its text also wander from their strict historical period, as when Nazi Reichsminister Josef Goebbels says: “If by jazz we mean Judeo-Negroid music that is based on rhythm and entirely ignores melody, why then we can only keep the lower race responsible….” Another voice later declares, “I am now calling for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.” The connections between racism old and new, and, in fact, Old World and New World, could not be clearer.

In the play, as in life, we see Dvorák take black and Native American talent under his wing: Harry Burleigh and Will Marion Cook, black musicians and teachers who would deeply influence their students and the development of black musical forms, are two who appear in the play. Chief Big Moon from the Hunkpapa Tribe is another student of Dvorák who impressively lectures on arcane language issues on stage. The play ends with music that sweeps from gospel to jazz and to rock. Surely Dvorák’s prognostications about the black musical genius and its centrality for American music proved accurate.

As a composer known for bringing folk themes from his native Bohemia into his music, Dvorák would surely have been pleased to have his life rendered in the theater tradition of puppetry so dear to the hearts of Czechs. Ben Watts made for a Dvorák of boundless energy and verve. The rest of the cast was terrific.

In organizing the script in Dvorák’s actual footsteps rather than around a conflict or obstacle faced by the composer, Horejs perhaps sacrifices dramatic power for his historical purpose. No matter. The fun and slapstick of the production itself, its underlying serious ideas, and the concert quality of the music made up for any weaknesses. James Brandon Lewis on sax, Luke Stewart on bass and Warren Trae Crudup III on drums were simply outstanding. Harlem Lafayette, who played the black musician Harry Burleigh, has the voice of an angel, as does Valois Mickies who played a black female singer. Original music not composed by Dvorák, was composed by James Brandon Lewis.

The Czechoslovak-American Marionette Theatre production of The New World Symphony: Dvorák in America runs through March 27 at the La Mama Experimental Theater Club, 66 East 4th St. Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Thursday through Saturday; matinees are Sundays at 4 p.m. Tickets are $25. Seniors and students are $20. Ten $10 tickets are available for every performance on a first-come, first -served basis. For tickets, call the box office at 646-430-5374 or visit www.czechmarionettes.org.

A Game of Treachery

Letter of Marque Theater Company’s Double Falsehood is a tight and neat production of a play credited to William Shakespeare and John Fletcher, and adapted for the 18th-century stage by editor Lewis Theobold. There is some debate whether Shakespeare actually wrote this play, but director Andrew Bothwick-Leslie, in program notes, suggests that audiences put that aside and enjoy the ride through this “wild and unnerving story.”

Double Falsehood is a story of betrayal, forced marriage, rape and reconciliation. Duke Angelo, played by Nolan Kennedy, has two sons. Roderick (Welland H. Scripps) is upstanding, while the other, Henriquez (Adam Huff) is a hooligan. Henriquez causes a lot of trouble for everyone because he can’t keep his desires for women who don’t want him to himself. First, he rapes Violante, played by the wonderfully physical Poppy Liu. At one point, when she is overcome with disgust after Henriquez’s violation, she rubs and hits her body as if she could physically rid herself of the experience.

Next, Henriquez insists on marrying Leonora (Montana Lampert Hoover), his friend Julio’s (played by Zach Libresco) love interest. He does it because he can. After all, he is a nobleman, which trumps Julio’s power. Not only that, Leonora’s father, Don Bernardo, played with weight and depth by Ariel Estrada, is so hungry to align himself with the Duke’s wealth that he forces the marriage to take place even though Leonora refuses. Like King Lear, Don Bernardo is full of hubris and self-import. And also like Lear he is humbled in the end, but not before he bellows in rage at his daughter to make sure she marries Henriquez.

As the enfant terrible, Huff does an excellent job and resembles a young Johnny Rotten with his shaggy light-blond hair, which he spikes at times or slicks down at others. His nimble, earthy walk and demeanor give him the charm of a snake making its way slowly toward its prey. Unfortunately, all in his path are hurt by his actions, and he shows no compassion or remorse. He feels perfectly entitled to get what he wants.

The costumes, by Claire Townsend, are an intriguing mix of metaphors, and emphasize the quality of the characters well. Some wore more traditional-looking Elizabethan garb while others, such as Julio and Henriquez, wore contemporary clothing. Henriquez’s costume, in particular—red sneakers, a red hoodie, and a long black coat with gold embroidery on the front—made him look like a hipster straight out of Williamsburg and heightened his “I don’t care what anyone thinks” mentality.

One of the best scenes that Bothwick-Leslie stages is a simulated horseback ride through the woods by Scarlet Maressa Rivera, who plays a citizen, and Gerald, a messenger of sorts. Rivera “rides” through the woods as other cast members run past her with tree branches and a drum beats to indicate horse’s hooves. It’s a wonderful and original idea that is twice as enjoyable the second time. Nolan Kennedy, who plays the Duke, is also the music director, and the lovely musical scenes including a trio singing about death and love, accompanied by Kennedy on the ukulele.

The company did a good job of using the Irondale Center playing area in a beautiful old church. The space has been rendered wide open (no pews or built-in stage, etc.). It can’t be transformed into a black box, but the company utilized rolling panels and a small platform, conceived and designed by Steven Brenman, to create a smaller performance space. At times, the panels were removed to show a wider space, or more distance between places. In Elizabeth theater, time and space were indicated through language, but these small visual indicators helped orient the viewer, especially at the end when there was little movement and a lot of dialogue.

Luckily, all’s well that ends well, in the manner of Nicholas Sparks’s romantic novel The Notebook. When Leonora and Julio are finally reunited at the end of the play, they run to each other and Julio scoops her up high into his arms. Cue the rain. It’s a soppy and romantic moment, but effective nonetheless. If it started out worse than real life, it ends better and, although Henriquez’s actions are particularly heinous, our faith in redemption and justice are restored.

Letter of Marque Theater Company’s production of Double Falsehood plays through April 9. Performances are at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday at the Irondale Center (85 S. Oxford St, Brooklyn). Subway directions: C train to Lafayette Avenue; B, D, M, N, Q, R, 2, 3, 4, 5 trains to Atlantic Avenue/Pacific Street; G train to Fulton Street. Tickets are $20; a limited number of tickets will be given away free to the public. To learn more, visit www.lomtheater.org.

Q&A: Fly Takes Off at the New Victory Theater

In 2008, as director Ricardo Khan was co-writing Fly with Trey Ellis, he made sure to be present as the Tuskegee Airmen were being honored at President Barack Obama’s inauguration. His realization was that the moment was set aside to recognize all the doors that these brave Americans opened. But for all the courage, perseverance and patriotism that propelled them, patience may have been the strength this corps of African-American fighter pilots needed most to see through their dream of making America a better place. OffOffOnline: What did they return to?

Khan: A country that seemed more racist than when they left. Rosa Parks, Jackie Robinson and the civil rights movement — it took a long time to fully see the tide turn.

OffOffOnline: How much of the story do you tell?

Khan: The training they undertook in Tuskegee, and dealing with the Jim Crow laws, segregation, and instructors and politicians who just did not want them to be there. But we begin and end the play with the inauguration.

OffOffOnline: How long has their story been part of you?

Khan: Since I was very young when I saw a picture of them that just fascinated me. The pride and the stance they were all taking — tall, well dressed and very proper like they were ready to change the world.

OffOffOnline: How is Fly different than other telling's of this story?

Khan: We have an interest in being able to tell the story of individual people so they’re not just figures in history. Then taking all the different personalities and egos, the play is about coming together as a team. That’s an important part of the way we did it. Because unlike television or movies, theater has a magical capacity to connect the actors to the audience to a point where you become a community. This hopefully leaves the audience walking out just a little better a person than when they walked in.

OffOffOnline: How do you show the strength of these men when it would have been easier to be resentful toward America?

Khan: This wasn’t a time when people were saying, "I don’t like my country." They were saying the opposite and wanted to be part of making a difference. Of course, they realized as bad as American racism was, fascism was worse. So they wanted to contribute, and believed if they could succeed, maybe one day racism could be toppled.

OffOffOnline: Tell me about the airmen (Brooks Brantley, Desmond Newsom, Omar Edwards and Terrell Wheeler), and the range of emotions they exhibit?

Khan: There is a huge range of emotions they represent — some are more filled with range, others with optimism. But at the same time, they’re young and in the army and not everything can be expressed. They’re also black, which means representing their race, and that adds to all the pressures to restrict their emotions. So we use an African and hip-hop rooted tap dance to convey the emotions that can’t be told in words.

OffOffOnline: How did you come up with this idea?

Khan: I wanted to find a way to grab the attention of a present-day audience so they weren’t just listening but were fully immersed. Tap ties to the '40s and hip-hop provides a hook to today so that it doesn’t feel like a history lesson.

OffOffOnline: How do you create action in the play?

Khan: We use video projections and tap to help create this world, but little props create the real action. All I have is four chairs and the airman’s trunks, and by manipulating them into different positions, the message comes across. So we might tilt a trunk up to symbolize a soda counter. The approach allows me to be as creative as I can to challenge the audience. As a result, the viewers are able to use their imagination to create a world in which we are not just feeding them information.

OffOffOnline: How hard is it to watch the play without being able to stop the action like in a film?

Khan: It’s extremely hard. But I’m doing another play in St. Louis so I’m going to preview the rehearsal today [March 1] and give my notes. Then I’m flying out, so in a way, I’m getting a reprieve.

OffOffOnline: Finally, what’s the message you hope people take away?

Khan: Don’t believe what you’re being fed about how different we are because of the color of your skin or if you’re a Republican or a Democrat. We are all in this together, and chapters in history like the Tuskegee Airmen, truly shows the ways in which we are the same outweigh the ways in which we are different.

Fly is running at the New Victory Theater (209 West 42nd St. between 7th and 8th Aves.) in Manhattan until March 27. Performance times vary. Tickets range from $15-$38 and can be purchased at http://www.newvictory.org/Show-Detail.aspx?ProductionId=6912.

Lost in Space

Real theater ignites our sense of moral duty and mirrors what is good and bad in our society. Writer Seanie Sugrue clearly does that in One Way to Pluto!, a seething reprimand of our irrational times. With humor and bite, Sugrue uses engaging dialogue to serve his thematic purpose: that we are fragile and easily broken in a brittle, capitalistic, greedy, political society that has lost its empathy. His characters’ rich dialogue stings in this punked-out philosophical commentary on our world.

Sugrue’s drama is reminiscent of the works of Sam Shepard, Harold Pinter, and Samuel Beckett. The playwright, who also directs, combines quick-witted moments with original music (by the downtown band Acquiesce) to create a CBGBs-style energy, earning its label of “punk theater.” With fine craftsmanship, Sugrue and his troupe, including designers, have memorably fused words and music together.

The story begins when Peter Cooper, a young musician struggling to find himself in New York City, wakes up to an escort, Tiffany (a sexy Jenni Halima), who demands money, and to Sean Dempsey, his irate Irish landlord, screaming for several months’ rent. Peter escapes the tougher realities of life as a poor artist, grappling with his sexuality by shooting up, dressing in drag, and running away.

Patrick Brian Scherrer gives a seismic performance as Peter, whose torment fits Sugrue’s dramatic response to the many serious issues of today. (The character performs a painful drug dance in drag that shows his inner turmoil.)

Sean (Myles O’Connor) as the ferocious landlord fed up with trying to help Peter espouses the playwright’s views with righteous indignation, spitting out lines like, “Everyone wants to die until they find out they’re going to.”

The Utah-born Tiffany, Peter’s paid-for one-night stand, offers him a no-nonsense perspective on life as she flits around disgusted at his living conditions—dirty and sparse. Social commentary on the city’s housing situation from the escort in ripped stockings really lends the piece a raw, punk edge.

Particularly fun to watch was Peter Halpin’s eccentric performance as Johnny, a “Billy Idol wannabe” Romeo who fires Peter from the band. Halpin’s kinetic, slithery movements were hilarious. Johnny changes persona with each new rock-and-roll fad, and Halpin’s ability to switch from Sid Vicious characterizations to a Rod Stewart “club” performance without forsaking the role of Johnny enhanced Sugrue’s insight into the superficiality of the gentrification of arts in New York City. Contrasting with the wilder moments is a scene when Peter steals from his mother, Molly: Mary Tierney conveys maternal anxiety and shows that an addict’s pain affects those who love him. And Courtney Torres plays a nerdy, college student, Charon, willowy and vulnerable and intruding on Peter’s homestead. Charon’s neurotic fluidity dances in step with Peter’s.

A minimalist set reflects the grit and grunge of the punk scene meshed with a Waiting for Godot motif and works brilliantly. Although manic chaos is on the surface of Peter’s struggle, the power of the play is in nothingness: the tone and mood of the set stand in juxtaposition to the thought-provoking dialogue.

A desperate Peter lands in Strawberry Fields, where he meets a homeless man named Dwight. In this whacked-out world, Dwight is the voice of wisdom, an “alchemist” in the urban desert. Played playfully and seamlessly by John Warren, he offers solid answers to the protagonist’s questions.

The most riveting scene occurs in a psychedelic trip to Pluto, where Peter and Dwight see all that is right and wrong in the world. Scherrer lets loose an inspiring rant about “planet of hate.” They ultimately conclude, as Dwight suspected, that John Lennon was right—“all you need is love.”

The play ends poignantly, with Dwight and Peter in their Central Park homestead, at peace with the world. The dramatic juxtaposition of Scherrer’s high-strung Peter with Warren’s mellow Dwight really captures the pathos of the final moment. While Sugrue berates the world for its hate-mongering, he also offers hope after so dark a journey.

Sugrue and Locked in the Attic, fellow producer Amanda Martin, and the historical 13th Street Repertory all have reputations for being politically bold in their presentations. This ensemble of artists inspires social awakening with an “in yer face” punch.

One Way to Pluto! ends tonight at 8 p.m. Tickets at $15 may be purchased at www.13thstreetrep.org or at onewaytopluto.brownpapertickets.com. More information about the jammin' soundtrack may be found at www.aquiesce.com.

Life Can Be Lethal

Compelling characters and complex questions about crime and punishment are at the heart of playwright Eduardo Ivan Lopez’s latest play, Natural Life, at the T. Schreiber Studio.

Like many of Lopez’s plays (Ribbon Creek, The Legend of Sam’s Point, Barth’s Dilemma), Natural Life draws inspiration from true stories and historical facts. Claire McGreely (Holly Heiser) has spent the majority of her adult life in prison, and now awaits execution for the murder of her husband, Virgil (Joseph D. Giardina).

In an effort to set the record straight before her death, Claire contacts network news anchorwoman Rita Hathaway (Anna Holbrook) and offers her an exclusive interview as well as the revelation that she is ending her quest for an appeal. Claire divulges to Rita that she wants to die.

But as Rita continues to speak with Claire and learns about her troubled past in flashbacks, the straight-shooting journalist’s preconceived notions about justice come into question. Jake Turner’s skilled direction keeps the action moving swiftly and clearly through the time jumps as Claire’s difficult childhood becomes achingly apparent. Sexually abused by her uncle from the age of 5, Claire was an alcoholic by age 11 and a prostitute by 14. The abuse continued when she married Virgil. Raised by her grandmother (Noelle McGrath), Claire received advice, she says, like “sex was all that men wanted. And if I was going to lie down with them, I should always get something in return.” It becomes clear that Claire is a victim as well as a killer.

Rita voices her growing belief that perhaps Claire doesn’t deserve to die to Gov. Ben Dushane (Bob Rogerson), with whom Claire’s fate ultimately lies. But the audience is confronted with the fact that a life in prison may be a more severe punishment for Claire, who explains, "My choice is death by slow deterioration or death by lethal injection, fast and, hopefully, painless. To die quickly or slowly … For all intents and purposes, my life is over."

Heiser’s portrayal of Claire McGreely is powerful and nuanced. She expertly crafts a character that has many sides and leaves no doubt that her case is not a simple one of black-and-white murder. Even more impressive is Holbrook, who creates an instantly likable and admirable character in Rita Hathaway. Her Rita looks as if she could star in a popular television series—impressively smart, driven, tactful and yet endearingly human.

The cast is rounded out by television station executive Dan Coleman (Don Carter) and prison guard Harris (Joseph Calderone). Carter provides the only comic relief throughout the play with his portrayal of a pompous, deceptive (“Well, technically, I guess I lied”) businessman with whom Hathaway must contend. The seven-person cast remains on stage throughout the performance, seated in a row of chairs behind the action, reminiscent of a jury—judging Claire’s every move.

Helping clarify the flashbacks are locations and dates of the action, displayed on screens built into the walls of an otherwise understated set by Pei-Wen Huang-Shea. The screens serve multiple purposes throughout the show thanks to sound and video design by Andy Evan Cohen. They don’t just set scenes but serve as prison surveillance cameras, office videogames for Coleman, and jail-cell television for Claire.

The intimate space, raw performances, and impressive script make for many emotional moments. The first act starts off grippingly at the climax of the story before circling back to show why Claire McGreely ended up pointing a gun at her husband.

Natural Life is thought-provoking and commanding. The subject matter is timely, and fans of recent pop-culture phenomena such as Making a Murderer, Serial and The Newsroom are likely to be riveted by this exploration of the justice system, the prison system, guilt and the media.

Natural Life plays at the T. Schreiber Studio for Theatre & Film (151 West 26th St., 7th Floor) through April 2. Tickets may be purchased for $20 general admission by calling the box office at 212-352-3101 or online at www.tschreiber.org. Evening performances are at 8 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. on March 23 and 30.

Secrets, Secrets Are No Fun

Stop for a second and think about the way in which one interacts with one’s family, the way one assimilates to one’s society, how one honors one’s ancestors, how one speaks one's truth, and most importantly, how one heals oneself. Familiar, written by Obie Award winner Danai Gurira, challenges its audiences to think of all these situations. However, it is also a play that one must watch in order to fully understand how it can be powerfully healing and a life-changing experience for the audience.

Directed by Rebecca Taichman, Familiar tells a story of a Zimbabwean family living in Minnesota. The eldest daughter, Tendi (Roslyn Ruff), is getting married in a matter of days, and her rehearsal dinner is in a matter of hours. As the family prepares for the rehearsal dinner, Tendi and her fiance Chris (Joby Earle) announce to the family that in addition to a traditional Christian wedding, they are including a Zimbabwean ritual. This unexpected turn causes secrets to be revealed, old wounds to reopen, and forces the family to speak the truths about the past.

Although not based on her life, Gurira draws upon her own experience to create a credible script. Similarities between her life and the script includes how her Zimbabwean family also moved to the U.S. and how she was raised in Iowa while the family in the play live in Minnesota. In addition, the script allows the actors to unapologetically speak Shona as she presumably also did in her household. Unlike other shows that often translates anything other than English, Familiar takes advantage of an opportunity to be authentic, as well as give any audience member who speak Shona a small taste of home.

The ensemble includes, the father Donald, played by Harold Surratt, who grounds each scene with subtle facial expressions and dialogue. Myra Lucretia Taylor as Anne, Tendi’s aunt, is a strong and demanding presence on stage that is the main person connecting the family back to Zimbabwe heritage and ancestors. Anne’s sister Margaret, played by Melanie Nicholls-King, is the glue that keeps the family under control, even when she might feel her own life is falling apart. A definite gem in the performance by being the character that continually handles her sisters Anne and Marvelous (Tamara Tunie), as well as continually attempting to keep everyone calm. Ito Aghayere as Tendi’s sister, Nyasha, whose relentless need to bring the family back to their traditions heals the family. Her energy and enthusiasm propels the play forward and brings it back to a nourishing place.

The ensemble's chemistry and impeccable timing is a tremendous success to the production. Ruff and Tunie exhibit the vulnerable bond between mother and daughter. To balance them out are the future family members, “white boy from Minnetonka,” Chris (Earle) and his brother Brad (Joe Tippett). Their natural comedic interactions add to the play and cause the audience to laugh and scream in enjoyment. Overall, it is the ensemble’s conversations and arguments that encourage open discussion about past family issues, current events and pushes the audience to question their own lives.

From any seat, the audience can see all aspects of the highly-detailed set designed by Clint Ramos. Marvelous’ and Donald’s house is two floors with hallways, real doors and family pictures lining the wall. It is a breathtaking set that anyone would want to live in, including the audience who sit in comfortably cushioned seats, as if sitting on individualized mini couches. To support this design, Obie Award winner and lighting designer Tyler Micoleau incorporates the lights into the structure of the set to allow it to seem natural. Even the window is lit so that it appears as if looking out on a snowy day in Minnesota.

Another noteworthy design element was the sound design by Tony Award winner Darron L. West. During intermission, the recordings of celebratory Mbira music by the Shona people of Zimbabwe filled the theater. With a very hectic and hilarious ending to Act One, the traditional music played during intermission is a great way to gently introduce the audience to Zimbabwean music, as well as connects with the Mbira that is presented by Nyasha during the performance.

Boy vs. Girl vs. Boy

The hot-button issue of gender identity is at the center of Anna Ziegler’s Boy, a troubling and moving new play, and the first world premiere from the Keen Company since 2008. The subject of sexuality is in the zeitgeist, from a new musical, Southern Comfort, about Georgia transsexuals, currently at the Public Theater, to civic debates about restroom accommodations.

The story that Ziegler presents falls on the serious side. During circumcision, one of a set of twins was horribly mutilated, losing his penis. His distraught parents write to a doctor who appeared on 60 Minutes and specializes in gender identity to seek help. He advises them to raise the infant, named Samuel, as a girl, Samantha.

Ziegler tells her story in flashback, starting at the moment Adam, who was born Samuel but raised as Samantha and reinvented himself as a man, meets a girl named Jenny (Rebecca Rittenhouse) at a Halloween party. Jenny is someone Samantha knew in school and shared a class with. Jenny doesn’t recognize Adam, for obvious reasons, but he feels a strong attraction to her.

Bobby Steggert invests Adam with a mixture of well-meaning sweetness and a tentative confidence that sometimes leads him astray. His initial meeting with Jenny goes awry when she confesses having a 4-year-old child and he says he likes children and would be glad to give the kid a lift. It puts Jenny on guard, but it’s symptomatic of Adam’s failure to fully socialize himself. And, without using makeup or drag, Steggert gently creates a little girl, crossing his ankles or pitching his voice slightly higher, or talking quickly, as children do. The plan of Sam’s parents, Doug and Trudy (Ted Köch and Heidi Armbruster), is to socialize him as a girl until he is old enough to have operations to create a vagina. But even with Dr. Wendell Barnes’s coaching, Sam feels innately more interest in bugs, cars, and traditional “boy” interests.

The play comes down strongly in favor of nature prevailing over nurture. That brings it in line with the idea that being gay or transgender is not some perversion of the natural order. Indeed, the perversion in Boy is clearly the mentality of Dr. Barnes (Paul Niebanck), the eminence who persuades Doug and Trudy to maneuver Sam into the opposite sex. Sandra Goldmark’s unremarkable furniture nonetheless provides a striking visual parallel to the psychology: second sets of furnishings hang upside down over the set, a visual parallel to Samantha's inversion.

Even misguided, Niebanck’s doctor is a touching figure, a self-possessed gay man (he calls himself “a former boy who didn’t quite fit in”) who means to do well and cares in his way for Sam. Yet Niebanck invests the doctor with a sense that he is perhaps too doctrinaire in his theories. A climactic scene when Adam confronts Dr. Barnes and reveals that he has become a man, thanks to operations, is quietly devastating for both characters.

Ziegler plots the course carefully, and under the direction of Linsay Firman, the flashbacks make sense and flow smoothly. As in the playwright’s last outing, A Delicate Ship, which took its title from a W.H. Auden poem, literature plays a part. Here, Dr. Barnes’s assertion that Paradise Lost is the greatest poem ever written hints at a concealed interest in playing God.

Serving as counterpoint is another poem, Leigh Hunt’s Rondeau, which Dr. Barnes introduced to Sam, that remains Adam’s favorite. Milton’s is highbrow and concerned with the ineffable; Hunt’s is quotidian and concerned with real life and the physical, and ends: “Say I’m weary/Say I’m sad/Say that health and wealth have missed me/Say I’m growing old, but add/Jenny kissed me.”

Every so often Ziegler indulges in sentimentality, notably in a late scene when Adam reveals the night his father told him about the accident. Eating ice cream in the car, Doug said: “You came out of your mother, just who you are. This kind, gentle boy.” Steggert smiles affectionately. “You shouldn’t drink so much, Dad,” he says helpfully. And the anguished Doug replies, “I know that. But sometimes we just can’t control what it is we do, can we?” When the story is done, Jenny wants to know what flavor the ice cream was. It’s a clumsy non sequitur suffused with cutesiness. But the errors are few. Even if you’ve thought you’ve heard all the arguments about the topic, Boy brings them home powerfully.

The Keen Company production of Boy runs through April 9 at the Clurman Theater (410 W. 42nd St. between 9th and 10th Aves.) in Manhattan. Evening performances are at 7 p.m. on Tuesday-Thursday and 8 p.m. on Friday and Saturday. Matinees are at 2 p.m. on Saturday and 3 p.m. on Sunday. Tickets are $62.50 and may be ordered at www.telecharge.com.

Whiskey Needs Respect

Eric Gilde’s new play the goodbye room focuses on a common experience in most everyone’s life—the death of a parent—but more important, it asks the question, “What’s left of the living?” There are those who have to handle the funeral arrangements, travel home for the service, or find a way to relate to one another during a time of grief. It’s the relating that most often gets in the way. Gilde has done an exemplary job of capturing the essence of this experience, and, as the director, creates the space for four talented actors to bring it to life.

It is a detailed re-creation that, without nuanced performances, could easily come off as flat. There is nothing new, there are no great surprises and no profound personal breakthroughs in the goodbye room. However, it’s the precise manner in which Gilde wrote the dialogue, directed the actors, and how they delivered it that enhances the drama.

Michael Selkirk plays the grieving Edgar, whose wife has just passed on. Edgar has two daughters—the “good,” overworked, overwhelmed daughter Maggie (Sarah Killough) and complicated Rebecca, affectionately referred to as Bex (Ellen Adair), who married and moved to Chicago five years ago. Bex laments not coming home sooner, while Maggie plays the busy martyr who stayed behind to work and take care of the parents. This sibling story has been told and retold following the death of a parent; however, it’s Gilde’s staccato dialogue, with the characters talking over one another, coupled with the generous space between the words, where the crux is to be found. Included in this drama is the affable family friend and former love interest Sebastian (Craig Wesley Divino.)

Bex is wound tightly, from the moment we hear the car door slam to when she finally tersely reveals, “Larry and I are getting divorced.” The estrangement from her family is exemplified by her awkward attempts to console her father or hug her sister. She often finds a way to make it more about herself than anyone else. Maggie, equally tense, lets on to anyone who will listen how busy and overwhelmed she is. Sebastian has found his second family and doesn’t want to let go, always being available to lend a helping hand. Edgar is trying desperately to understand this new void in his life, even while shuffling off to make coffee or trying make sure his girls are comfortable.

It’s when he shares his Irish whiskey with Sebastian that Selkirk delivers everything that resides just behind the dialogue. “I don’t think you should come around here for awhile,” he says, pausing for a moment, then saying, “Drink up.” The rage that seethes behind his full beard and scraggly appearance is subtle yet profound.

Justin Spurtz’s set covers every base, from the 1950s paint-by-numbers framed art on the wall to the collection of family photos and the paper plates complete with grease stains left behind by the pizza. There is the patterned family sofa that has lost its firmness over the years, and the coatrack filled with winter coats and scarves. Spurtz even includes a bit of whimsy with Bex’s childhood mug.

Jacob Subotnick layers on a sound design that complements each scene, from car doors closing to LPs with crooners on the vintage stereo turntable to the subtle patter of rain. The volume of the mobile-phone ring in the handbag was on point, and the iPod selection set the scene for the sisters to share too much wine, and finally themselves, is perfect.

Gilde’s drama touches slightly on the concept of the lingering spirit of the departed, with lights flickering or the broken stereo finally playing. It’s a welcome relief from the family drama being played out, but it’s also a hint that there is more to life than silly squabbles or playing the blame game one more time. Maybe love, as messy as it can be, transcends the boundaries of this reality to remind us of what’s important.

“The goodbye room” is at the Bridge Theatre at Shetler Studios (244 West 54th St., 12th floor) through March 19. Remaining performances are Wednesdays through Saturdays at 8 p.m. and Sundays at 3 p.m., plus Tuesday, March 15, at 8 p.m. Tickets are $15 and $18 and may be purchased by visiting Artful.ly.

Waterlogged Ethics

March 8th, 2016

Yes—there’s really a pool on stage at Red Speedo, the new play by Lucas Hnath (The Christians) at the New York Theatre Workshop through March 27. The pool is certainly an achievement for scenic designer Riccardo Hernandez, since it immediately places the audience in the natatorium where swimming stud Ray (Alex Breaux) awaits the following day’s Olympic trials.

But the lane of serene blue water that spans the forestage stands in stark contrast to the murky ethical dilemmas that Hnath examines. Ray’s future as an Olympic swimmer and Speedo-sponsored star are threatened by a dependence on performance-enhancing drugs; a brother whose financial well-being is inextricably tied to Ray’s success; an ex-girlfriend whom he desperately wants to marry; and a coach who is also looking for his piece of the glory.

Ray’s brother, Peter (Lucas Caleb Rooney), is a lawyer who yearns to quit his job and play full-time agent to his younger sibling. He’s willing to do whatever it takes to get his cut from the Speedo deal he has negotiated—even if it means turning a blind eye to Ray’s reliance on HCG—a synthetic testosterone classified as a performance-enhancing drug.

Ray’s ex-girlfriend Lydia (Zoë Winters) is bitter and angry after losing her license to practice sports psychology when she dabbled in the realm of pharmaceuticals. Peter helped get her convicted after speaking to the prosecution and relaying private information.

Ray’s coach (Peter Jay Fernandez) tries to take the ethical high road when he discovers what he believes are another swimmer’s drugs in his office refrigerator. But when he realizes they belong to his star pupil, he quickly changes his tune.

Then there’s Breaux as the athlete himself. The actor does a wonderful job portraying a character with more depth than meets the eye. Though Ray appears to be unintelligent and inept at grasping complex scenarios, it’s quickly evident that he’s not as dumb as he seems. Even his hideously large back and leg tattoo of a sea serpent is his own stroke of quasi-genius: “Just thought it would be good for publicity and stuff, because we all kinda look the same when we swim, because we all have goggles and swim caps, so I thought it would be a good idea to make myself really easy to spot, so like when I’m swimming, and they have the camera overhead watching us swim, it’s really easy to know which one I am, and everyone will be like ‘Whoa, who’s that guy with the sea serpent, he’s awesome.’” He is scared to fail and scared of what it will take to win, which results in his saying to Peter, Lydia and Coach exactly what each wants to hear—even if it isn’t true. But even though he’s a pawn in their endgames, he’s playing them too.

Director Lileana Blain-Cruz keeps Hnath’s script moving quickly, though the snappy, rapid-fire dialogue sometimes seems forced. It’s unclear if the choppiness is due to directing or acting choices. The script really soars when each character has a longer chance to speak—granting the audience a look inside their psyches. The air horn signifying changes in scene, however, does little to aid the audience, aside from causing them to jump.

For the most part, Rooney makes Peter deliciously deplorable. And while the rest of the cast hold their own, there’s nothing spectacular about their characters. What is spectacular is a climactic fight scene between Peter and Ray, choreographed by Thomas Schall, that takes full advantage of Hernandez’s set.

Hnath’s writing leaves no clear protagonist and offers no ethical calls throughout the 80-minute intermission-less production. Rather, he leaves the audience to ponder that all-too-gray area between right and wrong, good and bad.

Lucas Hnath’sRed Speedo plays through April 3 at the New York Theatre Workshop (79 East Fourth St.). Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Tuesday, Wednesday and Sunday; at 8 p.m. Thursday through Saturday. Matinees are Saturday and Sunday at 2 p.m. Tickets may be purchased by calling the box office at (212) 780-9037 or visiting nytw.org.

Young, Scrappy and Hungry

In the musky glory of The Kraine Theater, the March family spits crazy rhymes and self-professedly drops beats like a smooth silk ribbon. Although jaunty violins welcome us inside, it is the quick enticement of Lil' Theatre Company's hip-hop musical that soon settles us into our seats. Lindsay Taylor and Sara Stock are the writers of Lil' Women: A Rap Musical, which was inspired not just by Louisa May Alcott's novel but also by a certain popular rap musical that sends all who see it into fits of religious praise: Hamilton. The influence is too obvious to go unnoticed—sometimes to the production's occasional weakness. In an effort to reconcile the massive success of its progenitor with its own relative obscurity, Lil' Women drops hints of its inspiration while trying to break new ground with reasonable success.

Originally from the show streets of Orlando, Taylor's production is one of the more standout shows at this year's FRIGID NY festival—she is credited as the director and producer of Lil' Women. Its concept invites apprehension and interest in equal measure: taking a beloved classic and subverting its white, all-American tradition is no easy task. Many already know the story: Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy March weather crises of faith, friendship and love as they grow up under the benevolent eye of their parents, mischievous Laurie (the boy next door) and John Brooke (his tutor). It reads like a soapy, sweet tale, promising an uncomplicated ending. But somehow Taylor's hilarious spin on the March family makes it easy to forget the all too well-known plot, and enjoy the droll, nudge-nudge moments of musical inspiration that slips and slides from the pens of Taylor and Stock.